A North Carolina riverkeeper inspects testing samples of coal ash taken from the Dan River. Photo credit: WRAL.

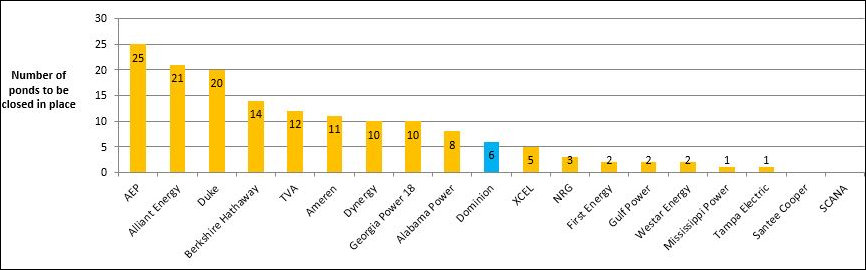

So, it looks like the there will be a pause in the solid-waste permitting process for Virginia coal ash. Governor Terry McAuliffe had submitted an amendment to legislation that, if approved, would require Dominion Virginia Power to compile more information on contamination around its coal ash sites and study alternative closure methods before the state issues the permits. Now Dominion has decided to go along, which means political opposition to the idea could evaporate.

“We concur that it is a prudent course of action to seek and consider an evaluation of the assessments on the appropriate closure methods based on the individual features of each site before seeking necessary solid-waste permits,” wrote Dominion CEO Thomas F. Farrell II. “Dominion finds the proposed amendments to Senate Bill 1398 to be workable, and is committed to completing the site assessments before pursuing solid waste permits regardless of the outcome of the legislation.”

McAuliffe’s amendment would restore key provisions to a bill co-sponsored by Sens. Scott A. Surovell-D-Fairfax, and Amanda F. Chase, R-Chesterfield, whose legislative districts include Dominion’s Possum Point Power Station and Chesterfield Power Station, each of which has millions of tons of coal ash to dispose of. (See the Richmond Times-Dispatch story here.)

Dominion had originally opposed the testing and study provisions, which were stripped out by the House of Delegates. But if the power company drops its opposition to McAuliffe’s amendment, as Farrell’s letter indicates, Surovell and Chase likely will get their way.

According to the bill summary, HB 1398 will require owners of coal ash ponds (1) to identify water pollution emanating from the ponds and address corrective measures, and (2) evaluate the feasibility of “clean closure.” Clean closure would entail removing the coal ash from ponds where it has been stored to lined landfills. Dominion has estimated that the cost of landfilling could amount to $3 billion, but environmental groups have argued that the cost would be much lower if the utility recycled the material as an additive to cement and other products.

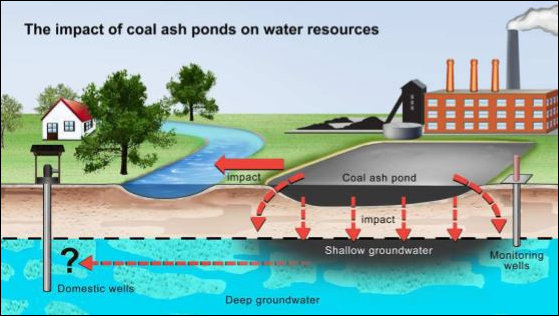

Bacon’s bottom line: Pausing the permitting process to get a better handle on what’s happening at the coal ash ponds is a good idea. Frankly, despite considerable testing by both Dominion, environmental groups and even Duke University, little can be said with certainty about the process at each of Dominion’s four sites by which groundwater migrates through the coal ash and contaminates either well water or nearby rivers and streams.

Any testing regime must be rigorous enough to provide definitive answers. The last thing we need is set of ambiguous results that Dominion and environmental groups try to spin to their advantage in another contest of P.R. and political clout. Any credible testing program should recruit outside experts, perhaps from Duke or perhaps from a Virginia university, who can identify the questions to be answered and what protocols will provide definitive answers.

Dominion has conducted tests on its property and found little evidence of contamination at Possum Point, Chesterfield and the Bremo Power Station, but a federal judge recently used Dominion data to conclude that coal ash its closed Chesapeake plant was contaminating groundwater. Testing by riverkeeper groups of groundwater and surface waters just outside of Dominion property show elevated levels of heavy metals which, at sufficient concentrations, can be toxic to aquatic life and human health. Additionally, Duke University has conducted extensive testing in North Carolina and Virginia using “forensic tracers” that have found elevated levels of heavy metals in groundwater near Bremo and Chesapeake. But other Duke tests have found that elevated levels of the carcinogen hexavalent chromium, also associated with coal ash, is endemic in piedmont groundwater and in many cases cannot be attributed to the coal combustion residue.

Complicating any analysis is the fact that trace levels of heavy metals and carcinogens are frequently found in groundwater and surface water as the result of natural processes. Levels vary depending upon local geology. The existence of trace elements of heavy metals in groundwater near coal ash ponds is not in itself proof that the heavy metals came from the coal ash. The trace elements could be ubiquitous in the area, but no one knows unless tests are conducted some distance from the power plants. Ideally, any testing regime for Dominion’s coal ash ponds should adjust for background levels of contaminants.

Another complication is ascertaining the movement of groundwater. For example, the water from several wells near Possum Point have shown elevated levels of heavy metals. It is easy to deduce from the proximity of the wells to coal ash ponds that the contaminants come from the ponds. But to demonstrate the point conclusively, one must show that the groundwater migrates from the coal ash ponds toward the wells, and not in some other direction. To make that proof, it is necessary to conduct extensive sampling and create detailed maps that mark the geographic scope and elevation (in feet above sea level) of the underground water and determine the direction of the water flow. Only if it can be documented that underground water is migrating from the coal ash pond toward the wells can one reasonably conclude that the coal ash is to blame for elevated levels of well-water contaminants. If the water is migrating away from the wells, the well-water contaminants probably have another source.

Adding another layer of complexity to the analysis is estimating how much contamination the groundwater picks up while migrating through coal ash. Dominion maintains that its coal ash pits do not come into contact with the water table; the deepest part of the ponds have a higher elevation than the underground water table. However, using Dominion’s own maps, the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) contends that the bottom reaches of the coal ash ponds at Bremo and Chesterfield intersect with the water table. If the SELC is right, groundwater that migrates through a portion of the coal ash could pick up contaminants along the way.

The question then arises, how long must the water be in contact with the coal ash in order to pick up trace metals? That is a function of the chemistry of the coal ash, how tightly or loosely the metals are bound to inert materials, and the speed of water migration, which depends upon the permeability of the clays and rocks. If the groundwater comes into contact with only a small percentage of the coal ash for a short time, the leeching of heavy metals could well be minimal.

If it can be demonstrated that measurable levels of metals leach into the groundwater, another question must be answered: What volume of contaminants, and how rapidly, does the groundwater feed into surrounding rivers and streams? While U.S. District Court Judge John A. Gibney Jr. found that Dominion’s Chesapeake Coal ash ponds did contaminate the groundwater and that the groundwater did reach the Elizabeth River in violation of the Clean Water Act, he also found no damages because the contaminants were so diluted by the massive water volume of the river that aquatic and human health were unaffected. Continue reading

by James A. Bacon

by James A. Bacon