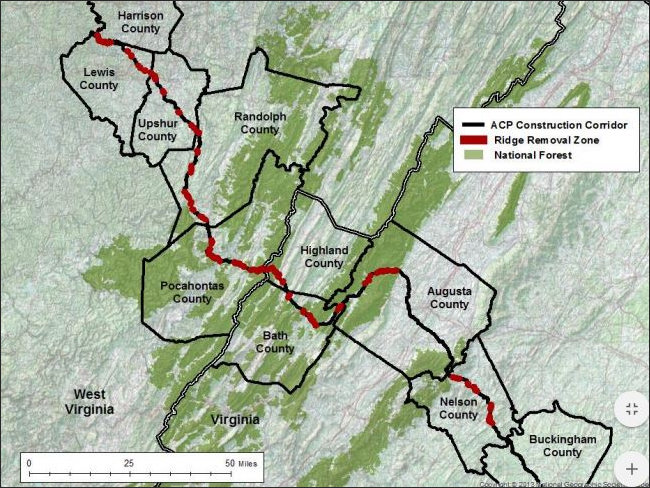

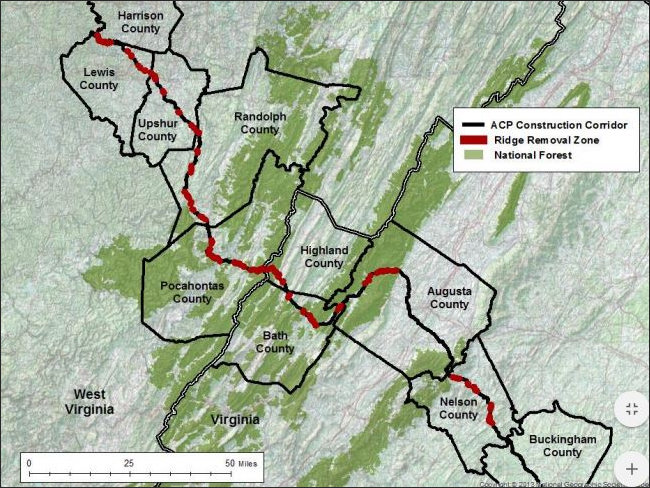

Ridge removal zones along the ACP route are shown in red based on Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition calculations.

From the perspective of its managing partner, Dominion Transmission, the Atlantic Coast Pipeline is looking more and more like a done deal. Dominion has completed more than 65% of the high-performance steel pipe needed to build the roughly 600-mile pipeline, and it has procured almost 85% of the land, materials and services it needs, pipeline executives disclosed today.

Pipeline officials also say they are nearing the end of a two-year regulatory process. In December, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) issued a favorable draft Environmental Impact Statement. The final EIS is expected by June 30th.

“We have every reason to believe the favorable draft EIS and — ultimately — the final EIS will provide a strong foundation for final approval of the project later this summer or in the early fall,” stated Diane Leopold, CEO of Dominion Energy, the pipeline’s managing partner, in a press conference this morning.

But foes of the pipeline have raised an issue they hope will derail ACP’s plans. The pipeline will cross 38 miles of mountains in Virginia and West Virginia that would require 10 feet or more of their ridge tops to be removed — up to 60 feet in places, they claim. Comparing the pipeline construction to the coal industry’s practice of mountaintop removal, Mike Tidwell, director of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network, said in a dueling press conference today that the pipeline would cause “irrevocable harm” to the region’s environment.

