If all you want is a doctor who will prescribe you pills, Dr. Neal Carl is not the man for you. If you want to understand the metabolic pathways of your medication, he’ll take the time to explain.

Personalized medicine is the new frontier of healthcare. DNA testing has become so inexpensive that it is now practical to develop wellness regimes tailored to peoples’ individual genomes. Virginia’s biggest endeavor in this field is taking place in Northern Virginia under the auspices of Inova Health System’s Center for Personalized Health. But another approach to health care delivery is taking place here in Richmond. My friend Linda Nash has launched a next-generation concierge medicine business, WellcomeMD, whose physicians treat their patients based on an in-depth analysis of their DNA, gut biome, and a full-battery blood test.

To get a feel for how personalized medicine works, I took up Linda on an offer to have my DNA tested and then meet with WellcomeMD’s Dr. Neal Carl for a consultation. Except in rare instances, genes are not medical destiny. But they do influence our health in many ways, and knowing our genetic proclivities is helpful in crafting an approach to fitness and nutrition.

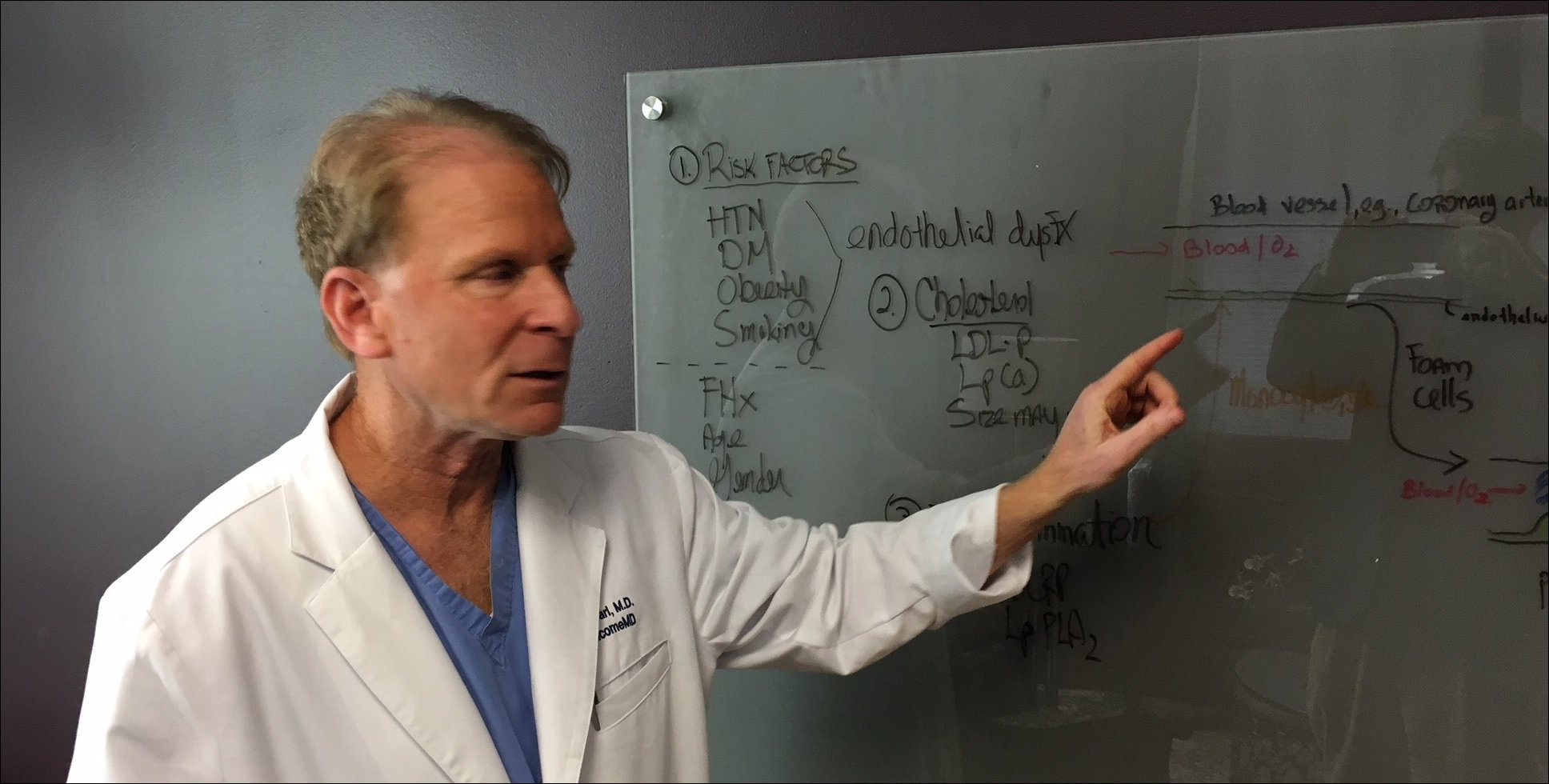

The testing process is absurdly easy. Visit the WellcomeMD office, take a cheek swab, send it off, and wait ten days for the results. Interpreting the findings, however, requires a background in genetics, proteomics, and metabolic pathways — subjects that few primary care physicians studied closely in medical school. But Carl has immersed himself in these disciplines and how they relate to wellness. After poring through the data on some 20 to 30 “actionable” genes — that is, genes that provide information that can inform us about individual fitness and nutrition — he sat down with me to go through the findings.

