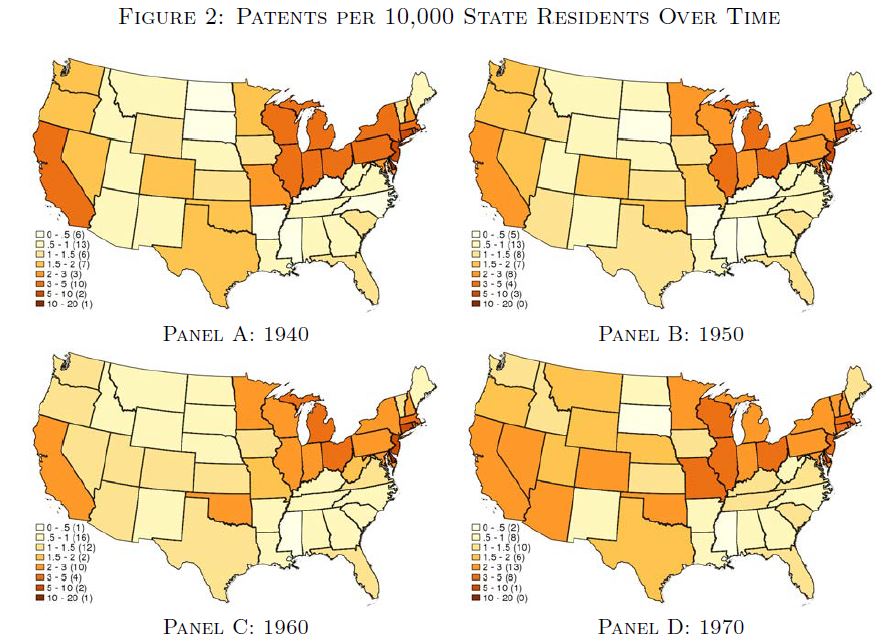

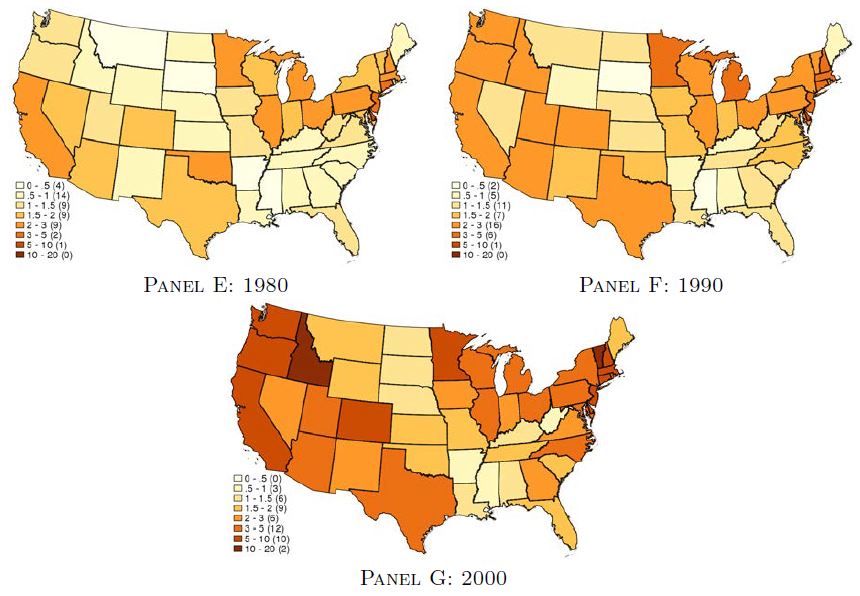

In 1940, technological innovation in the United States was concentrated overwhelmingly in the Great Lakes states, the Northeast, and California. The powerful economic force known as agglomeration — in which geographic proximity boosts the productivity of inventors and researchers — acted to perpetuate those states’ lead. Yet over the following six decades, the propensity for innovation, as measured by patents per 10,000 state residents, diffused to Texas, the South Atlantic states (including Virginia), and the Rocky Mountain states. What drove that change?

One likely factor was tax rates — primarily for corporate income taxes, but for personal income taxes as well. And that should be a wake-up call to Virginia. The Old Dominion’s 6% top marginal tax rate for corporations gives the state a crummy 31st rank in the Tax Foundation’s business tax climate index, and its 5.75% top tax bracket contributes to the state’s 9th highest rank for state-and-local income taxes paid per year.