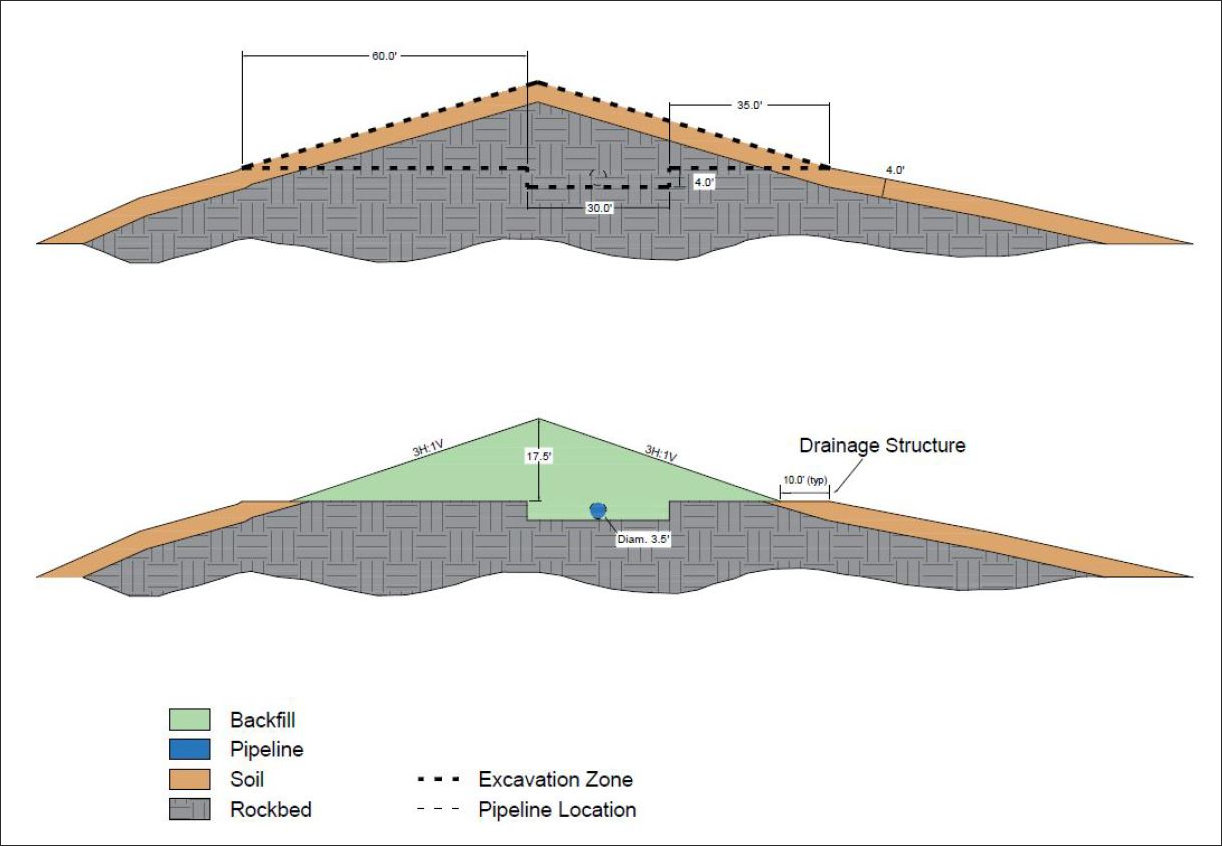

Creating flat space on steep mountaintops to provide room for trench digging and construction activity would require removal of an estimated 247,000 dump-truck loads of excess rock and soil, asserted Dan Shaffer, spatial analyst with the Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition. Finding somewhere to place the massive volume of this “overburden” even temporarily without causing runoff into rivers and streams will be a huge challenge, he said, And, even though ACP would be required to restore ridge lines to their “approximate original contour,” breaking up the rock causes the volume to swell, creating a large amount of spoil that must be permanently disposed somewhere.

Pipeline foes raised these concerns about “mountaintop removal” with FERC in comments submitted during the draft impact statement. The draft document “failed to address this important issue,” noted Ben Luckett, an attorney with the Appalachian Mountain Advocates. He contends that the pipeline requires a new draft EIS and a new public comment period.

Even if FERC declines to re-open the draft process, anti-pipeline forces plan to raise the issue in state “401 certification” water-quality reviews. In Virginia the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) has promised to allow extensive public input. Given the potential for massive runoff, erosion and sedimentation, said Luckett, “states cannot reasonably make a determination that the pipeline won’t lead to violations of clean water standards.”

Dominion spokesman Aaron Ruby strenuously objected to the comparison of pipeline construction with coal-mining mountaintop removal, which “conjures up images of mountains that have been completely flattened. … We’re not removing the tops of mountains. That is total misinformation.”

Building pipelines in rugged mountain terrain “is not new to us,” said Leslie Hartz, vice president-pipeline construction for Dominion Energy. Only “small clearings” will be required for construction purposes on ridge lines. Contractors will restore the terrain with native material to its original contours, as required by FERC. There may be a “small amount” of spoil left over, but ACP has identified ways to employ it usefully for other purposes.

