by Carol J. Bova

The looming COVID-19 hospital crisis in Southwest Virginia was set in motion long before the pandemic.

To begin with, the region’s health indicators and outcomes generally are much worse than the state average. Two indicators particularly impact the COVID-19 epidemic: Every county in the Southwest Virginia Health Authority service area has a higher percentage of obese adults than the state as a whole. Similarly, the diabetes rate in the counties of Lee, Scott, and Wise, and the City of Norton is 19.1%.

Against this comorbidity backdrop, a nursing shortage at the region’s largest health provider, Ballad Health, is making it impossible to staff enough hospital beds to serve Southwest Virginia’s COVID-19 patients.

On December 2, 2020, VaDogwood.com reported from information supplied by Ballad Health: “Due largely to this nursing shortage, Ballad Health is nearly at capacity. The system is at 93% patient occupancy, including 92% of all ICU beds. Furthermore, more than 200 staff members are currently isolated or in quarantine due to confirmed or potential infection.”

Ballad Health CEO Alan Levine described the dilemma: “Ballad Health has the supplies it needs to treat coronavirus patients. It has the bed space and ventilators. But capacity is determined by the staff availability. Given the nursing shortage the system is facing, the key at this point is to keep as many people as possible out of the hospital.”

Ballad has already halted elective surgeries that require an overnight stay in order to shift staff, but it still needs to hire 350 more nurses.

To put this situation into context requires a look at the merger creating

Ballad Health.

In June, 2019, the Tennessean, part of the USA Today Network, published ”Medical monopoly: An unusual hospital merger in rural Appalachia leaves residents with few options.” The article discussed what the publication called “an unusual and controversial merger between two rival hospital systems headquartered in northeast Tennessee.”

On October 30th, 2017, Virginia’s then-State Health Commissioner, Marissa J. Levine, approved an application in a Letter Authorizing a Cooperative Agreement between Mountain States Health Alliance and Wellmont Health System to merge under the name of Ballad Health. (According to the 151-page document, the Southwest Virginia Health Authority had recommended approval in November, 2016.)

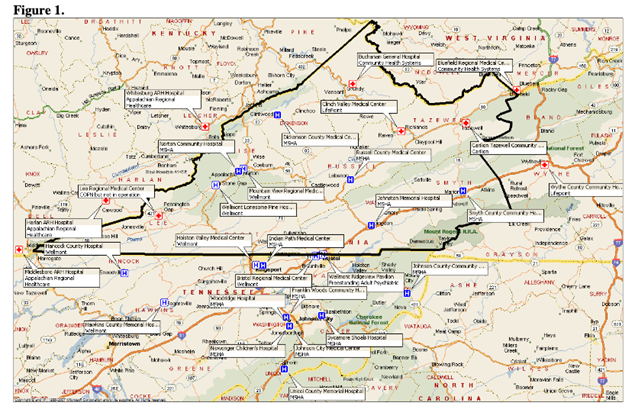

The merger creating Ballad Health affected 29 counties in northeast Tennessee and nearby parts of Virginia, North Carolina and Kentucky, a region the size of New Jersey.

In an August 2019 report of its first year, Ballad pointed to a national shortage of nurses as a concern, noting that it would make a $10 million annual investment to boost direct-patient care nursing wages, affecting nearly one-third of Ballad Health’s workforce.

Ballad said it used its entire operating income of $9.9 million in fiscal 2018 to do this. Only later in the report did it mention that for the year ending June 30, 2019, operating income had risen to $36.5 million. The health system attributed the improved finances to expense and supply cost management and reduced reliance on temporary contract labor. In a different context, it also noted that it had reduced “the use of temporary traveler nurses by 50% over the last year.” It did not say how many jobs were eliminated by the 50% reduction.

The Southwest Virginia Health Authority (SWVA) created a Task Force in 2019 to oversee Ballad for Virginia and hired three staff members to help it navigate the application for a cooperative agreement. One of the three, Dennis Barry, a retired healthcare attorney, serves as the merger monitor.

The terms of the merger set goals of spending $75 million over ten years for population health improvement and investments of $70 million over ten years to address differences in salary and benefit structures among employees in the new health system.

Unlike in Tennessee, the Virginia Department of Health says “it closely monitors Ballad, but reports are not available to the public.” (Roanoke.com went on to say in a January 6, 2020 article:

Two years since the creation of Ballad, the state has yet to release quality, access and financial reports with the public. And people living in far Southwest Virginia have yet to be given a public forum to tell regulators whether Ballad is living up to a list of conditions to ensure access to health care, to improve its quality and to do so without hiking prices.

In his first report as Merger Monitor to the SWVA Board on January 3, 2020, Barry said that, while Ballad is taking steps to recruit and retain more nurses, the nursing and allied health shortage will not be alleviated in the short-term and is likely to continue to affect Ballad and its patients for at least the near-to mid-term future. One item on the Authority’s Merger Monitor’s agenda is to research more fully what Ballad is doing to address the problems caused by the nursing shortage.

On December 2, 2020, VaDogwood.com quoted Ballad Chief Physician Executive Clay Runnels as saying that Ballad Health was hoping to increase capacity to 460 beds specifically for COVID patients. However, the publication added, “given the rate at which the virus is spreading in the region, Ballad is heading for a peak of more than 500 people hospitalized by the end of December. Currently, there are less than 15 ICU beds available across the entire system.”

The merger application indicates a reduction from 526 licensed hospital beds in Virginia to 341. Ballad Health hospital websites do not give total number of beds. In the chart below, 2013 and 2015 are compiled from the Ballad Health Merger Application /VHI; 2020 numbers come from Virginia Health Information (VHI).

According to minutes posted online, when the Southwest Virginia Health Authority Task Force met on November 19, 2020, Barry advised that Ballad had submitted the required annual report to compliance monitors at the end of October, 2019. The report had two portions — one, 270 pages long, contained nonconfidential information; the other, more than 300 pages long, contained information that Ballad had identified as being confidential, proprietary, or containing commercial/business information that it couldn’t disclose. Copies were not included in the meeting packet.

The November, 2020 Task Force meeting, the agenda called for Barry to address several issues, among them:

• Terms of the Cooperative Agreement and Tennessee requirements suspended during COVID-emergency.

• The effects of COVID-19 on Ballad, presented by Ballad with slides

submitted in advance.

• Ballad’s financial results for FY 2020, and budget for FY 2021

(confidential if Ballad wants to treat it that way, presented by Ballad with slides submitted in advance.

• Determination of spending shortfall.

• Problems with the Cooperative Agreement and the Tennessee Terms of Certification are becoming apparent.

The issue of Ballad’s nursing shortage was conspicuously absent from the list, as were details of which merger requirements were suspended.

The Southwest Virginia Health Authority (SWVA) Board will meet by Zoom on December 9th, but there is no information packet online yet to see further details on the November Task Force meeting.

Update and Correction: On June 24, 2020, the Virginia Department of Health did post online the “Virginia State Health Commissioner’s Annual Decision Regarding the Ballad Health Cooperative Agreement for the period of June 1, 2018- June 30, 2019. This document was not included in the Southwest Virginia Health Authority Task Force November 19, 2020 meeting packet or SVHA website.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.