by James A. Bacon

“Long haul” COVID is the term used to describe COVID symptoms that persist far beyond the normal four weeks of infection. It seems that Virginia schools are experiencing long-haul COVID, too: maladies that have arisen long after the impact of the original illness — the shutdown of in-person learning — has passed. Like long-haul COVID for people, long-haul COVID for schools often involves symptoms not seen previously.

School districts around the nation are canceling classes for what they call “mental health days” on the grounds that students and staff need breaks to handle the pressure of returning to school, reports the Wall Street Journal. More than a third of the 8,692 school closures reported this year have occurred in three states: North Carolina, Virginia, and Missouri.

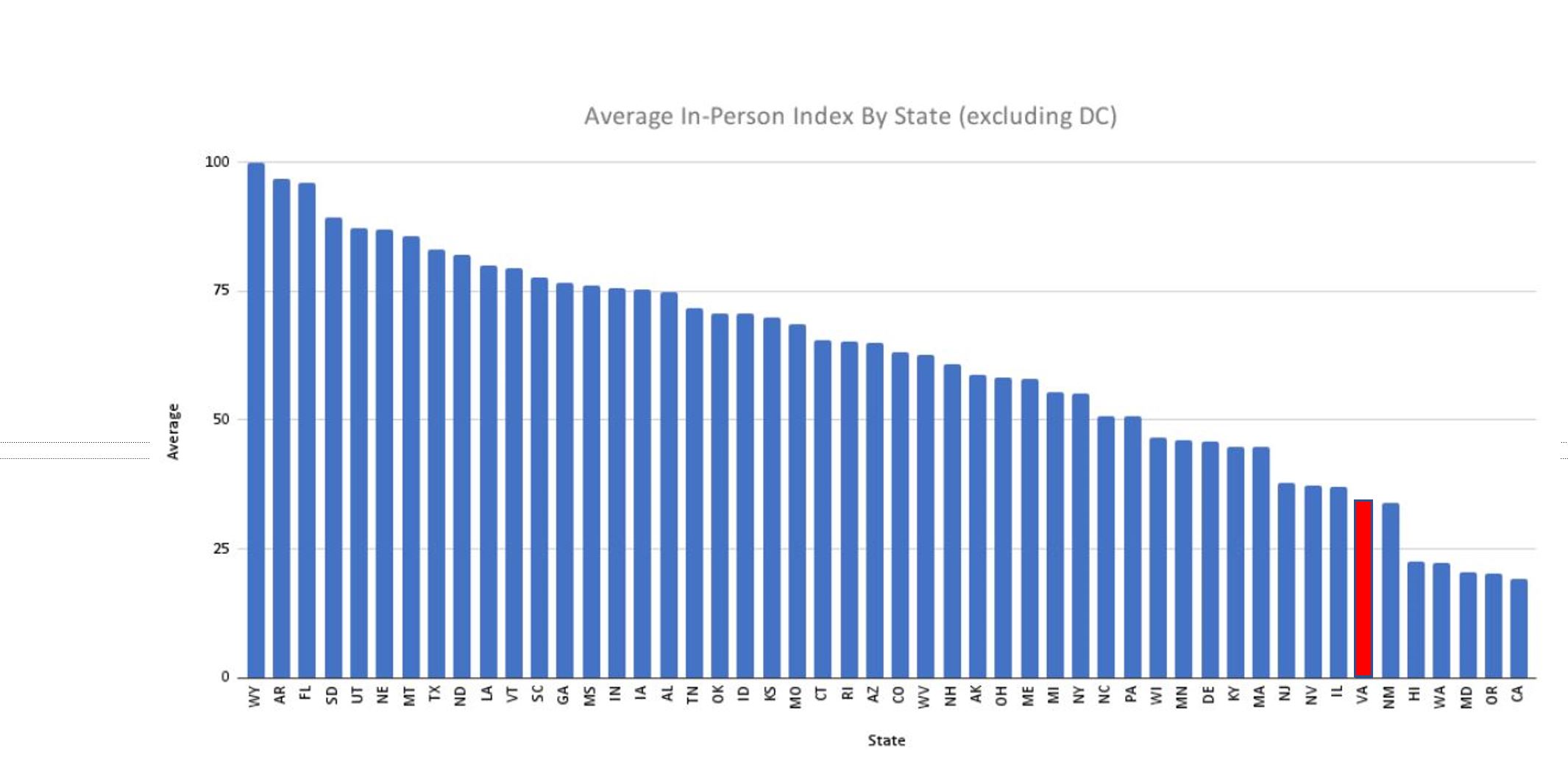

The Journal article specifically cites school systems in Suffolk, Chesapeake and Richmond. Teachers are experiencing burnout, and superintendents are giving them time off to recoup. In large part, the burnout is a consequence of the COVID-driven flight to distance learning in the 2020/21 school year. Virginia public schools had the 7th-lowest rate of in-person learning in the country, by one set of measures in the Burbio K-12 School Opening Tracker and 3rd lowest by another set.

Reagan Davis, president of the Chesapeake Education Association teachers union, told the WSJ that this school year is even more challenging than 2019/20, when schools abruptly went remote early in the pandemic and teachers toggled between virtual and in-person instruction. Davis, an eighth-grade teacher, said that this year he and his colleagues routinely work through 6 p.m. or 7 p.m. grading papers, catching up on administrative tasks because they have lost planning time while covering classes for absent teachers, and recording lessons for quarantined students.

The Journal also quotes Jonathan Young, vice chair of the Richmond school board. Students spent nearly 18 months at home over the previous two school years, Young said. Acknowledging the resulting collapse in standardized test scores, he says in retrospect that the decision to close in-school learning was not the right one. To help teachers cope this year, he would like the district to ease administrative requirements such as submitting daily lesson plans or attending professional development courses.

