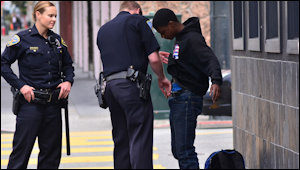

Citing Charlottesville Police Department data, the Cavalier Daily, the University of Virginia’s student newspaper, has found that African-Americans are stopped and frisked at a rate nine times greater than whites.

Citing Charlottesville Police Department data, the Cavalier Daily, the University of Virginia’s student newspaper, has found that African-Americans are stopped and frisked at a rate nine times greater than whites.

The statistical report from the 2017 calendar year detailed that of the 173 total recorded stop incidents, 70 percent of the individuals were black. Of the 125 stop incidents with search-and-frisk, 91 of the individuals — or 73 percent — were black. According to 2016 estimates of Charlottesville demographics, only 19 percent of the City identifies as black or African American.

Predictably, Bill Farrar, director of strategic communications for the Virginia chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union, said he found the statistics “alarming.”

Don Gathers, a deacon at the First Baptist Church and founder of Charlottesville’s chapter of Black Lives Matter — said that stop and frisk is a racist policy: “[Stop and Frisk] is a very race-based, racist, failed policy,” he said. “[The police] get … returns from the instability that they create in the community.”

My first reaction (to borrow a line from the Instapundit blog): Why are municipalities run by progressives such cesspools of discrimination?

My second reaction: Maybe there is a problem, but I’m not going to believe it on the authority of the Cavalier Daily, the ACLU or Black Lives Matter. Here’s the obvious counter: If African-Americans in Charlottesville are nine times to be guilty of crimes as whites, then the stop-and-frisk disparity is not unreasonable.

However, the Cavalier Daily did present evidence suggesting that the disparity was real, though not as bad as a nine-to-one ratio would indicate.

In 2016, a more comprehensive report revealed that out of the 97 detentions, 74 of the cases involved black individuals, but only 15 — or about 17 percent — of the individuals were arrested or served summons. Comparatively, out of the 35 white people that were stopped in 2016, 11 — roughly 31 percent — of them were arrested or summoned to court.

In either case, a minority of those frisked were worthy of arrest. But blacks were only half as likely to be arrested or summoned — a big disparity, to be sure, but far short of a nine-to-one ratio. What we don’t know is if there are legitimate reasons for that smaller disparity. The assumption of racism is often unwarranted. Conversely, the fact that assumptions of racism are often unwarranted does not mean that they are always unwarranted. This may be such a case.

“Another important step is to dig deeper into the data,” said City Manager Maurice Jones. “We’ve got a group of folks who will be doing that with the City Manager’s Office, the police department, the City Attorney’s Office [and] the Commonwealth Attorney’s office as well and getting a better understanding of some of the issues associated with [the data].”

When stop-and-frisk was a hot controversy in New York City a few years back, I sympathized with the police and those who argued that eliminating the policy would make it more difficult to combat crime. I did not think it would end well when Mayor Bill DeBlasio ended the practice. As it turns out, the New York City crime rate has continued to decline. It’s not often that I find myself changing my mind about left-wing politicians, but in this instance DeBlasio proved correct. Stop-and-frisk was causing unnecessary resentment among minorities, and police have other crime-fighting tools that work as well or even better.

Bacon’s bottom line: Let’s see if Charlottesville’s police can provide a convincing defense of the racial disparity in stop-frisks. If they can’t, the practice should end, and the police should devise other tactics for fighting crime.