by James A. Bacon

Broadly speaking, there are two approaches to dealing with increasingly stringent clean water regulations. One is to make incremental upgrades with the idea of deferring expensive capital outlays as long as possible, which is what most local governments do. The other is to go big and go bold — the option pursued by the Hampton Roads Sanitation District (HRSD) in its $1.2 billion Sustainable Water Initiative For Tomorrow (SWIFT) project.

As a regional sanitation district serving a population of 1.7 million, the HRSD has the size and resources to undertake projects of a magnitude that smaller municipal systems could only dream about. Under regulatory pressure to reduce algae bloom-causing nitrogen and phosphorus from wastewater released into the Chesapeake Bay, HRSD is implementing an ambitious scheme to treat the water and then pump it back into the Potomac aquifer. The hoped-for result is to slow the rate of land subsidence that contributes to increased flooding in the region.

HRSD’s ambitions are on display at a $25 million research center in Suffolk near the Monitor-Merrimac bridge tunnel. There, researchers are tweaking the process for cleaning about one million gallons daily — not only removing phosphorous, bacteria and viruses but breaking down organic chemicals found in medications tossed into sinks and toilets — to drinking water quality. By 2030, HRSD will apply the technology in five full-scale facilities capable of treating around 100 million gallons daily.

“Groundwater levels have dropped 200 feet in the last one hundred years,” says Jamie Mitchell, HRSD chief of technical services. “The U.S.G.S. (U.S. Geological Survey) estimates that half the relative sea level rise in Hampton Roads is due to subsidence. About half of that is due to withdrawal” from the Potomac aquifer. With the loss of offsetting pressure from the aquifer water, the land above sinks a few millimeters each year, adding up to a few inches over the decades.

With the potential to slow relative sea level rise by 25% or so, the SWIFT project will give the region more time to adapt to the inevitable increase in inundation and flooding. As a bonus, the project may address the water-shortage affecting major users like paper mills.

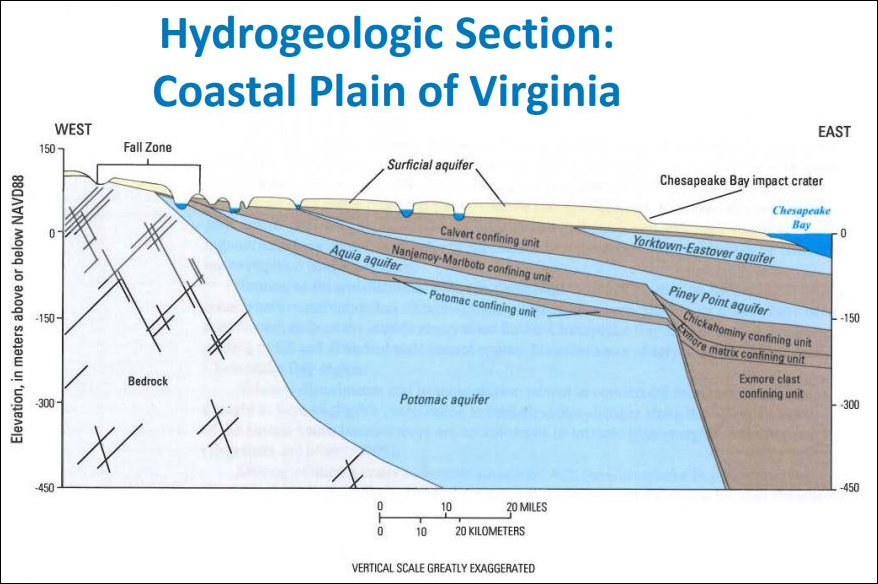

The geology underneath Hampton Roads is complex. Two thousand feet beneath the surface is bedrock. Above the bedrock are layers of impermeable clay and looser materials through which water can migrate. Three thin aquifers lie at relatively shallow depths under the surface, which residential property owners can tap with private wells, but the largest and deepest source of groundwater is the Potomac aquifer, a complex system which is fed by water infiltrating the ground around the fall line of the James River.

