Source: Virginia Supreme Court

By Dick Hall-Sizemore

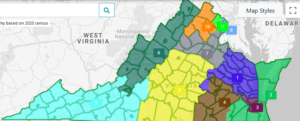

The redistricting for General Assembly seats and those in the U.S. House of Representatives is complete. The Virginia Supreme Court issued its final order and approved maps on December 28, 2021.

There are some significant changes from the earlier proposed maps. For a discussion of the first maps released by the Supreme Court’s special masters, see my earlier post here.

The report of the special masters is a good example of civic education. They explain, in plain language, why “redistricting is a complex task, one that requires the balancing of multiple competing factors.” It is not a simple matter of dividing the state into X number of evenly populated pieces. One example of this balancing act can be seen in their treatment of the Shenandoah Valley. They made a policy decision at the beginning to treat the Valley as “an important community of interest worth preserving.” Thus, they avoided drawing districts that crossed the mountains. However, they point out “that comes at the expense of drawing compact districts, particularly at the congressional level.” Succinctly put, “Tradeoffs are simply inevitable.”

When the Supreme Court released the first drafts of the maps in early December, it invited public comments and provided several formats: comments inserted directly onto interactive maps; written comments, including submission of alternative maps; and two virtual public hearings. It is evident from their report that the special masters took these comments seriously and, in many cases, made changes based on those comments. Much of the report is devoted to explaining these changes or explaining why they did not, or could not, accommodate some of the changes recommended.

General areas of concern

In the report, they address the major areas of criticism or concern raised in the comments. Summaries of some of those areas follow:

Incumbency. “The most common criticism was that we paid insufficient attention to incumbency, weakened several congressional incumbents, and paired together multiple senators and delegates.” In response, they reiterate that, originally, they did not actively determine where incumbents lived and, after consulting with the Court, continued to use that approach.

Having expressed this attitude, they brush off the criticism by pointing out that protecting incumbents is not one of the criteria laid out in the Virginia Code. Furthermore, protecting incumbents “would seem to be at odds with the overall redistricting scheme enacted by Virginia voters” in approving the constitutional amendment establishing the Virginia Redistricting Commission. Finally, they conclude their “treatment of incumbents [is] an example of the redistricting process working as intended.”

The special masters point out the obvious reason that so many incumbents are affected: many live relatively close to one another, and the 2011 maps were drawn to keep incumbents in separate districts. Therefore, many of the current districts have odd shapes and are not compact. For their work, they did not use incumbents’ residences as a criterion and the new maps split fewer counties and cities fewer times. “Any redistricting map featuring this degree of geographic consolidation will almost certainly pair incumbents together; if those incumbents live in a narrowly-defined geographic area, the chances of being paired together are increased.” They conclude by saying, “Having established compact districts that respect communities of interest … our hope is that future redistricting utilizing the same criteria will be less severe.”

Communities of interest. Their explanations of the changes in the maps make it obvious that the special masters paid attention to comments regarding the splitting of communities of interest. Many of the changes were made to follow the lines of “census designated places,” for example. Nevertheless, in some areas, they found it difficult to do so. One of those areas was the Roanoke Valley/New River Valley area. “We received so many contradictory claims regarding what areas should be included in which districts and where exactly the COIs [communities of interest] lay.” Therefore, they left the maps largely as they had been originally drawn.

Partisan balance. This was one of the trickier areas. As the special masters explain, they originally agreed to draw the maps without referring to partisanship, then “unblinding” themselves to ensure that the “median district in the state roughly reflected the statewide performance of the parties.” This was their test to ensure that they met the statutory requirement that the redistricting did not “unduly” favor or disfavor any political party. In the end, they “accomplished this task of creating an unbiased map naturally, using neutral principles, and did not need to adjust the maps we had drawn in a partisan blind fashion.”

