There are many layers to the dysfunction of America’s (and Virginia’s) health care system. I have written frequently about price opacity, the inability of consumers to compare medical services by price. Prices are essential to a market-based economy. Indeed, one could say that without prices, it is impossible to have a market-based economy. I’m not sure how you’d label the system we do have — there’s too much private ownership to call it socialism. But whatever it is, it sure as hell isn’t a market-based system.

The question I continually ask is why. Why is there no price transparency? Part of the problem is the convoluted system in which hospital charges bear no relationship whatsoever the cost of providing the service. Hospitals post charges. Government programs (Medicare and Medicaid) and insurance companies negotiate the posted charges to a lower level. And consumers pay some residue of those lower charges based upon how generous their insurance plans are. I chronicled my own experience with price opacity in the Richmond health care market when I elected to undergo hip-replacement surgery. (See “One Man’s Descent into Healthcare Price Opacity.“)

A recent Wall Street Journal article suggests that the dysfunction is so extreme that hospitals themselves often don’t know how much it costs to perform a routine, commoditized procedure such as knee replacement surgery.

The article highlights a rare instance in which a hospital, the Gunderson Health System’s hospital in La Crosse, Wis., undertook a study to find out how much it cost to conduct a knee replacement surgery. The hospital had been routinely jacking up its charges by about 3% a year, reaching a list price of $50,000 by 2016. But no one knew how much it actually cost to do the surgery. After a detailed, 18-month review, the hospital concluded it cost at most $10,500 — including the physicians.

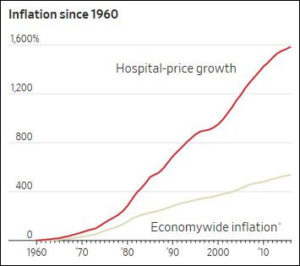

Thus, another part of the answer to my question is the failure in hospital accounting. Hospital charges are largely unrelated to cost because the hospitals themselves often don’t know what procedures cost. If hospitals don’t know what routine procedures cost, how can they make rational business decisions? How can they exercise cost controls? No wonder health care costs go nowhere but up.

Writes the Journal:

Hospitals can be shielded from the competition that forces other industries to wring out expenses and slash prices. Hospital list prices are a starting point for negotiations with insurance companies over what they will actually pay, and those deals are confidential. Consolidation has given hospitals greater pricing power in many markets, according to health-economics researchers.

“Being cost effective was not an imperative in that type of market dynamic,” said Derek Haas, chief executive officer of Avant-garde Health, a health-care cost and quality analytics company that worked with Gundersen. …

For consumers, the prices paid for the surgery at some hospitals in the U.S. were more than double the prices at others, according to an analysis of 88 million privately insured people to be published in the Quarterly Journal of Economics.

In a market economy, competition would work to drive down the price of elective surgical procedures. If Hospital A charges an excessive price for knee replacement surgeries, orthopedic physician’s practices or a competing hospitals could enter the marketplace, charge less, and gain market share. But here in Virginia, hospitals have consolidated into massive health care systems, and they have shut down competition through Certificate of Public Need regulation. Regulations restrict entry of newcomers into the medical marketplace, thus conferring monopoly-like protections on hospitals. Virginia hospitals are not compelled to drive down costs and reduce charges to stay in business. They just ratchet up their charges each year, immune to pressures from the marketplace.

So, what is Virginia’s political class doing about this? Basically, nothing. Rather than address the core issues of competition and price transparency, the political class is focused on doing what it knows how to do, which is rob Peter to pay Paul — in other words to redistribute wealth. Thus, the public policy debate in Virginia focuses on Medicaid expansion and who pays for it. Meanwhile, costs for everyone, rich and poor and in-between, continue to rise with no end in sight.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.