Virginia’s overall unemployment rate has been declining steadily for years, reaching 3.2% in June 2018. But youth unemployment remains disconcertingly high. Indeed roughly 10% of the state’s 16- to 24-year-olds are “disconnected” from the labor force, neither working nor pursuing an education, reports Shonel Sen, a researcher with the Demographics Research Group at the University of Virginia.

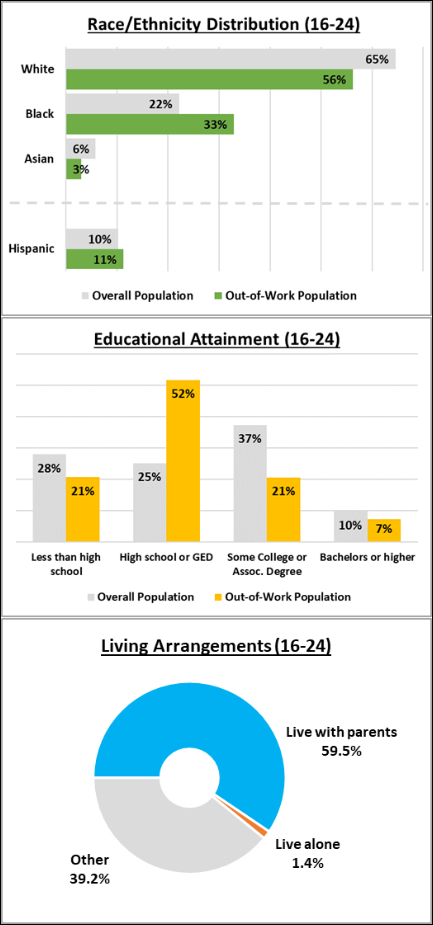

Living up to stereotype, almost 60% of disconnected youth still live with parents. A majority of the economic dropouts are white, although a significant minority are black, Sen writes in the StatChat blog. While one out of five is a high-school dropout, half have high school degrees or GEDs, one out of five has some college, and 7% have B.A. degrees or higher.

The phenomenon of disconnected youth is troubling, writes Sen. The failure to enter the workforce may impair the ability of young people to find and keep steady jobs later in life.

These teens and young adults are neither attending high school nor working, and this level of disconnectedness represents an entirely different set of circumstances for younger people than those faced by older adults who may currently be out-of-work. For youth who are disconnected from both school-networks and workplaces at this crucial point of emerging adulthood, the consequences of this disconnection can have a lasting impact on lifetime work habit development and social, physical, and financial well-being.

Engaging these youth may require different public policy responses that programs designed to bring adults with a history of work back into the labor force, Sen suggests.

Investing in pathways to affordable and accessible post-secondary education will yield a high return. Targeted policies that attempt to reduce high school dropout rates, provide apprenticeships and training opportunities, and open up career pathways for this vulnerable youth population will greatly benefit not just these individuals, but also society at large.

Perhaps. Government programs might be the answer… But I’m not confident that government can address what may be a cultural phenomenon or symptom of a mental-health crisis.

The data, drawn from the 2012-2016 American Community Survey five-year estimates, provides an incomplete snapshot. The demographic and educational variables it highlights may not be the key drivers behind the stay-at-home phenomenon.

How many of these disconnected youth are paralyzed by mental health issues such as depression and anxiety? How many engage in substance abuse? How many don’t appear to be working but actually are working — in the black market economy? How many are anti-social recluses who dither away their time playing computer games?

Here’s one clue: Asians constitute 6% of Virginia’s population but only 3% of disengaged students. Why is that? One possible explanation is that Asians tend to reach higher levels of education, and education level is a critical variable in youth disengagement. Another explanation is that in tight-knit Asian sub-cultures, youth suffer less from depression, anxiety and substance abuse. Alternatively, perhaps Asian families have lower tolerance for slacker behavior and don’t mind confronting non-performing children and getting them off their duffs.

Opening up “career pathways” might help some disengaged youth. But I doubt that a lack of apprenticeships and training is the problem for most. Frankly, we don’t fully understand what’s going on.

Sen has highlighted a fascinating problem, though. As Virginia’s economy suffers from chronic labor shortages, it is in society’s interest — and in the interest of the young people themselves — to find ways to help the disengaged youth become productive citizens.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.