by James A. Bacon

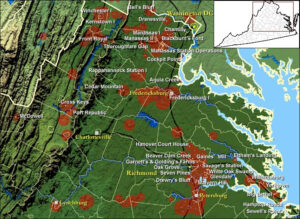

Culpeper County prohibits construction of solar farms on Civil War battlefields. Now a proposal under consideration by the Board of Supervisors would discourage large solar projects adjacent to battlefield land held in historic easement, reports the Culpeper Star-Exponent. And that restriction is just one of many changes to the county’s Utility Scale Solar Facility Development Policy under review by the board.

Last year the board approved the 1,000-acre Greenwood Solar project over local opposition. Since then resistance to the land-consuming facilities has gotten more organized. One group, Citizens for Responsible Solar, has actively pursued a policy of delay and encumber to restrict development of large-scale solar farms. Last month Cricket Solar pulled a proposal for a 1,600-acre solar farm in the county. Meanwhile, local opposition has stalled progress on utility-scale projects in other counties.

On the state level, it is the policy of the Northam administration, the General Assembly, the environmental community, and Dominion Energy to boost the contribution of solar power to Virginia’s energy mix. People may disagree about how far and how fast to go, but just about everyone agrees on the desirability of having more solar than we have now. But opposition at the local level has emerged as a significant barrier to large-scale deployment of solar.

The changes under review by the Culpeper board show the wide range of restrictions that are possible. Only a few of the items appear gratuitous. Most purport to address real concerns. But if adopted en mass, they could severely restrict utility-scale solar in Virginia. Staff-suggested changes include:

- Limit total solar project development in Culpeper to 2,400 acres. (The board declined to enact this change earlier this year when it came up for a vote.)

- Limit individual solar panel installations to 300 acres.

- Prohibit the owner of a conditional use permit from selling it to a third party without board approval. (The business model of many developers is to develop the project then sell it to a third party.)

- Revoke conditional use permits if inactive for more than 12 months.

- Encourage recycling of solar panels upon decommissioning.

- Limit solar plant construction activity from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m. (compared to 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. now).

- Require historic properties and resources to be screened.

- Prohibit the storage of solar power batteries on site.

- Require fencing to be placed behind perimeter landscaping.

- Require a lighting plan and limit maximum height of panels to 12 feet.

- Require an erosion-and-sediment control plan and require a stormwater management permit from the state Department of Environmental Quality.

- Require a vegetative management plan.

- Require the hiring of local contractors and the holding of at least two job fairs.

Other proposed regulations, says the Star-Exponent, address road repair, solar panel specifications, and making available information about the physical and chemical properties of solar panels.

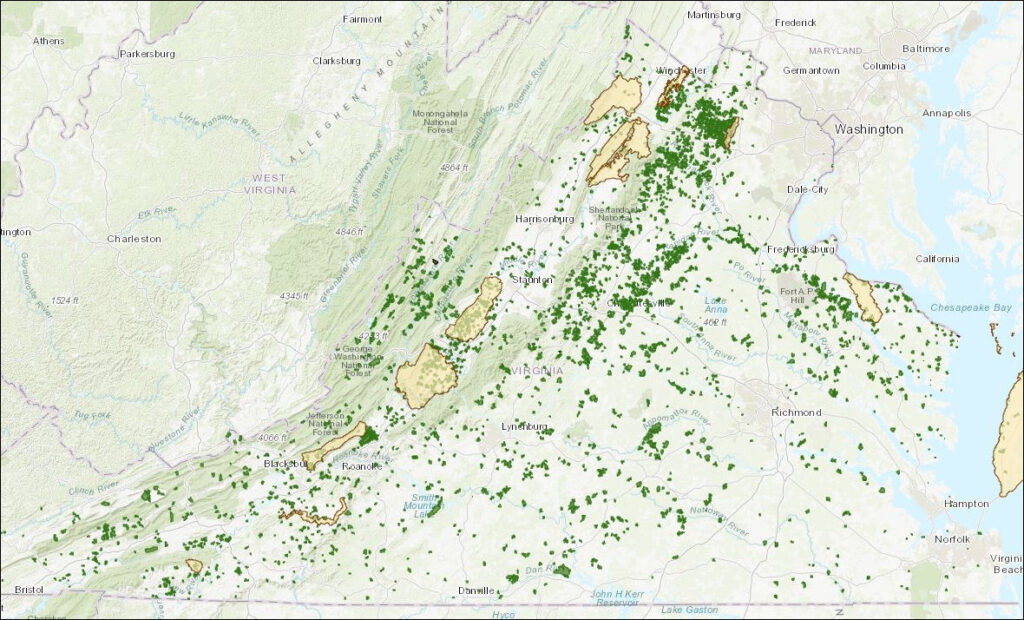

Bacon’s bottom line: It is not feasible to plop down a solar farm just anywhere. Solar facilities must be located near electric transmission lines, the land must be inexpensive, and parcels must be available for sale. The more locations that are excluded by conservation easements, national forests, historic and cultural heritage sites, Civil War battlefields and the like, the more difficult it becomes to find economically justifiable locations. Adding a panoply of local land-use regulations piles on additional costs, effectively ruling out even more locations.

The demand for renewable energy is strongest in Northern Virginia, location of the world’s largest cluster of data centers, most of which are owned by corporations pledged to move to a 100% renewable electricity supply. Ironically, anti-solar farm sentiment and development restrictions are greatest in the rural outskirts of Northern Virginia — in places like Culpeper County — where locals have battling suburban sprawl and fighting to preserve their way of life for decades.

Ordinary Joes like me want to see more solar because it’s clean and, when suitable sites can be found, it’s economical. But for Virginia environmentalists, the crusade for solar is bound up with the angst over global warming. Solar is not just desirable, it is a moral necessity. Perhaps I’ve overlooked something, but it seems like environmentalists are largely AWOL from the land-use debate playing out in Virginia’s rural counties. The legislative focus of the environmental lobby has been on circumventing Dominion Energy’s retail monopoly to enable more community solar. That may be a worthy goal, but it amounts to squabbling over dimes and ignoring the dollars.

If Virginia wants more solar power, it needs to reconcile the conflict between large-scale solar farms and the sensitivities of impacted populations. I don’t see any of our elected officials leading that effort.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.