However, after the maps were released, the partisan information became available and the special masters could not “re-blind” themselves. Moreover, they became “wary of allowing ourselves to be used as cat’s paws by those who might have seen the comment period as an opportunity to guide us toward a partisan gerrymander under the guise of preserving communities of interest or drawing compact districts.” As a precaution, they made changes to the maps only if doing so could be done in a way that was neutral to partisanship since the maps were already well balanced. In summary, they were careful not to “put our thumbs on the scale in a way that would … tilt the map toward either political party.”

14th Amendment and ability-to-elect districts. The special masters were under pressure from various groups to modify their original maps to give more emphasis to racial minorities. They rejected all these attempts and stuck with their original approach of beginning “with the good government criterion of preserving whole counties and cities to the extent possible.” By utilizing this approach, they felt that districts with substantial minority populations would result from the “racial geography of Virginia.” After they had originally drawn districts that satisfied good government criteria, they discovered that the maps resulted in two minority “ability-to-elect” districts in the U.S. House of Representatives as is the case currently and more “ability-to-elect” districts in the General Assembly. They saw no reason to modify the maps on these grounds.

Specific changes

Following are summaries of the changes made in the three maps.

Congressional districts

The most dramatic changes occurred in this map. There were also many minor changes, especially ones related to population equalization. The result of these population-related tweaks is that the deviation from the ideal population is zero in all but one of the districts and the deviation in that district is one person.

Districts 9 and 11. (Northern Virginia). Minor changes, based on written comments submitted to the Supreme Court.

Districts 6 and 9 (Appalachia and Shenandoah Valley). Minimal changes, primarily moving Craig County into the 9th District and moving some Roanoke County precincts from the 9th to the 6th district.

Districts 2 and 3 (Hampton Roads and Virginia Beach). There were a lot of pleas to use the 3rd District as established in the earlier federal redistricting or to pair Norfolk with Virginia Beach, rather than with Hampton and Newport News. The special masters report that it was difficult for them to separate legitimate concerns from a desire to protect an incumbent (Rep. Elaine Luria (D)) or to alter the partisan balance. Therefore, they made no changes.

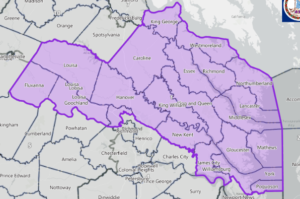

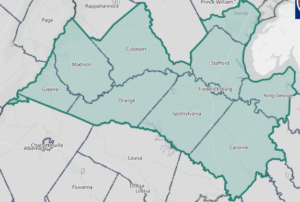

Districts 1,4, 5, 7, and 10 (North Tidewater, Richmond area, and outer Northern Virginia). They made significant changes in these districts. The main impetus for the changes came from the configuration of the 1st District in the original maps. In that proposal, the district stretched from the Chesapeake Bay to the Albemarle County line, encompassing the Northern Neck, Middle Peninsula, western Henrico, and the rural counties of Louisa, Goochland, and Fluvanna.

Many residents of those western rural counties expressed unhappiness with being in a Tidewater district. In addition, there was a lot of resistance to the Richmond area being split among three different districts (1, 4, and 5). Further west, there was unhappiness with Albemarle County being split between the 5th District (largely Southside) and the 10th District, anchored in Northern Virginia. The special masters acknowledged that “the inclusion of Fluvanna, Louisa, and Goochland counties in the Tidewater area is indeed not a natural fit” nor was including Albemarle County with Northern Virginia a natural fit.

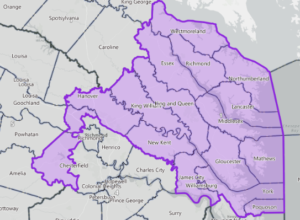

To address these concerns, the special masters moved all of Albemarle, along with Louisa, Fluvanna, and Goochland to the 5th District, and that part of Chesterfield that was in the 5th District to the 1st District. The result is a strange-looking district that curls around the western boundaries of the Richmond area. (See illustrations below.) It could be termed “good gerrymandering,” because the district owes its shape to the sparser population of the Northern Neck and Middle Peninsula, as well as to desires to better represent communities of interest and to preserve the Richmond, Henrico, and Chesterfield area in two Congressional districts, rather than splitting the area three ways.

