by James A. Bacon

I have often advanced a common-sense proposition: If you want to create more affordable housing, increase the supply of housing. If the housing stock increases faster than demand, the price declines. A new study on “inclusive housing” policies in the Washington-Baltimore metropolitan area, which includes Northern Virginia, gives some support to that proposition, although it suggests that in highly regulated housing markets, the relationship between supply, demand and price is not straightforward.

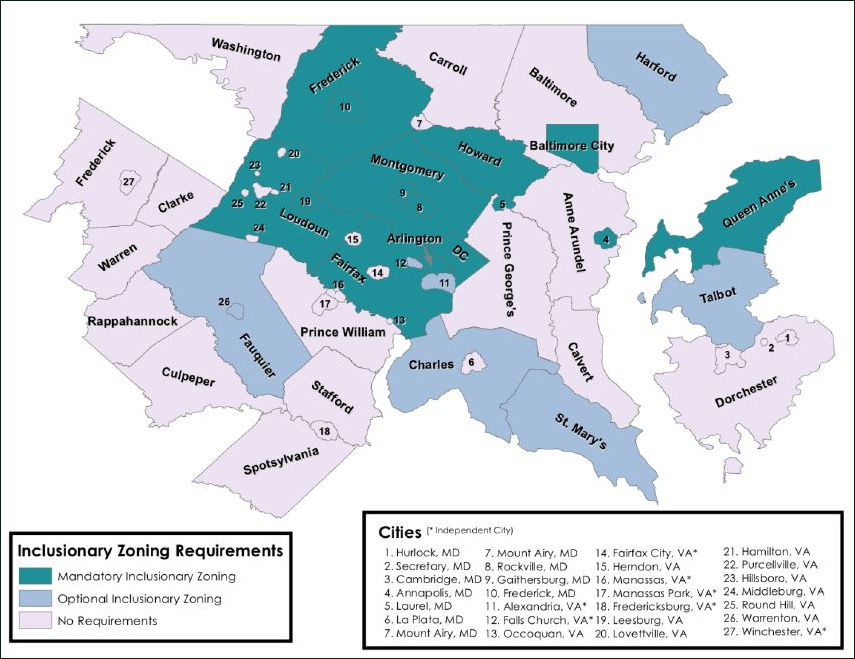

Emily Hamilton, a research fellow at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, has undertaken an in-depth study of inclusionary zoning in the Washington-Baltimore metro. Inclusionary zoning (IZ) is a policy in which local governments require or incentivize real estate developers to provide below-market-rate houses in new housing developments.

Economic theory (which has informed my thinking on this blog) predicts that IZ could be counter-productive. By increasing the cost of building new units, the policy diminishes the supply of new housing, which has the effect of pushing housing prices higher overall. But IZ programs vary widely in design and impacts vary, says Hamilton in her paper, “Inclusionary Zoning and Housing Market Outcomes.”

Hamilton contrasts inclusionary zoning with exclusionary zoning such as minimum lot-size requirements, bans on multifamily housing, and other rules that limit housing supply. She also draws a distinction between mandatory policies, in which developers are required to provide a portion of below market-rate units in new housing developments and optional policies that give developers incentives to provide subsidized units in exchange for density bonuses. The broad conclusions from a Mercatus Center summary:

- Mandatory inclusionary zoning is associated with an increase in house prices. Hamilton concludes that mandatory inclusionary zoning in the Baltimore-Washington region has increased prices by about 1 percent for each year that the program has been in place in the jurisdictions that have adopted it.

- Mandatory inclusionary zoning is not associated with a decrease in new housing construction in the Baltimore-Washington region. While other studies have identified a decrease in new housing supply with the implementation of inclusionary zoning, this study finds no evidence that inclusionary zoning has reduced the number of new building permits.

- Optional inclusionary zoning programs may not offset developers’ costs of providing subsidized housing. Most optional programs in the Baltimore-Washington region have been unsuccessful in producing affordable units. This indicates that the value of the programs’ density bonuses do not outweigh the cost to developers of providing subsidized units. The exceptions are Alexandria, VA, and Falls Church, VA, where underlying exclusionary zoning makes density bonuses very valuable.

The first two findings seem to contradict one another. How is it possible that inclusionary policies have not diminished the supply of new-dwelling construction yet simultaneously have driven up housing prices?

Whatever the case, the analysis gets exceedingly complicated. Every jurisdiction has a different spin on IZ — Alexandria, for instance, not only provides density bonuses for developers but reduces mandated parking minimums, which other jurisdictions do not do — so it is difficult to isolate the effect of any one variable. Moreover, Hamilton found it difficult collecting data on the number of IZ units produced for more than 50 jurisdictions in the Washington metro, so data quality may be an issue as well.

Critically, Hamilton gives insufficient attention to a critical consideration — the interaction between inclusionary and exclusionary zoning policies. Almost every Washington-area locality adopted exclusionary policies restricting supply for decades before it adopted inclusionary policies. Indeed, it was the effect of exclusionary policies on restricting supply and driving up housing prices that created an affordability crisis in the first place. But rather than repeal or modify their exclusionary policies, local governments added inclusionary policies s another layer of regulations.

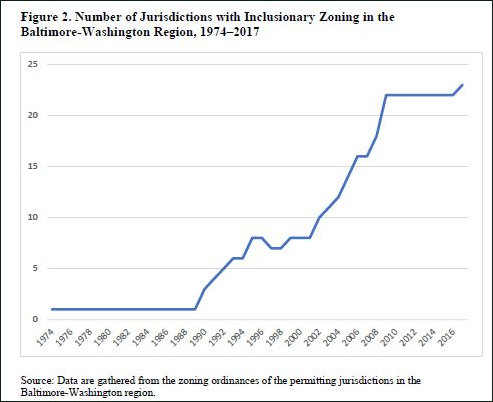

Be that as it may, the study provides some useful information. The following graph shows, for instance, the spread of inclusionary zoning policies among jurisdictions in the Washington-Baltimore region.

The spread of inclusionary policies has coincided with a steep rise in metro Washington real estate prices. Clearly, the policies have been inadequate to the task of making housing more affordable for lower-income residents.

Perhaps an even more useful graph would chart the spread of exclusionary policies beginning in the 1950s and 1960s that created the affordability crisis in the first place. Even better would be a graph showing the two sets of regulations working in tandem, correlating the proliferation of zoning rules generally with housing price increases.

I commend Hamilton for acknowledging the limits of her data and her reluctance to draw sweeping conclusions. She is doing important work and, as far as I know, she’s the only person doing it. I hope she sticks to it. If we don’t understand the causes of the affordable housing crisis, we will never solve it.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.