Municipal governments and manufacturing plants have tapped the Potomac aquifer for decades. But around a decade ago, the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) became concerned about the aquifer’s rapid rate of depletion. In the past natural pressure pushed the water to the surface. Now, pumping is required to extract it. Meanwhile, the loss of water pressure allows salt water intrusion from the Atlantic Ocean, which would ruin the aquifer for human consumption and industrial use.

In 2013 DEQ began scaling back permits for the rights to withdraw the groundwater, focusing on the 14 users biggest users. These users, which include James City County and the paper mills in Franklin and West Point, were allowed to withdraw no more than 145.6 million gallons per day. The price tag for developing alternative water supplies, such as piping water in from Lake Gaston on the Virginia-North Carolina border, building reverse-osmosis treatment facilities, and taking water from the Chickahominy River, would run into the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Meanwhile, another huge set of costs is looming. Local governments are under the gun for the nitrogen and phosphorus in stormwater runoff into the Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries. By going over and above conventional wastewater treatment process and reducing nitrogen and phosphorus content to 10% of untreated levels, SWIFT will generate nutrient credits that will help the region meet tighter TDMLs (Total Maximum Daily Loads) and spare localities the need to scrounge up roughly $1 billion for stormwater retrofits.

HRSD will cover the $1.2 billion SWIFT cost by deferring work required by the Environmental Protection Agency to address sewer overflow. The EPA encourages local governments to prioritize investments to accomplish projects with the most significant environmental benefits first, and SWIFT looks like the best of the options. The benefit that comes from slowing the rate of subsidence and relative sea level rise is a big extra. (SWIFT will not affect subsidence that occurs from a gradual shifting of tectonic plates.)

“We can’t quantify the value of halting or slowing subsidence,” says Mitchell. “But it should buy time [for Hampton Roads] to adapt and innovate.”

The experimental SWIFT facility, designed and built by Charlotte, N.C.-based Crowder Constructors, Inc., is highly automated and requires the periodic presence of only three HRSD employees daily. As a research facility, it also hosts six to eight researchers, typically employed by Virginia universities, investigating ways to cut process costs and improve public health.

Currently, HRSD treats wastewater to state and federal standards and releases it into Virginia waterways. SWIFT takes the wastewater through several additional steps. One stage in the treatment process injects ozone into the water — ozone is a highly reactive molecule consisting of three oxygen atoms — that inactivates pathogens such as protozoa and viruses by breaking them down into organic materials, which microbes embedded in a carbon medium can absorb in a biofiltration process. To kill off any surviving pathogens, SWIFT zaps the water with ultraviolet light.

At this point the wastewater is clean enough for human consumption — and SWIFT tour guides invite visitors to drink it from a fountain. But the water must be subject to further treatment before being put back into the aquifer. The goal, says Mitchell, is to match the “native groundwater chemistry” as closely as possible, which means matching concentrations of salt, manganese, fluoride and other chemicals found naturally in the groundwater.

Mitchell quickly dispenses with the idea that “fresh” aquifer water resembles the water that comes out of a sparkling mountain spring. All groundwater absorbs chemicals from the material through which it flows. The Potomac aquifer is notable for its high level of fluoride — a level that was so high that the City of Suffolk had to shut down several private wells. It is important to match the background aquifer water, she says, because a different chemical composition could react with clays and other materials in ways that would alter the aquifer’s natural functioning.

In the final stage, SWIFT delivers the treated water back into the aquifer through a well dug to a depth of about 1,500, and it has set up sensors in the main well and nearby test wells to study what happens to it. After several months in operation, the 140 million gallons injected so far have migrated only a few dozen yards. It takes a couple hundred years for water in the Potomac aquifer to travel a mile, which is an indication of the aeons of time it would take to replenish the entire aquifer naturally.

SWIFT is not a magic bullet that will solve all of Hampton Roads’ water shortages or subsidence issues. The region will have to explore many avenues, including water conservation, exploitation of surface water sources, and perhaps even desalination. But by putting 100 million gallons per day back into the Potomac aquifer, the project will buy the region time. And time may be the scarcest resource of all right now.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.