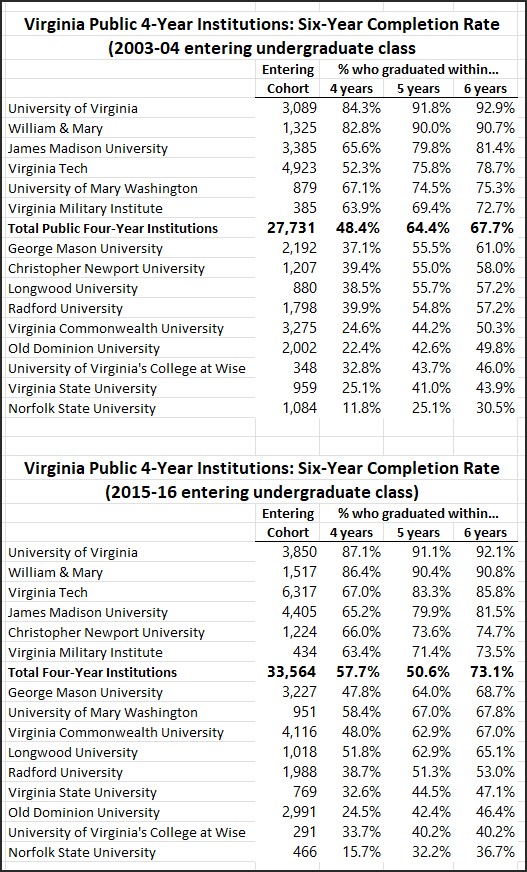

The dirty secret of the higher-ed industry is the high rate at which students drop out of college. The six-year graduation rate for full-time, in-state students entering Virginia’s public four-year institutions in 1995 was 60%, implying a drop-out rate of 40%, according to State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) data.

After Virginia institutions made strenuous efforts to improve performance, the rate increased to 73% for the 2015 entering class — a big improvement. But there is still a long way to go — and it’s not yet clear from the published data what impact the COVID pandemic had on completions.

A high drop-out rate is a major social issue. Thousands of Virginia students spend tens of thousands of dollars, often borrowed, on tuition, fees, and room and board without ever acquiring a credential to improve their job prospects. Recognizing the problem, SCHEV has issued a report, “What Matters Most,” which explores how Virginia higher-ed can get better results.

The report contains some useful perspectives. But, as one might expect from a document compiled with input from university administrators with vested interests and sacred cows to protect — deans of students, vice presidents of student affairs, vice presidents of admissions, student support services administrators, and unspecified “subject matter experts” — it has blind spots as well.

The report views the issue of college completions through four lenses: (1) college/life preparedness; (2) mental health and well being; (3) basic needs; and (4) sense of belonging.

College/life preparedness. The authors suggest that students must possess academic proficiency, sound study habits, and determination to graduate — attributes which, ideally, they had developed before entering college. The pandemic and shift to remote learning in K-12 schools resulted in the loss of 15 weeks equivalent of math instruction and 11 weeks of reading.

Though harder to measure, remote learning adversely affected students’ social development and emotional maturity. The report discusses the value of “resilience,” otherwise known as “grit,” or the ability to move past challenge and failure in positive ways. Without quite saying so, the report suggests that kids entering college today are less resilient thanks to COVID.

Mental health. A student’s resilience is closely tied to his or her mental health and well-being. Nationally, 40% of college students have reported having a mental disorder, most commonly anxiety or depression. Students dogged by anxiety and depression find it far more difficult to persist in the face of adversity.

Basic needs. Students who are stressed by the challenge of paying for housing, food and even child care have a harder time completing their courses of study. Material need can be compounded by shame and can result in students’ inability to participate in college activities, which in turn can contribute to mental health issues. Nationally, 48% of college students face housing insecurity, and 29% of four-year college students deal with food insecurity. Nearly 61,000 students at Virginia higher-ed institutions are eligible for SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program) but are not receiving benefits.

Belonging. “Belonging” is a buzz word in higher-ed. The idea is that students who feel part of the college community are more likely to succeed. Belonging means feeling welcome, fitting in, finding friends, engaging in campus life, and making personal connections to professors and coursework. A national survey of 1,000 students found, however, that more than a third felt alienated from their courses, their peers and their colleges. First-generation students (the first in their family to attend college) and financially insecure students are particularly likely to have trouble fitting in, the study observes.

The SCHEV report acknowledges there are no quick fixes to these problems, and that “one size fits all” solutions are not advisable. With those caveats, the report proposes more funding to address basic student needs, provide mental-health resources, and focus resources on “marginalized student groups.” Where the money would come from is not clear.

Bacon’s bottom line: The analysis seems reasonable as far as it goes. But it is incomplete.

First, it underplays the issue of academic preparedness. There is a widespread sense in our society that everyone who wants to go to college ought to be able to. Many young people are not academically equipped for college-level learning. Thousands require remedial work in math, reading and writing. But as enrollments decline due to a shrinking college-age population, institutional demand for students is voracious, and the temptation to relax admissions standards is very real. For ideological reasons, the temptation is more acute for disadvantaged minority students who, in many cases, have graduated from low-performing schools with entirely unrealistic expectations of their abilities. Sadly, when confronted with the demands of college-level work, many of these students feel overwhelmed and drop out.

Second, the issue of “belonging” is especially a problem in the age of heightened social-justice consciousness. The prevalent view among college administrators is that putting a student’s race, sex and gender at the center of his or her identity is the way to foster belonging. Give Black students their own dormitories, their own social facilities, and their own ceremonies; in effect, encourage them to self-segregate, all the while creating a sense of racial grievance over micro-aggressions and other perceived manifestations of racism. How heightened race consciousness is supposed to make Black students feel at one with the university community is unclear. Whether the strategy works is never examined.

In other words, the university officials whose input informed the SCHEV report are captive to their professions’ social-justice consciousness. Unwilling to question a core assumption of their belief system, they ignore it in their analysis of college completions. Thus, potentially important drivers of student graduation rates are never explored.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.