Source: Virginia Supreme Court

Source: Virginia Supreme Court

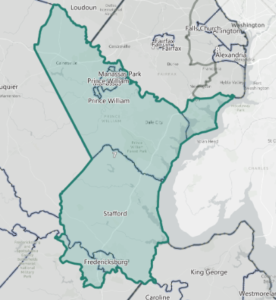

Those changes in the 1st and 5th districts necessitated changes in the two districts affecting Northern Virginia (7 and 10). The district most affected was the “new” 7th. Originally, the special masters had “relocated” the 7th to the Northern Virginia suburbs because they felt that the increased population of the greater Northern Virginia area called for a fourth district, rather than the fracturing that had defined the current map. To accommodate the desire to keep the 7th District anchored in Prince William County, as well as the changes made in the ,1st, 5th, and 10th districts, the 7th District went from being oriented basically north-south, running from Prince William to Fredericksburg to an east-west orientation, still anchored in Prince William. (See Illustrations below.)

Source: Virginia Supreme Court

Source: Virginia Supreme Court

As was the case with the original Congressional maps, three sets of incumbents got paired in a district. However, only one is adversely affected. Morgan Griffith (R) is paired with Ben Cline (R) in the 6th District, but Griffith has represented the 9th since he was elected to Congress, without having actually resided in the 9th.

Abigail Spanberger (D) and Rob Wittman (R) will still be paired in the newly drawn 1st District. Spanberger currently represents the “old” 7th District, which has been moved northward. Her current district is a toss-up, but the 1st District leans Republican, although less so than it did in the original map. Interestingly, Spanberger has announced that she will run for re-election in the newly-drawn 7th District, in which she currently does not reside. The new 7th District is considered to lean Democratic and contains three counties which she represented in the old 7th District.

The third incumbent pairing is Bobby Scott (D) and Elaine Luria (D) in the newly drawn 3rd District. Luria currently represents the adjacent 2nd District. Rather than run against the long-serving and popular Scott, Luria has a couple of options. Reportedly, she owns a condo in Virginia Beach, which is in the 2nd District. Alternatively, she could choose to keep her current residence and still run in the 2nd, joining Spanberger and Griffith in running in districts in which they do not live. The new 2nd District contains a lot of the territory she currently represents and, like the current district, is considered a toss-up, albeit with a slight Democratic lean.

Overall, the special masters project that the partisan divide has not been altered as a result of the various changes. Generally, they predict, Democrats should enjoy a 6-5 split, with Republicans achieving a 6-5 advantage in very good Republican years and Democrats returning to the current 7-4 split in very good Democratic years. The Virginia Public Access Project (VPAP), using a different measure, views the partisan split a little more evenly, with both parties having 5 strong or moderate leaning districts, with one toss-up district.

State Senate

Most of the changes to the Senate map were slight, primarily designed to keep together communities of interest.

Two changes did have significant impacts. First, the special masters altered district boundaries in Northern Virginia to create a district entirely within Arlington County. That change set off a chain reaction of changes to the boundaries of other districts in the area.

Although the special masters did not consider it major, a change to the boundaries of the 25th and 26th districts “to improve compactness and to accommodate a reasonable request to keep the Northern Neck intact” had a significant political impact. It resulted in altering the pairing of incumbents in the region. Instead of being paired with Richard Stuart (R), Ryan McDougle (R) of Hanover County will be paired with Tommy Norment (R) of James City County. Norment, of course, is the long-time Republican Senate floor leader and is also a mentor of McDougle. That should be an interesting primary.

