In September 0f 1810, a slave named Joe disobeyed an order given by his overseer, David Elmore, on the Henrico County plantation of Thomas H. Prosser. The overseer endeavored to “correct” Joe, and Joe responded by attacking him with a pole ax. A fight ensued. According to a coroner’s report filed after the incident, “the said Elmore did give the said Negro man Joe a mortal blow about the body.”

Joe did not die immediately, however. Prosser summoned a doctor, John H. Foushee, to give his slave medical attention. Foushee gave the following account of Joe’s final hours:

When I saw him he complained of great soreness in a part which seemed on inspection not materially injured. After the Effect of medicine, he obtained quiet as I was informed by the attending servant. On Saturday I heard that Joe was much better, and did not think it necessary to visit him, as his general soreness appeared then to be his only complaint, until late in the afternoon I was hastily called to him, the messenger informing me that Joe was much worse. I walked immediately with Mr. Prosser and found he had expired.

Little is known of Joe’s life, but the circumstances of his demise were recorded in a Henrico County coroner’s report, which in turn was collected by the Library of Virginia and placed in its digital collections.

It is commonly thought that the historical record tells us little about the lives of slaves, and it is true that very few left memoirs or letters. But incidents in their lives (and deaths) were captured in a host of legal records preserved in county courthouses – bills of sale, deeds of emancipation, Free Negro registrations, Freedmen’s contracts, freedom suits, petitions for re-enslavement and many other types of documents. The Library of Virginia has captured these hand-written records, transcribed them, and stored them in a searchable database as part of its “Virginia Untold” initiative.

The Library’s work has been years in the making, but it seems especially relevant since the unveiling last year of the New York Times‘ 1619 project, which reinterprets American history through the lens of slavery and race. In the Times‘ telling, 1619, the year in which African slaves first set foot in an English colony in the North American mainland, should be seen as the true founding date of America. The 1619 narrative sees the nation’s history as a ceaseless, 400-year-long story of oppression. The Times project has inspired a vigorous counter narrative by scholars who acknowledge the horrors of slavery and injustices of the Jim Crow era but view American history since 1776 as a largely successful struggle to implement the ideals of the American Revolution for everyone.

As with everything else in American society today, the interpretation of history has become highly politicized. Those of a leftist persuasion embrace the New York Times view of American history as hopelessly stained and the origins of our core institutions as illegitimate. Emphasizing the extraordinary progress that has been made, other commentators highlight how the Revolutionary ideals — that everyone has the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness — drove history forward.

The Library of Virginia’s “Virginia Untold” project makes the raw material of history accessible to all Virginians. Anyone can access the underlying documentary evidence and see for themselves what life was like. One of the most fascinating data sets includes the coroner’s reports, formal inquiries into the deaths of Virginians, including slaves.

The coroner’s reports provide vivid glimpses into the world of Virginia slavery from the late 18th century to the end of the slave era in 1865. It shows the brutality and mistreatment of slaves through a series of vignettes that have otherwise been lost to history. At the same time, it portrays a more complex and nuanced picture than is commonly acknowedged. For instance, as in Joe’s case, slaves did not always suffer blows meekly. Sometimes they resisted their mistreatment. Some slaves murdered other slaves in quarrels, and others fell victim to workplace accidents. Some died by their own hand, and infants were slain by their mothers – what we might call today “deaths of despair.” With surprising frequency, slaves expired from drunkenness, passing out, and exposure to the cold.

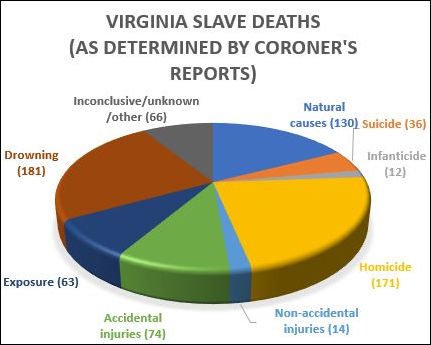

The chart atop this post provides a breakdown of the categories of slave deaths recorded in 747 coroner’s reports. Greg Crawford with the Library of Virginia describes the courthouse documentation as “fairly exhaustive,” although he concedes that stray records may have been overlooked. He also warns that they don’t encompass all violent slave deaths, only those that required a ruling by a coroner regarding the cause.

Drownings were the largest category – slaves drowned with startling frequency, and no more so than in Henrico County, where they frequently engaged in commercial, artisanal and industrial occupations. Working around the river docks and canal locks was a treacherous endeavor.

In 1831 Phil, a slave belonging to William Waddel in Chesterfield County, “Accidentally drowned in James River by falling from a lighter belonging to French and Jordan of Richmond.” In 1823 a slave named Billy Branch was killed “by an accidental fall from the bank of the James River Canal, while engaged in a scuffle or fight with a slave named Shadrach.” And in 1835, the slave Billy Butler “died by accidentally drowning while aiding and assisting in over-turning a boat at the Old Locks on the James River Canal.” Others drowned while swimming, fishing, or accidentally falling into the water.