The Journal article has captured aspects of the problem, but there is much more to the story. So many Virginia public school children fell behind last year — more than 30% failed their English reading and 45% failed their math Standards of Learning exams — that administrators advanced everyone to the next grade with the expectation that teachers would work to catch them up this year. In other words, not only do teachers have the often-overwhelming challenges of a normal school year, they have to do remedial work with tens of thousands of students.

Alluded to only tangentially in the WSJ piece are the higher-than-normal teacher shortages that schools are experiencing. Staffing shortfalls have long been chronic in school districts with the most challenging students (those most prone to disruption and resistant to learning), but the situation is worse this year. As a consequence, administrators are adding extra classes to the workload of the remaining teachers. Additionally, the new social-justice approach to school discipline requires teachers to assume the roles of counselors and social workers for troubled kids whom schools can no longer suspend. Add to that the mandatory teacher “training” on diversity-equity-and-inclusion issues.

So, yes, many teachers are overwhelmed; they are burned out, and hundreds of them across Virginia are on the verge of quitting. And, as is all too often the case, teachers are most burned out in schools with poor minority students who have fallen farthest behind in their learning, are most disrespectful (and occasionally violent) toward teachers, and create the most disruption in classrooms.

Calling the days off “mental health days” makes it sound as if teachers are delicate flowers with frail, anxiety-prone psyches. Perhaps some are. But I suspect it would be more accurate to call the time off “burnout-recuperation days.” Whether teachers will claw back enough time to regain their equilibrium remains to be seen.

A related issue: the media accounts I’ve read do not indicate whether teacher time off, which translates directly into less classroom teaching time, will be made up at the end of the year; if not, students who need to spend more time in school to catch up, could in fact end up spending less time in class this year.

The afflictions of long-haul school COVID appear to be as acute as the original illness. The slide toward utter collapse continues unabated at many Virginia public schools. Governor-elect Glenn Youngkin may discover that there are more pressing problems than ridding schools of Critical Race Theory and pornographic books.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.