The number of paired incumbents remains the same as it was with the original map: 10 Democats and 10 Republicans. With the exception of McDougle/Norment, the pairings are the same. Perhaps Norment will elect to retire, as Saslaw, Howell, and Newman indicated they would do, even before the redistricting maps were out. The only other notable aspect of the pairing of incumbents is the continued pairing of two Black Democrats, Lucas and Spruill, in the Hampton Roads area. For a list of all the incumbents affected, see the table below.

As far as the overall partisanship of the map is concerned, the special masters feel the map “still suggests a marginal Democratic advantage.” Using a different base for its measurement, VPAP agrees. Under the current Senate map, it rates 21 districts as strongly or moderately Democratic, 17 as strongly or moderately Republican, with 2 tossup districts. In contrast, the new map would gain a strong Democratic district for a total of 22 strong or moderate Democratic seats. The Republicans would still have 17 strong or moderate districts and there would be one toss-up district.

House of Delegates

There were lots of minor changes in House districts, primarily to accommodate comments received and to better represent communities of interest. The most significant change was in Northern Virginia, in which Falls Church was placed with Fairfax County, rather than Arlington County. That move set off a “cascade of changes throughout the area.”

As a result of the changes, there is one fewer pairing of incumbents, with 44 incumbents affected, instead of 46, as in the original map. The reduction of pairings occurs in Northern Virginia and the remaining pairings are scrambled, with different pairs being put in the same district. The final list of incumbents affected is shown in the table below. (To compare this list with the earlier list, see here.)

The supreme ironic result of the redistricting process is the pairing of delegates Schuyler VanValkenburg (D) and Lamont Bagby in the 80th House District in Henrico County. VanValkenburg was the patron of the constitutional amendment that took the redistricting process away from the General Assembly and placed it with a commission and, ultimately, the Supreme Court. He was one of the strongest supporters of the amendment, although a majority of his Democratic colleagues opposed it. Bagby is the chair of the Virginia Legislative Black Caucus and was one of the most vocal opponents of the amendment. VanValkenburg must have thought of the cynical saying, “No good deed goes unpunished.”

Coming in second in ironic results is the pairing of Delegates Simon and Ransone and of Senator McDougle with members of their own party in the same district. All three were members of the Virginia Redistricting Commission and could have prevented such results if they had reached a bipartisan compromise on the General Assembly maps.

Overall, the special masters say that their analysis “suggests a small Republican advantage in the House of Delegates.” On other hand, VPAP’s analysis shows a slight Democratic advantage in the House. (Neither analysis factored in the results of the 2021 House election.)

What’s Next

The redistricting in Virginia is complete. In accordance with the provisions of the state constitution, the maps produced by the Supreme Court are final. There is no avenue of appeal to the courts, at least not in state courts. In its order issued with the release of the maps, the Supreme Court declared, unanimously and conclusively, that “the Final Redistricting Maps prepared by the Special Masters are fully compliant with constitutional and statutory law applied, as the Court directed, in an apolitical and nonpartisan manner.”

The only question still looming is when Delegates will have to run in the new districts—fall of 2022 or fall of 2023, when their normal two-year terms would require them to run. Paul Goldman, a Richmond lawyer and former chairman of the state Democratic Party. has filed suit in federal court, arguing that, under the “one-man, one-vote” principle, the state must hold elections for the House of Delegates in 2022 under the new districts. A three-judge panel has been appointed to hear the case, but it is not clear when it will be heard.

Immediately pending is a special election in Norfolk on January 11 to fill the seat vacated by Delegate Jay Jones. In its final order, the Supreme Court left it up to the State Board of Elections and the Department of Elections to decide whether to use the old district lines for that election or the new ones. Given the time frame involved, it is presumed that the old district lines will be used.

In the meantime, the scrambling and speculation has begun.

My Soap Box

Although the manner in which it was reached was probably not anticipated, the voters of Virginia got what they desired when they adopted the constitutional amendment: non-gerrymandered, nonpartisan redistricting, in which the public played an active role. It is unfortunate that most of the other states are not following the example of the Commonwealth.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.