by James A. Bacon

Foes of the proposed Bi-County Parkway, which would skirt the Massassas battlefield, are more optimistic than ever that the highway mega-project will never be built. Del. Tim Hugo, R-Fairfax, and Sen. Richard Black, R-Loudoun, proclaimed at a press conference yesterday that the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) “is not actively working on the Bi-County Parkway” or the related agreement with the National Park Service, which would close Rt. 234 through the battlefield and install traffic-calming measures on Rt. 29.

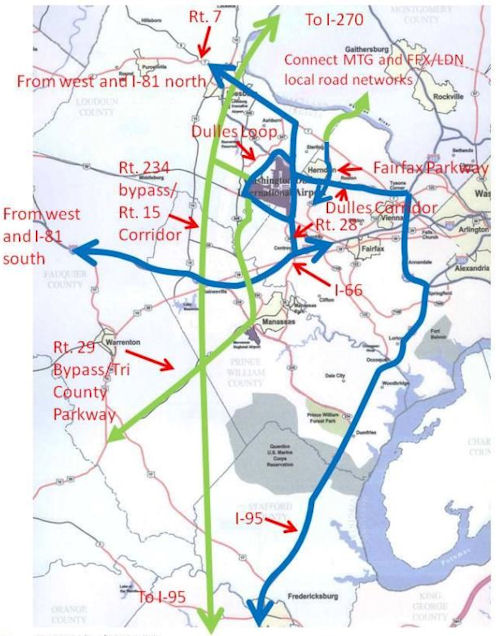

Said Hugo in a prepared statement: “For over two years, this has been a hard fought battle to stop an ill-conceived transportation project that would add thousands of cars onto I-66, worsening traffic congestion from Arlington to Fauquier. I am pleased that VDOT has shifted its focus to those transportation projects that will provide the most relief for Northern Virginia’s commuters and improve Virginia’s transportation infrastructure. ”

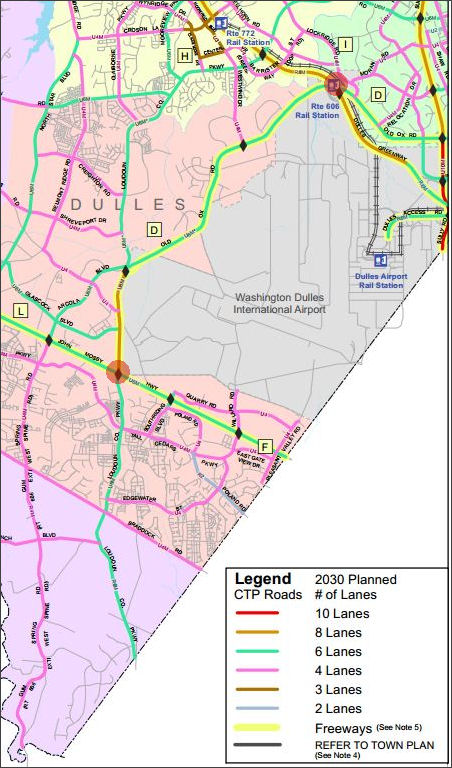

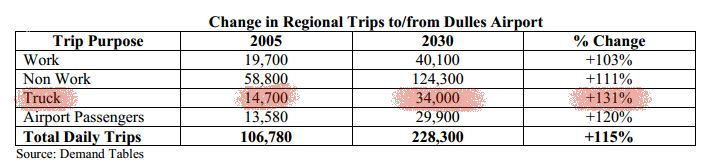

The proposed $400 million Bi-County Parkway will be subjected to a newly instituted Return on Investment analysis that ranks proposed transportation projects by benefits to the public such as congestion mitigated and economic development stimulated. The proposed four-lane highway, envisioned as part of a larger road complex providing superior transportation access for Washington Dulles International Airport, would do relatively little to alleviate current traffic congestion; indeed closing Rt. 234 would re-route more drivers onto an already-congested Interstate 66. The justification given for the road is to mitigate future congestion from growth that is projected to occur west and southwest of Dulles.

Transportation Secretary Aubrey Layne cautioned that that subjecting the Bi-County Parkway to the new rating process does not mean that it is dead. Rather, it has been put on hold. It would be foolish for the state to make any decisions until that process is complete, he told the Washington Post. “A lot of people are trying to prejudge where this is going to go.”

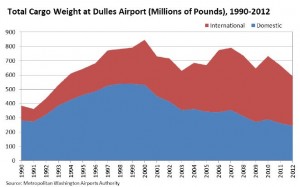

Bacon’s bottom line: It’s probably too early to celebrate. Hugo and Black are drawing attention to a new procedural obstacle that the project will have to surmount. The Parkway undoubtedly will rank lower than many other Northern Virginia transportation projects, such as proposed improvements to I-66, for congestion mitigation. If that were the sole criteria for funding, it would be Dead on Arrival. But the McDonnell administration also plugged the Parkway as a way to jump-start efforts to build the air cargo business at Dulles, which could result in hundreds of millions of dollars of commercial development in Loudoun and Prince Williams counties, and Governor Terry McAuliffe, who deems himself pro-economic development, might think similarly. If the new ranking system gives sufficient weight to the project’s potential economic development benefits, it still could have legs.

Update: Martin DeCaro does some solid reporting on this development for National Public Radio. He posts a copy of Virginia Commissioner of Highways Charlie Kilpatrick’s letter to Hugo. I don’t see how Hugo concluded that VDOT has “shifted its focus” from that letter.