A new study by Ufuk Akcigit, a University of Chicago economics professor, and three colleagues has found that corporate and personal income tax rates have a profound effect over long periods of time on technological innovation. States their paper, “Taxation and Innovation in the 20th Century“:

Taxes affect the amount of innovation, the quality of innovation, and the location of inventive activity.

The effect of taxes on innovation is a consuming question in modern-day economics. Heavily dependent upon anecdotal evidence and incomplete data, the debate has been impossible to resolve decisively. However, Akcigit and his co-authors have set a new evidentiary standard by compiling three new datasets. First they constructed a database of inventors based on historical patent data since 1920, which allows them to track innovations over time, industry, and location. Secondly, they built a database of corporations’ R&D labs and research employment. Thirdly, they created a dataset of state-level corporate and personal income tax rates.

The authors find that personal and corporate income tax rates have “significant effects” at the state level on patents, citations (a measure of the significance of a given patent), the prevalence of inventors in a state, and the share of patents produced by firms compared to those produced by lone inventors.

Corporate inventors are the most “elastic” — economics speak for “sensitive” — to tax rates. Corporations tend to be unsentimental about where they invest. They have less loyalty to a given geographic area. They look to maximize their return on investment wherever they can find it. By contrast, individuals may have strong personal and sentimental attachments to a location. However, when inventors do choose to move, Akcigit has found, they are “significantly less likely” to move to states with higher taxes.

Though a significant factor in shaping the geographic distribution of innovation, taxes are not all-powerful. The authors readily acknowledge the influence of agglomeration effects. Within a given scientific or technological field, inventors like to stay close to the action — in other words, to locate near others in the same field. Often, agglomeration effects are stronger than tax rates.

Bacon’s bottom line: Let me offer a couple of refinements, and then a warning to Virginia.

The authors examine published corporate income tax rates. They do not take into account the impact of corporate tax giveaways — an essential strategy for some states (such as New York) to retain corporate activity and for other states (such as anyone trying to attract Amazon’s HQ2) to bribe corporate investors. Also, they don’t examine how the tax money is spent. In theory, highly skilled and educated inventors prefer to live and work in locations with superior amenities made possible with higher taxes. Finally, they neglect to examine university-generated R&D. It goes without saying that university R&D is tied to the geographic location of the institution (although research teams can be induced to move).

I would argue that powerful forces work to perpetuate the geographic status quo:

- Agglomeration effects, in which inventors in industry clusters feed off one another. Silicon Valley is a classic example of how agglomeration effects outweigh the negative impact of high taxes and even higher real estate prices.

- Government and cultural amenities, in which wealthy regions of the country spend more money on schools, higher-ed, and other amenities valued by the educated class, and where philanthropists have endowed local universities, medical centers, and arts & cultural institutions over the ages.

- Tax-favored institutions, in which leading universities, disproportionately located in the Northeast, the Midwest and California, have accumulated massive tax-exempt endowments that allow them to underwrite the recruitment of world-class research faculty. Insofar as universities serve as anchors for innovation ecosystems, this tax advantage is crucial.

It is remarkable, given the extraordinary advantages of the incumbent innovation leaders, that research and innovation has migrated to other states at all. What allows these other states to compete? Lower corporate and individual taxes is one of the few public policy tools a poorer state can muster.

Once upon a time, Virginia was known as a low-tax, fast-growth state. That is no longer true. At best, we can claim to be a moderate-tax, moderate-growth state. We have neither the advantage of accumulated wealth in the form of world-class research universities, medical centers, foundations, museums, and cultural institutions nor the advantage of lower taxes that attract corporate investment. (Yeah, yeah, the University of Virginia is great, and so is the Virginia Museum, but overall Virginia is strictly second-tier.) Measured by economic performance, Virginia is in the muddled middle. Economic growth is plodding. For the first time in decades, more native-born Americans have been leaving the state than entering it.

Is our tax policy to blame? Do our tax structures and budgetary priorities increasingly resemble those of the Midwestern and Northeastern states — without the inheritance of vast industrial-era wealth and philanthropy to underpin our economy? I suspect strongly that that’s the case.

To answer the question, it would help to have innovation data more recent than 2000. Economically speaking, Virginia was on a roll then. Today, the state is suffering economic malaise. I would not be surprised to find that our relative innovation standing has declined. Our governor and legislature propose lots of small-small remedies to jump-start the economy, but it’s hard to see how they will amount to much. Virginia’s relative decline warrants far more serious thought than it has received so far.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.