There’s loads of interesting data in Virginia Commonwealth University’s new report on the university’s impact on Virginia and the Richmond region. I see no need to summarize the report’s main conclusions — I refer you to the executive summary posted here, re-published on this blog in partnership with the VCU Center for Urban and Regional Analysis. Rather, I dove into the report this morning to see what I might discover, and I surfaced with several pearls of data.

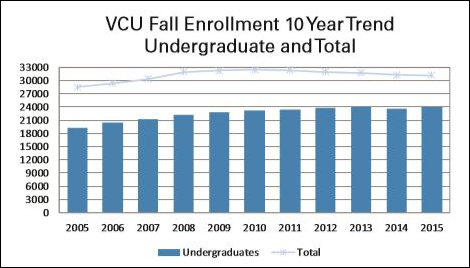

Overall enrollment trends. After experiencing a growth spurt through 2009, hitting a high of 32,434 students, enrollment at VCU has declined modestly since then, by 1,192. Beneath the seemingly placid surface of small year-to-year changes, there has been tremendous churn. Undergraduate enrollment has continued to surge, increasing 25% over the 10-year period shown above. But graduate enrollment has declined by 33%.

The report gives no explanation for the drastic fall-off in graduate programs. Were budgets cut? Did the programs lose competitiveness compared to other institutions? Did graduate enrollments tumble nationally, or was this a VCU phenomenon?

The report gives no explanation for the drastic fall-off in graduate programs. Were budgets cut? Did the programs lose competitiveness compared to other institutions? Did graduate enrollments tumble nationally, or was this a VCU phenomenon?

Judging by a separate table showing the number of degrees granted, the fall-off seems to be concentrated in the schools of Education and Humanities & Sciences. Graduate degrees granted by the School of Business increased, while most other remained stable. The root of the phenomenon is probably specific to Education and Humanities.

Should it be a source of concern to see VCU losing ground in the production of post-graduate degrees? Not necessarily. When it comes to creating economic value, not all degrees are created equal. Graduate business, medical or engineering degrees, in which VCU held its own, are arguably in greater demand in the workforce than, say, psychology, history or English degrees. On the other hand, I’m not aware of any diminution in demand for teachers, so the reason for the decline in education M.A. is not immediately apparent. Whatever the case may be, that’s an economic analysis I would love to read.

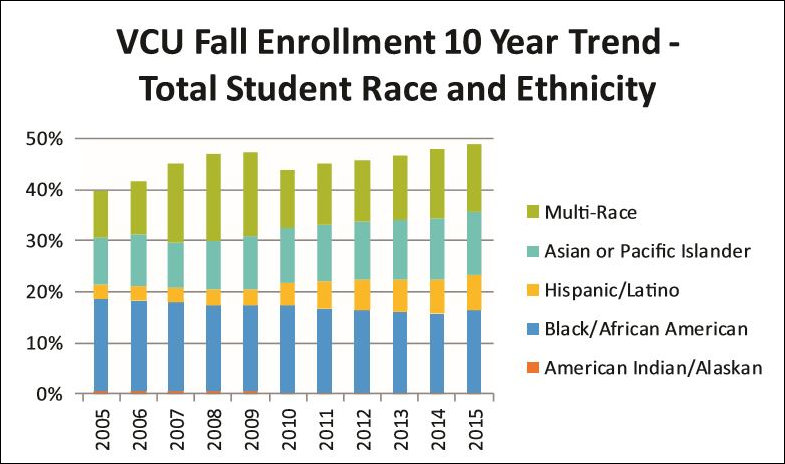

Minority enrollment. The number of minority enrollments are up over the 10-year period. The main gains have come from Hispanics, Asians and students identifying as multi-race. However, African-American enrollment has declined, and the American Indian/Alaskan student population in 2015 has become so negligible that it cannot be perceived by the naked eye on VCU’s chart.

Two notes of interest: First, I am astonished by the large percentage — well over 10% — of the students classifying themselves as multi-racial. That number is large and growing, probably reflecting the increased percentage of interracial marriages and births (as opposed to, say, an increased emphasis on recruiting multi-racial students). The idea of the American melting pot, often disparaged, seems to be alive and well — at least at VCU.

Second, the decline in African-American enrollments is potentially concerning, especially given VCU’s self-declared role as an “institution of opportunity” serving first-generation college students. If this dip reflects an opening up of opportunities for black students elsewhere, this may be a positive thing. If it reflects a declining pool of college-ready black students graduating from Virginia high schools, or a perception that college is unaffordable, it is alarming. Perhaps there is another explanation entirely. Finding answers to such questions was not the purpose of the report, so the trend went un-examined. But it bears looking into.

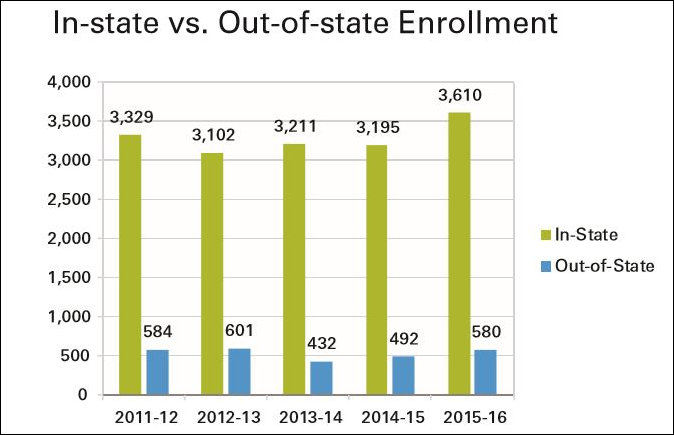

Out-of-state enrollment. Out-of-state enrollment, an indicator of a university’s recognition and prestige beyond state lines, remained constant over the five-year period covered, although it did experience a terrifying drop in 2013-14 before recovering the next two years.

Out-of-state students are coveted because public Virginia universities charge them significantly more than that it costs to educate them. Speaking generically of Virginia public colleges, out-of-state students help subsidize the tuition of in-state students. Low enrollment of out-of-state students helps explain why VCU charges the fourth-highest tuition of any public university in the state.

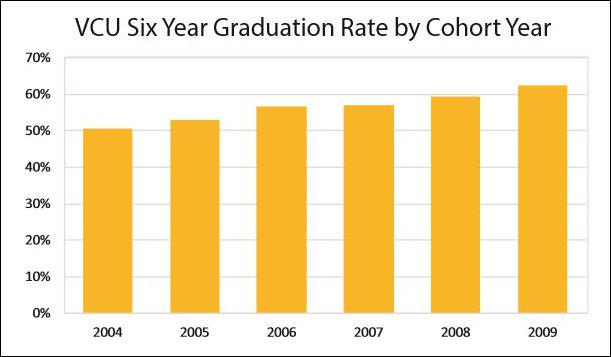

Graduation rate. Let’s close with some good news. VCU has taken to heart the injunction to improve student retention. The six-year graduation rate has improved from 51% for the class of 2004-2005 to 61% for the class of 2009-2010, moving VCU closer to the 70% rate for all Virginia institutions. VCU’s performance compares favorably to peer institutions (with comparable demographics), which have seen slow to flat growth in their graduation rates.

Higher graduation rates means fewer ruined lives. When students, especially poor students, fail to complete college, they don’t achieve the workforce credential — a diploma– needed to obtain a stable, higher-paying job. It is exceedingly difficult for drop-outs to pay off student debt that averages $32,000 at VCU. Judging by this graph, VCU seems to be taking very seriously its obligation to boost graduation rates.