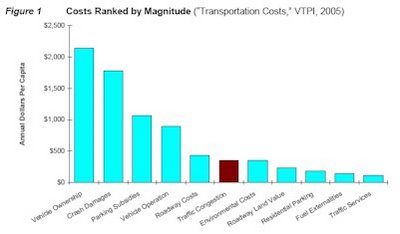

Business and political elites in Virginia are far more agitated about traffic congestion than average voters are, and they are far more willing to pay higher taxes to address it. Why is that? This chart, excerpted from “Smart Transportation Investments,” published by the Victoria Transport Policy Institute, provides important clues why.

This chart compares various costs, both personal and societal, of automobile travel. The report doesn’t say where this data comes from, so I don’t know how valid it is, but the larger point seems unassailable: Traffic congestion is a relatively small component of the total cost structure associated with automobile travel. When you compare the value of time, gasoline and engine wear-tear associated with congestion to the cost of buying a car, maintaining it, and paying for gasoline, insurance, crash damages and parking, congestion costs are almost trivial.

Of course, the chart provides average numbers. Congestion costs in places like Northern Virginia are significantly more acute than they are in, say, Roanoke. But even in Northern Virginia, the elites tend to be more upset than the Average Joe. Why is that?

Because the elites, by definition, have higher incomes and have more disposable income. They also tend to work harder, longer hours and place a higher value on their time. The Average Joe earning $25,000 to $50,000 a year has less money to spare to pay higher taxes but more spare time. While a member of the business/political elite might value his/her time at $100 to $200 per hour, Average Joe might value his time at $10 to $20 per hour. As a percentage of the total cost of car ownership/operation, the cost of congestion simply doesn’t loom as large for the little guy. But the cost of taxes does loom large because the little guy tends to be hard-pressed financially and less discretionary income to part with.

In sum, the little guy doesn’t like stewing in congestion. But he is more more likely to prefer paying the costs of congestion with his time rather than his taxes.

Of course, business elites are better organized than Average Joe — witness their recent proclamation in Northern Virginia in favor of more taxes for transportation — more vocal, more articulate and have more access to power. The voices of the elites carry much farther in Virginia’s political process than the voices of the little guys.

(Hat tip to Ray Hyde for bringing the VTPF study to my attention. Ray bears no responsibility whatsoever for the conclusions I have drawn in this post. But there’s more in the study to blog about, and I will make more posts in the future.)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.