by Reed Fawell III

“Going to Yale Could Make You Rich, or Lonely,” by Lyman Stone, published in The Federalist on Dec. 19, 2018, exposed some surprising findings regarding the costs and benefits of college attendance. Stone is worth quoting at length:

There’s a long-standing economic consensus that, for high schoolers smart enough to get admitted into the University of Kentucky (average SAT score of about 1000-1100) and Yale (average SAT score of about 1400-1600), it really doesn’t matter which college they attend … [Researchers have identified] how much money students earn 10 or 20 years later. It turns out going to Yale doesn’t add one penny to how much money a Yale admit earns.”

At least, that’s what economists used to think. But that research was based on a sample that basically dropped all part-time workers and excluded almost all women for various reasons. Brand-new economic research released just last week, however, overturns this long consensus. Economists have now found … that, for a male student admitted at a highly selective school like Yale, it doesn’t matter where he goes. If he goes to Yale, he’ll do fine surrounded by brilliant peers. If he goes to the University of Kentucky, he’ll do fine as a big fish on campus.

But for women, attending a highly selective school has massive effects. A young woman admitted to both UK and Yale faces a resounding choice about her future life. If she chooses Yale, odds are that her annual income when she is 40 will be about 40-70 percent more. However, her odds of ever getting married are about 25 percentage points, or about one third, lower. Crucially, her odds of having a higher income rise only if she gets married! So really, there are three outcomes:

- Outcome one: our hypothetical female student goes to UK, gets a degree, has about a 75% chance of being married by age 40, and probably makes about $50,000 a year.

- Outcome two: our hypothetical student goes to Yale, gets a degree, is still unmarried at age 40, and still only makes about $50,000 a year. If she goes to Yale, she has about 50% odds of this outcome.

- Outcome three: our hypothetical student goes to Yale, gets a degree, gets married, and ends up making about $100,000 a year. There’s about 50% odds of this outcome.

In other words, Yale does not make women better off: It makes women who win the meritocracy tournament better off, and leaves the rest no better off, but with plenty of debt and no spouse. Crucially, the study authors can’t say why this is happening, but a substantial driver seems to be about spousal characteristics. Going to Yale seems to make women marry much higher-earning men than going to UK does, even for women of similar backgrounds and SAT scores. Either Yale women find these men, get married, and end up as a wealthy power couple, or they hold out for the perfect guy … forever.

… Nobody tells young women this when they are 18. Nobody lays it out for them what kind of choices they’re facing, and what the odds actually are. … Those odds won’t look so great to a lot of women who get into highly selective schools.

The basic finding that it does not matter where you go to college if you are a highly qualified student was first published 16 years ago. As explained this past Dec. 11 by Derek Thompson, staff writer at Atlantic, in “Does It Matter Where You Go to College?”

“In November 2002, the Quarterly Journal of Economics published a landmark paper by the economists Stacy Dale and Alan Krueger that reached a startling conclusion. For most students, the salary boost from going to a super-selective school is “generally indistinguishable from zero” after adjusting for student characteristics, such as test scores … Dale and Krueger even found that the average SAT scores of all the schools a student applies to is a more powerful predictor of success than the school that student actually attends.

These findings raise collateral issues, such as impacts on minorities and the opting out of the trained profession by women in elite universities, some of them yet resolved, but all important and worthy of attention. For example, again quoting for the same Atlantic Magazine article:

This month, economists from Virginia Tech, Tulane, and the University of Virginia published a new study that reexamines the data in the Dale-Krueger study. Among men, the new study found no relationship between college selectivity and long-term earnings. But for women, “attending a school with a 100-point higher average SAT score” … (can) have is a huge effect. Has one of the most famous papers in education economics been debunked? Not quite, says Amalia Miller, a co-author and an economist at the University of Virginia. “The difference we found is that college selectivity does seem to matter, especially for married women … For the vast majority of women, the benefit of going to an elite college isn’t higher per-hour wages. It’s more hours of work. Women who graduate from elite schools delay marriage, delay having kids, and stay in the workforce longer than similar women who graduate from less-selective schools.

A few obvious questions arise from these findings.

- Should we rethink how college rankings impact an applicant’s post-education outcomes?

- Might college rankings imply a benefit to students where there is none and omit other significant impacts students should know before selecting a college?

- Is the great variation between schools’ tuition justified?

- How can we ensure that these findings, known to the educational establishment since the 2002, are known to students (and their parents) when they apply to colleges?

- Do these findings justify substantial changes in the entire college application process?

The findings also touch upon broader economic and social issues such as soaring college costs, ballooning student debt, falling marriage and birth rates, campus unrest, and increasing polarization of the citizenry.

Might these demographic trends be driven, in part, by the growing divide between students who attend elite universities and every one else, whether they go to college or not? Is it good social and economic policy to perpetuate this divide? Is it good education policy?

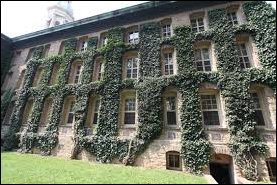

Indeed, should we reconsider the role that the elite higher ed institutions — not just the Harvard, Yale, and the other Ivies but public elites such as the University of Virginia and the College of William and Mary — play in our society?

As stated by Professor Patrick J. Deneen, in “The Ignoble Lie, How the New Aristocracy Masks its Privilege, in the April 2018 edition of First Things Magazine:

Our ruling class is more blinkered than that of the ancien régime. Unlike the aristocrats of old, they insist that there are only egalitarians at their exclusive institutions. They loudly proclaim their virtue and redouble their commitment to diversity and inclusion. They cast bigoted rednecks as the great impediment to perfect equality — not the elite institutions from which they benefit. The institutions responsible for winnowing the social and economic winners from the losers are largely immune from questioning, and busy themselves with extensive public displays of their unceasing commitment to equality. Meritocratic ideology disguises the ruling class’s own role in perpetuating inequality from itself, and even fosters a broader social ecology in which those who are not among the ruling class suffer an array of social and economic pathologies that are increasingly the defining feature of America’s underclass. Facing up to reality would require hard questions about the agenda underlying commitments to “diversity and inclusion.” Our stated commitment to “critical thinking” demands no less, but such questions are likely to be put down—at times violently—on contemporary campuses. …

This helps explain the strange and often hysterical insistence upon equality emanating from our nation’s most elite and exclusive institutions. The most absurd recent instance was Harvard University’s official effort to eliminate social clubs due to their role in “enacting forms of privilege and exclusion at odds with our deepest values,” in the words of its president. Harvard’s opposition to exclusion sits comfortably with its admissions rate of 5 percent (2,056 out of 40,000 applicants in 2017). The denial of privilege and exclusion seems to increase in proportion to an institution’s exclusivity.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.