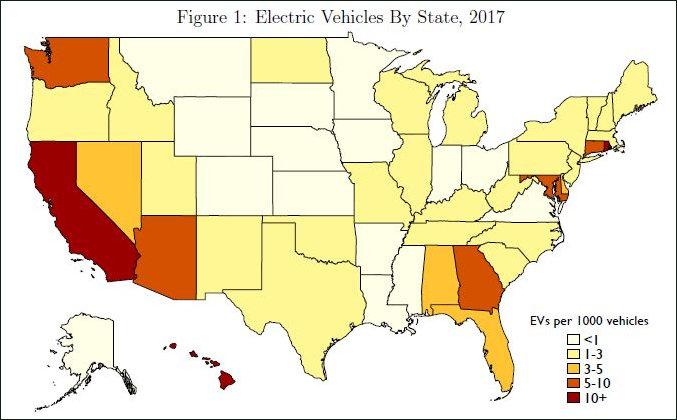

Electric vehicles (EVs) are commonly touted as a necessary part of America’s green energy future: Shifting from cars powered by gasoline-combustion to cars powered by 100% clean electricity will cut CO2 emissions (and other pollutants) implicated in global warming. Virginia ranks among the states with the lowest EV market share. But on the assumption that EVs eventually will become part of Virginia’s energy future, there’s no time like the present to start thinking about what EV taxation should look like.

Perhaps the most pressing issue is whether to tax EVs the same as conventional cars for the purpose of raising money to pay for the construction and maintenance of roads, highways and bridges. EVs contribute to traffic congestion and cause traffic accidents like any other kind of car. Should their owners not share in the cost of building, maintaining and operating roads?

The rise of EVs, hybrids and high miles-per-gallons vehicles was part of the justification when Virginia overhauled its transportation tax structure during the McDonnell administration. Revenues from the gasoline tax were stagnating, and legislators saw a need to diversify the source of transportation revenues. Once the tax increases were enacted, however, cogitation about the tax structure largely ceased.

Virginia cannot ignore the problem forever. One good place to start thinking about the issue of EVs and road maintenance is a new paper by two University of California professors, Lucas W. Davis and James M. Sallee, “Should Electric Vehicle Drivers Pay a Mileage Tax?” The paper explores the many trade-offs involved.

The issues are not straightforward because automobiles of all kinds have what economists call externalities, that is, they have social costs that are not reflected in the price charged for fueling and operating them. Vehicles of all kinds need roads and bridges to drive on. They also need police and rescue units to enforce traffic laws and clear accidents. They also generate pollution.

Analysis is made more complicated by the fact that the social cost of congestion varies by location and time. Driving a car northbound at 7:30 a.m. on Interstate 95 in Prince William County will create a higher social cost than, say, driving a car at 10:30 a.m. on Route 460 outside of Farmville.

Another complication is that while conventional cars emit CO2 at the tailpipe, EVs effectively emit CO2 at the electric plant, and some power companies are more carbon intensive than others. Thus, driving a car in a territory served by a coal-intensive generation fleet could generate more CO2 than in a territory with lots of nuclear, solar and wind power — and conceivably more than a car with a highly efficient internal combustion engine.

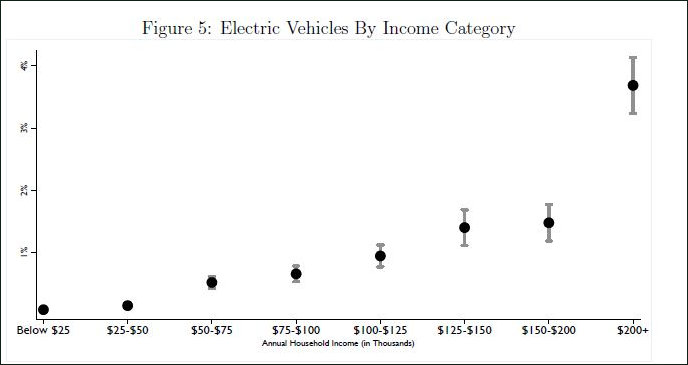

Then there’s the reality that EV subsidies are a form of reverse income redistribution. EVs qualify for federal tax credits valued at $2,500 to $7,500 per car. Who captures these subsidies? Wealthy people. As Davis and Sallee write, “Electric vehicles as a percentage of all vehicles increases from close to 0% for annual incomes below $25,000, to 1% for annual incomes $75,000-$125,000, to 4% for annual incomes above $200,000. Likewise, the structure of local taxation — taxing gasoline sales rather than charging on a mileage-driven basis — equates to a benefit of about $300 per year, the authors calculate.

Bacon’s bottom line. What would be a rational state/local tax structure for EVs in Virginia? Here are some principles to guide the formulation of tax policy.

- User pays + externalities. To the greatest extent possible, transportation should be a user-pays system — but a system in which the user pays not only for visible costs but externalities.

- Construction, O&M, congestion. A rational funding system would distinguish between three sets of road and highway costs: the cost of building new capacity, the cost of maintaining and operating the roads, and the cost of driving during periods of peak congestion.

- EVs should pay, too. EV drivers should pay their fair share of building new roads, maintaining and operating those roads, and the cost (externality) they impose on other motorists for contributing to congested driving conditions.

- Pollution externalities. Cars of all kinds should pay some kind of tax/user fee that reflects the social cost of the pollution they generate, primarily Nitrogen Oxide, a contributor to low-level ozone, and CO2, a contributor to global warming. Ideally, they should pay in direct proportion to the amount of pollution they cause.

Conceptually, I think that’s pretty clean. The really big sticking point I foresee is calculating the social cost of CO2 emissions. No one, not even the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), knows the social cost of CO2. No one knows for sure how fast global temperatures are increasing, no one knows for sure what negative costs will come from higher temperatures, and no one knows for sure what offsetting beneficial impacts will come from a warmer climate. Inevitably, any calculation of the social cost will be driven by untestable and unproven assumptions, and by what factors are included and excluded from the calculation.

That messy question aside, an ideal scheme would adjust for both direct CO2 emissions from gasoline combustion and indirect emissions via the electric grid. Any such calculations would have to be revisited periodically to reflect the steady greening of the grid over the next few decades.

It’s fun to think about the ideal system of taxation. But is an ideal system economically feasible? That depends largely on the cost of administering the system. And is it politically feasible? There are so many winners and losers that fundamental change will be difficult. But we won’t know until we start the conversation.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.