How widespread is social promotion in Virginia schools, and how deleterious are the consequences? Those are critical questions to ask as the Mo’ Money crowd beats the drums for more state support for K-12 education, more programs to address social “inequity,” and a slew of other initiatives all premised upon the idea that the way to improve educational outcomes is to do more of what isn’t working.

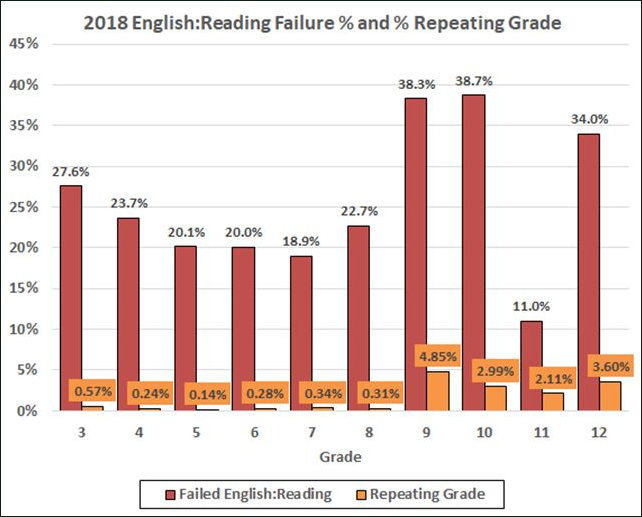

Over at Cranky’s Blog, John Butcher provides valuable perspective on the social-promotion issue. He has juxtaposed two data sets: the percentage of public-school students who fail their SOLs, thus indicating a failure to master the subject matter, and the number who are held back to repeat a grade.

As can be seen in the graph above, there is a vast and yawning gap in English reading. Virginia 3rd graders fail their English SOLs at the rate of 27.6% but only 0.57% are held back — a gap of 26%. The gap becomes a chasm by high school. Social promotion is far more widespread than I ever imagined.

The drawback of social promotion is obvious: If a student fails to master 5th grade math, for instance, advancing him to the next grade just increases the odds that he will fail to master 6th grade math. To the contrary, he likely will fall further behind, becoming more frustrated and alienated with each passing grade. I would hypothesize that socially promoted students are far more likely to disrupt classes and far more likely to drop out of school. Furthermore, social promotion may not even do the one thing it is designed to do: save the student from the social stigma of failure. An inability to master academic material year after year is not likely to improve one’s self-esteem.

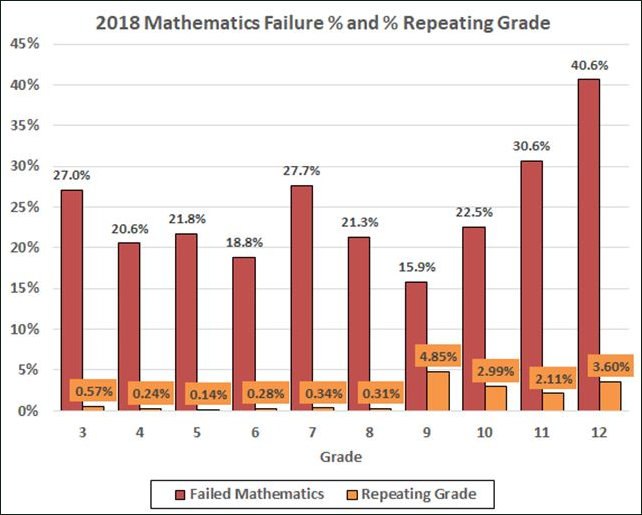

Cranky demonstrates that the gap between SOL pass rates and repeated grades applies also to writing and, as seen below, math.

I’m not suggesting that every kid who fails to pass an SOL exam should be held back. Maybe the kid was just having a bad day when he took the test. Maybe the exam results were at odds with his math grades. Maybe he fell short of passing by just a hair. Maybe he’s been showing improvement, even if he fell short in the test. Maybe he passed all his other subjects, and holding him back a grade for failing just one subject seems like overkill. I get it — a lot more than test results should go into the decision whether or not to hold back a student a full year.

But let’s postulate for purposes of argument that half the kids who fail to pass their SOLs are not held back but should be. That would imply anywhere between 10% and 15% of Virginia students are being socially promoted. Absolutely no one in the Virginia educational establishment, to my knowledge is grappling with this issue. Social promotion is untouchable. Instead, progressives in the educational establishment blame racism, discrimination and insufficient funding for the persistent racial differences in SOL test scores.

The progressives’ answer is twofold. First, mo’ money. The answer is always mo’ money for more teachers, pay increases for teachers, more support staff, more administrators, and newer buildings. The failure to deliver mo’ money is construed as a perpetuation of racism and discrimination. The other answer is to paper over the malignant effects of social promotion with “social equity” policies, the most recent iteration of which is to implement a “restorative justice” approach to discipline. So, when socially promoted kids “act out” in class, traditional sanctions such as in-school and out-of-school suspensions are applied only as a last resort. As a consequence, more classrooms are disrupted, teachers are distracted more often, and other students spend less time learning.

When the Virginia Board of Education is telling us we need to boost K-12 spending by $950 million a year to carry out its “progressive” vision of education, it’s time to question underlying assumptions and sacrosanct practices. It’s time to talk about social promotion.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.