In describing the construction process, Hartz said the project would be broken into 17 “spreads,” or construction units, each of which will be built simultaneously in linear fashion. Mountainous terrain would have shorter lengths, perhaps 15 to 20 miles. Some blasting would be required to remove rock, she said. Material left over after the mountain contours are restored will be used to re-establish habitats and create protective barriers to restrict access to right of way.

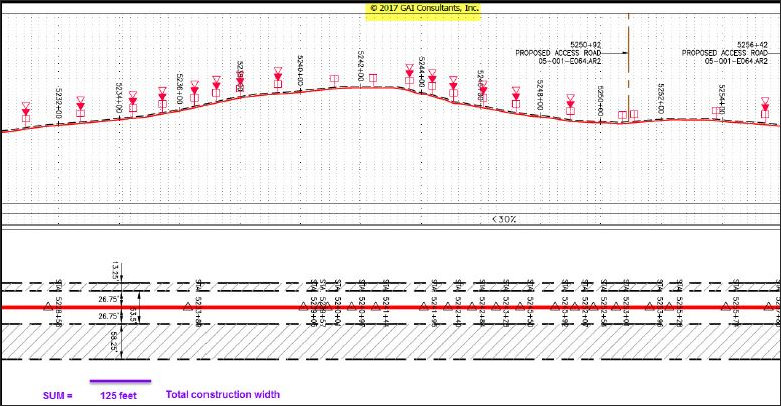

Pipeline foes question whether ACP fully comprehends the challenges it faces. The Friends of Nelson, contracted with Blackburn Consulting Services LLC to walk the route along Roberts Mountain. The soil there is thin, and construction will require extensive blasting to remove enough bedrock to dig pipeline trenches eight feet deep. Some slopes along the route are precipitous, as much as 65°. (Forty degrees qualifies for a black diamond ski slope.) Creating 125-foot wide rights of way would require removing enormous amounts of rock.

States an issue brief released by the pipeline opponents:

Numerous engineers who have looked at this issue have asked the obvious question: What does Dominion plan to do with the tremendous amount of overburden? Dump it into surrounding valleys as companies do with mountaintop removal for coal? Truck it off the mountains with massive dump trucks? And take the massive amounts of rock and soil to what location?

While ACP has vowed to restore the mountains to their approximate original contour in line with FERC requirements, foes say there is a qualifier. ACP will restore the mountain ridges to the extent practicable “taking into consideration cost, existing technology, and logistics in light of the overall purpose of the ACP.”

Ruby retorted that ACP understands the challenges far better than the pipeline foes. For starters, he said, there is no need to flatten a 125-foot-wide area on the ridge line, he said. The company will carve out just enough space to excavate the trench, which will be “significantly narrower” than 125 feet.

Further, he said, the company has “one of the most protective programs ever used by the industry, specifically designed to provide enhanced protection of soil erosion. We have site-specific plans for every steep slope we encounter, based on the unique conditions and characteristics of each slope.” These plans take into account the soil type and depth, the grade of the slope, the depth of the bedrock, the width of the ridge line and the types of vegetative cover.

ACP also disputed the Dominion Pipeline Monitoring Coalition estimate of construction impact.

In explaining how he calculated miles of ridge-line impacted and thickness of overburden to be removed, Shaffer said that he was forced to rely upon publicly available information. He used the centerline depicted on Dominion Project Facility Maps submitted to FERC (here & here), generated a 125-foot Right of Way from that and overlaid them with topographical and elevation data. He estimated the thickness of the mountain that would be removed by creating transects across the Right of Way at periodic intervals and sampled the elevation value along each transect. The methods, he conceded, were “fairly simple.” While acknowledging some room for error, Shaffer said there was no escaping the conclusion that the impact would be significant.

The assumption that ACP will cut away a full 125 feet is wrong, Ruby said. Without the assumption, the rest of the analysis falls apart.

There must be a better way for federal agencies to review infrastructure mega-projects.

There must be a better way for federal agencies to review infrastructure mega-projects.

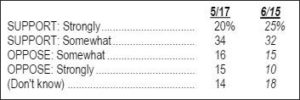

A month ago, the Chesapeake Climate Action Network (CCAN) published the results of

A month ago, the Chesapeake Climate Action Network (CCAN) published the results of