Many slaves examined by coroners were found to have died of natural causes – “died by the visitation of god in a natural way” was the standard phrase. Occasionally, coroners would note the circumstances of the death. In 1848, it is recorded that a Henrico slave, Reuben Ward, died “during religious worship.” A Lunenberg County slave named Tom died in 1816 in “a natural way” while “being committed to jail for a felony.”

Other reports testified to lives of despair. Various slaves in Chesterfield and Henrico counties were ruled to have taken their own lives. A slave named Sarah was found “alone in a kitchen with certain leather strings which she put around her neck, tied the same so tight as to suffocate herself and cause her own death.” Abraham, a slave of William Pemberton, “being moved and seduced by the instigation of the Devil, died when he hung himself with a rope by the neck from a dogwood tree.” Other slaves in the Richmond area cut their own throats or hurled themselves into the James River.

Perhaps most tragic were cases in which mothers killed their own children. An unnamed Henrico child “was killed and murdered by its mother, Kesiah, by smothering or by stopping its breath by putting her hand on its face and keeping it there until it was dead. Kesiah did not have God before her eyes, but [was] moved and seduced by the instigation of the Devil.” Even more gruesome, an unnamed female mulatto child was “feloniously killed and murdered by her own mother, Fanny, with blows to the face and head made with a brick.” The victims of some infanticides, speculates the Library of Virginia’s Crawford, might have been the offspring of coerced unions between slave and master.

Coroners examined slaves who died from beatings and abuse at the hands of owners and overseers. Polima, a Goochland slave, “died from severe, unmerciful and inhuman treatment and wounds inflicted by her owner, William T Fletcher.” Another by the name of Jeny, “died from the whipping given her by William Tuggle.”

Slaves had access to alcohol, and like whites, often drank to excess. Drinking frequently led to death by exposure during cold weather. A Henrico slave by the name of Jack Robinson died in January 1805. The coroner described his demise this way: “Died naturally by freezing to death in a field where he had stopped, being overcome with drink and from the severity and inclemency of the weather.” Another slave, Robert, “Died from exposure from the cold, wetness of the ground and from the liquor drink.”

Many slave deaths were classified as homicide. Often these killings were the result of altercations with owners, overseers or other whites. But slaves also argued amongst themselves and with free blacks. A coroner’s report captures one such incident in considerable detail.

In 1841 Spencer, a Negro slave who was the property of Chastaine Porter of Powhatan County, died in a fight with another of Porter’s slaves, Reuben. The two men were working on a boat on the James River & Kanawha Canal. John, a boy slave who was the property of Mrs. Sarah Sowell of Essex County, gave the following testimony:

The witness says [he] was standing on the tow path of the Canal when Spencer & Reuben commenced quarrelling and that Reuben picked up a boat pole jumped on the tow path. Spencer came up to the head of the boat & then Reuben raised the pole and struck at Spencer but missed him. He immediately raised the pole again & struck Spencer & knocked him from the head down on the boat. After he had fallen Reuben [got] up with the pole again & struck at Spencer or in this direction & at the same time let go the pole which fell in the boat.

The witness then leaped on the boat and saw Spencer lying down. [He] called Mr. P. Roach who was in the cabin of the boat & said that Spencer was dead. Reuben then reached on the boat and got a pole and with an oath said he would give him some too. He then ran to the cabin where Mr. P. Roach was.

Roach corroborated the slave boy’s testimony:

The witness was coming from Richmond on the boat with Spencer, Reuben & John – at the Lock No 2. Spencer the headman ordered Reuben to cut the head of the boat from the bank. From this the two commenced quarrelling & Spencer said to Reuben unless he would attend to his business he should not come in the cabin. Reuben then threatned to strike Spencer with the boat pole. Spencer then walked up towards the head of the boat & witness heard the pole strike the boat. In few moments John came running to the cabin where witness was & said that Reuben had killed Spencer & had threatned him. Witness, went immediately up from the cabin and examined Spencer & found him dead. Reuben acknowledg to witness that he struck Spencer but did not intend to kill him

Poring through these records creates the impression that slave life in 19th-century Virginia was one of unremitting brutality and despair. But remember, Virginia’s African-American population ranged from roughly 300,000 in 1790 to 500,000 in 1860, and the Library of Virginia database collected reports over a 100-year period. While there may be missing records, and while not all violent deaths were recorded by coroners, the incidence of homicide, suicide, and fatal injury may have been no more common among slaves than among Virginians living today — most likely less. More research needs to be done to determine how accurately the stories contained within these records reflect the routine reality of slavery.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.