A LinkedIn office building in Sunnyvale, Calif. — insulated from the street by a parking lot and landscaping berm — hews to traditional “sprawl” design. The rest of the campus does better but still misses an opportunity to connect with the surrounding community.

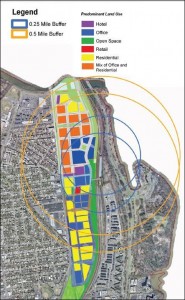

Sunnyvale, Calif., wants to reinvent a 60’s-era industrial office park as an innovation district. It’s making progress but suburban sprawl is not an easy habit to break.

by James A. Bacon

LinkedIn Corp. has built a wildly successful business model around connecting business people through cyberspace. Ironically, the fast-growing Silicon Valley corporation gives short shrift to connecting people in the physical world. Its new corporate campus in Sunnyvale, Calif., located in an emerging “innovation district,” misses an opportunity to foster creativity by encouraging employees to interact with others outside the organization.

In some ways, the LinkedIn campus represents an improvement on the traditional sprawling settlement pattern of Silicon Valley. The facility is higher density than neighboring office and industrial buildings in Peery Park, one of the valley’s oldest office parks. The company conserves acreage by replacing open parking lots with a five-level deck. The buildings have interesting architectural features and the landscaping is attractive.

Erik Calloway

But the LinkedIn complex falls short of what it could have been, Erik Calloway told me when I visited the San Francisco Bay area this spring. An urban designer with Freedman Tung & Sasaki, the firm engaged to help the City of Sunnyvale develop Peery Park as an innovation district, Calloway had ridden his motorcycle from San Francisco to show me how urban design can stimulate — or dampen — economic innovation. If only LinkedIn had tweaked the layout, he says, it could have opened the campus to the outside world, contributing to the vitality of the district and perhaps to its own enterprise. Says Calloway: “They weren’t focused on connections to the district.”

For much of American history, major corporations located major facilities in downtown business districts in order to avail themselves of the wealth of professional services, particularly bankers and lawyers, located nearby. Then in the post-World War II era, many corporations fled decaying cities to the suburbs, setting up self-contained campuses or office parks that were seen as serene, tranquil, far from the madding crowd. Now the movement is reversing, as corporations seek to gain competitive advantage by building innovation ecosystems in which they engage in intense interaction with collaborators outside the organization.

Many cities are evolving “innovation districts,” a concept popularized earlier this year by Bruce Katz and Julie Wagner with the Brookings Institution. Innovation districts, they write in “The Rise of Innovation Districts: A New Geography of Innovation in America,” are where “leading-edge anchor institutions and companies cluster and connect with start-ups, business incubators and accelerators.” Typically, these areas are physically compact, walkable, bikeable and transit-accessible, and sport a rich variety of amenities from restaurants to apartments.

Innovation districts are found mainly in cities built in the pre-automobile era because those districts possess the attributes — research universities, walkable streets, higher densities, mixed uses and an inventory of affordable older buildings — required to stimulate enterprise formation. Sunnyvale is notable for its effort to carve an innovation district out of mid-20th century, autocentric suburbia. If the Sunnyvale experiment is successful, it could provide a new economic-development template for suburbia.

As someone who combines the academic viewpoint of Katz and Wagner with a hands-on practice of an urban planner actually working to create and implement an innovation district, Calloway provides a valuable perspective.

Cities are changing from the scattered, low-density pattern derisively known as “suburban sprawl” to more compact forms, he says. Unlike some critics he doesn’t castigate sprawl as a disaster. Citing research he has done for an upcoming book on the subject, he asserts that sprawl arose after World War II in response to social and economic forces such as mass production, the spread of automobile ownership and construction of freeways. Developing cheap land by applying assembly-line principles to urban planning provided affordable middle-class housing to millions of Americans. “It worked well at the time. It provided a lot of wealth and prosperity.”

Silicon Valley was developed along that model: low-density suburbs served by streets designed with automobility foremost in mind. But sprawl created problems, Calloway says. In Silicon Valley traffic congestion and pricey housing were accentuated by sharp growth limits and surging demand created by the extraordinary success of the region’s high-tech industry. Unlike nearby San Francisco, which evolved to greater densities over the decades, the Valley has not. With some of the highest real estate prices in the world, it has largely displaced the poor and working class.

On a more global level, the nature of work has changed as the economy has evolved from a hierarchical, assembly-line model to a digital economy. Selling more stuff cheaper is no longer the primary path to prosperity, Calloway argues. Access to raw materials, transportation and abundant labor are secondary considerations. Now the mantra is innovation. Take shoes, for example, a product that humans have been fabricating for centuries. The challenge for a company like Nike isn’t to keep costs down so it can sell shoes cheaper than anyone else — although cost is a consideration — it’s applying technology to create shoes that have features that shoes never had before, such as, perhaps, the ability of buyers to customize their shoes online.

The question, then, is how to organize companies and their employees to maximize creativity and innovation. Continue reading →

Here’s the first reason you’re in trouble — old people. Or, more precisely, retired government old people. Virginia can’t seem to catch up to its pension obligations. The state says the Virginia Retirement System is on schedule to be fully funded by 2018-2020. But the state’s defines 80% funded as “fully funded,” which leaves a lot of wiggle room. The VRS also assumes that it can generate 7%-per-year annual returns on its $66 billion portfolio. For each 1% it falls short of that assumption, state and local government must make up the difference with $660 million. As long as the Federal Reserve Board pursues a near-zero interest rate policy, depressing investment returns everywhere, that will be exceedingly difficult. A lot of very smart people think 5% or 6% returns are more realistic. In all probability, pension obligations will continue to be a long-term burden on localities.

Here’s the first reason you’re in trouble — old people. Or, more precisely, retired government old people. Virginia can’t seem to catch up to its pension obligations. The state says the Virginia Retirement System is on schedule to be fully funded by 2018-2020. But the state’s defines 80% funded as “fully funded,” which leaves a lot of wiggle room. The VRS also assumes that it can generate 7%-per-year annual returns on its $66 billion portfolio. For each 1% it falls short of that assumption, state and local government must make up the difference with $660 million. As long as the Federal Reserve Board pursues a near-zero interest rate policy, depressing investment returns everywhere, that will be exceedingly difficult. A lot of very smart people think 5% or 6% returns are more realistic. In all probability, pension obligations will continue to be a long-term burden on localities.