Who possibly could have predicted this? After years of “racial equity” and “restorative justice” disciplinary policies in Virginia school districts, discipline in schools has gotten worse, at least as measured by the number of disorderly conduct charges filed by school resource officers.

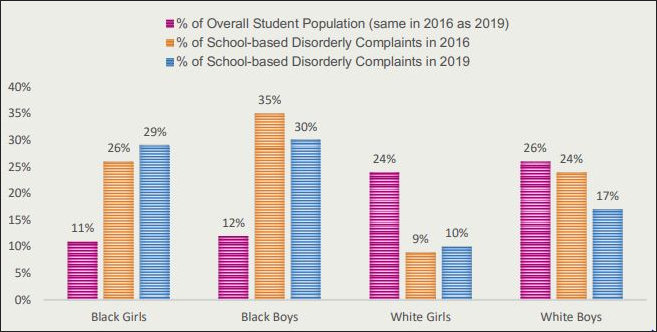

The number of disorderly cases filed increased from 360 in 2016 to 523 this fiscal year, a four-year increase of 45%, reports the Virginia Mercury, citing data from a report by the Legal Aid Justice Center. Black students, representing 22% of the state’s school population, account for 62% of the complaints. Charges against black girls have increased in “startling” numbers, the study observes.

The Legal Aid Justice Center’s proffered solution? Rewrite the disorderly conduct law to “stop criminalizing childhood behavior and unnecessarily pushing youth into our criminal legal system.”

Despite the imposition of therapeutic disciplinary policies designed explicitly to reduce the black-white gap in in-school arrests, out-of-school suspensions and in-school suspensions, the gap is as vast as ever. Logically, one might conclude from this data that these ideologically driven policies are not working and it’s time to re-evaluate them. But there is no sign of such a reappraisal in the Legal Aid Justice Center’s report. To the contrary, the proffered solution is to deprive teachers and administrators of another tool for maintaining order in schools.

My prediction: Adopting the Legal Aid Justice Center’s proposal would double down on a failed policy and magnify the failure. School discipline will not improve. Disorderly behavior will spread, and the racial gap in educational achievement might even get worse.

What the study says. The report, “Decriminalizing Childhood: Ending School-Based Arrest for Disorderly Conduct,” maintains that Virginia’s disorderly conduct statute is a “vague, overbroad, catch-all law that criminalizes low-level public disruption that does not rise to the level of physical harm, property damage, or even a threat.” The report then ties the law to Virginia’s racist past.

Disorderly conduct laws find their strongest roots in the insidious “vagrancy” and other public order laws that fueled policing in the Jim Crow South. Intentionally designed to be vague in order to facilitate discriminatory enforcement, these laws have been used to control the movement of Black people, break up strikes and protests, and target suspects when no probably cause exists — a shameful legacy Virginia has not yet left behind.”

[Since 1990] students can be adjudicated delinquent (found guilty of disorderly conduct in Virginia if they either intentionally or recklessly create a risk of “public inconvenience, annoyance, or alarm” by creating a disruption that “prevents or interferes with the orderly conduct” of any school or school-sponsored operation or activity.

Black students in particular, and Black girls at a momentously increasing rate, are targeted in school with disorderly conduct criminal charges in disproportionate numbers to their white peers. And the consequences of such charges, whether they proceed before a judge or not, cause cumulative harm that can derail a child’s education and make them more likely to sink deeper into the justice system.

The Justice Center says that children have been charged for:

- Singing a rap son on a school bus;

- Running and shouting in a cafeteria;

- Cutting in a lunch line;

- Pushing past a teacher to get onto a school bus;

- Yelling or cursing at other students or teachers; and

- “Flailing” as a result of a schedule change that was difficult for the student to process because of a mental health condition.

Over the past five years, 19% of all disorderly conduct charges against young people in Virginia were filed against children age 13 years or young. In one 2014 example, an 11-year-old, sixth grade boy with autism was arrested at school and charged with Disorderly Conduct for kicking over a trash can in a school hallway.

Bacon’s bottom line. Let me preface my criticisms of this report with an observation that no disciplinary system is perfect, and all laws should be periodically scrutinized and re-evaluated. People are human, and it would surprise no one if in the 2,000 or so cases filed over the past five years one couldn’t cite examples of unjustified complaints, as the Legal Aid Justice Center has done.

However, the Justice Center clearly is highlighting instances that best make their case. Are they typical? What do some of the worst instances of disorderly behavior look like? Would most people agree that application of the disorderly conduct law in such cases was entirely appropriate? We can’t tell from the Justice Center report. But eliminating the law, as opposed to reforming it, based on a handful of cherry-picked cases makes no sense.

Further, the report takes the standard racial bean-counting approach to the school disciplinary issue, breaking down the number of disorderly charges by sex and race, and making the assumption that any discrepancy represents an injustice. But what if the punishments reflect the reality that black students are more disorderly than other students? The report makes no effort whatsoever to adjust for poverty, disability, family structure, geography, or disciplinary history. Are the disciplined children more likely to be poor? Are they more likely to come from single-parent households? Are they more likely to suffer disabilities? Are they more likely to be concentrated in inner-city schools? Are they more likely to have accumulated more disciplinary complaints of other kinds? Racism and/or discrimination is assumed, not documented.

One more observation. The Justice Center report does not ask why the number of disorderly conduct charges has increased so dramatically despite a concerted effort by state and local educational authorities to reduce their number. To all appearances, social-justice policies are producing exactly the opposite result they intend.

Let me suggest a hypothesis to explain what might be going on. I don’t know this to be true, although it is consistent with anecdotal information I have seen and heard, but I think it is far more plausible than the idea that teachers and administrators have suddenly gotten more racist in the application of the disorderly-conduct law over the past five years.

- The less punitive “restorative justice” approach is not working.

- Students generally have figured out that poor behavior has fewer consequences.

- Black students have figured out that teachers and administrators, intent upon reducing the black-white discipline gap, are willing to cut them even more slack.

- Disorderly behavior has gotten worse. The spreading disorder may not be reflected in numbers reported to school districts and the state, however, because teachers and administrators have every incentive to suppress them.

- As disorderly behavior has gotten worse, so has the number of more extreme instances that fully justify disorderly-behavior complaints. Thus, the number of complaints has increased.

If my conjecture is accurate, the “progressives” running Virginia’s schools are hopelessly misdiagnosing the problem, their so-called solutions will continue to contribute to the erosion of order in schools, and the quality of education will continue to decline. Those most hurt will be blacks and minorities — victims of another unintended consequence.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.