I never made it past Introductory Biology in college, so a lot of it was over my head. But here’s what I gleaned from the consultation: Like most people, my genes confer both strengths and weaknesses in the 21st-century struggle for health and wellness.

My genetic profile indicated that my power/endurance response is weighted in favor of endurance. I was never destined to develop a weight-lifter’s physique. I wasn’t genetically predisposed to become the fabled 90-pound weakling, but I was never going to become a Charles Atlas either. Lifting weights could increase my strength, but I’d never develop bulky muscles. Conversely, my body is genetically suited to moving oxygen to body tissues and metabolizing it efficiently. Practically speaking, I’m far better suited to fitness regimes that emphasize endurance over strength.

The genetic test also measures for the body’s ability to detoxify muscles after exertion. I fall in the middle range, suggesting that I needed a day’s break between intense workouts. I also have a proclivity for injury of tendons and ligaments, with special concern for the Achilles tendon.

All this rang true. While I was never a great athlete, I devoted 14 years of my life to serious study of Tae Kwon Do, the Korean martial art. On the side, I ran, lifted weights, and did aerobics. I was never the strongest, certainly not the fastest (Carl confirmed that I lack the fast-twitch genes), nor the most flexible, but I did have the capacity to finish grueling hour-and-a-half workouts while others were hugging the floor. If I could survive the first 45 minutes of a fight, I could definitely kick the other guy’s ass!

Without the benefit of medical coaching, I have fallen into a fitness regime consistent with what my body was telling me. These days, I sporadically lift light weights and do one or two bouts a week of intense half-hour cardio. My efforts at consistency are bedeviled on and off by minor problems with rotator cuffs, pulled muscles and once, in an ill-fated fling with barefoot running, a pulled tendon in my foot that left me limping for weeks. All of these traits were consistent with my genetic profile.

As for nutrition, my genes don’t put me at risk for obesity, but just gaining 10 to 12 pounds over my ideal weight does put me at risk for pre-diabetes. I have a metabolism that makes me gain weight more readily by consuming carbs than fat. I’m salt sensitive (which may help explain my hypertension), and I have a heightened cancer risk from eating charred meat — which is a major bummer, because half the meals I eat consist of grilled beef or chicken. This information is useful because, evidently, I have not naturally gravitated in life to a nutritional regime consistent with my genetic endowment. Things must change. There will be more broccoli and brussel sprouts in my future.

The body is an incredibly complex organism, and a handful of genes don’t tell the whole story. To get a full, rounded picture of my health, Carl also would test my gut biome. Intestines are a “second brain” loaded with neurotransmitters, he says. When your intestinal bacteria aren’t happy, you aren’t happy. If I were a patient, he also would get an in-depth blood panel looking at dozens of markers — far more than the normal primary care physicians would track. And he would integrate all that data into a holistic understanding of my health that encompasses exercise, nutrition, stress and sleep.

New medical model. Managing a patient’s wellness at this level of understanding is time-consuming, and primary care physicians, who typically have a roster of 3,000 patients, cannot do it. The business model of WellcomeMD calls for Carl to oversee only 300 patients.

Nash founded PartnerMD, a successful concierge medicine practice, before leaving the company selling out her interest several years ago. As soon as her non-compete clause expired, she was ready to roll out what she calls “concierge 2.0.” The old model allows doctors to spend more time with patients and give them more holistic care. But WellcomeMD pushes the envelope of medical practice.

“Genetics testing has to be part of concierge medicine going forward,” says Nash. “It really is a different model. For people who want to delve deeper into their genetics, their stress, their sleep, we’ll have more time and more advanced tools. Under the traditional model of medicine, there is no possible way to do this.”

Carl, who practiced general medicine at Chippenham Hospital, found the traditional medical model frustrating and unsatisfying. He saw on average about 25 to 30 patients a day, whom he had to move through in an assembly-line process. He focused on getting their “numbers” to look good — numbers for blood pressure, cholesterol, blood sugar, and the like.

“As it played out, a percentage of the patients didn’t feel that well. Many were on several. Even with good numbers, they still had bad events,” he says. By way of comparison, he notes that television broadcaster Tim Russert had a “normal” cholesterol panel, but he had an underlying cardiovascular disease that his doctors didn’t catch until he had a fatal heart attack.

“We were putting Band-Aids on things and not getting root causes,” Carl says of his former practice. “There had to be a better way to practice medicine.”

Many medicines have side effects, which require additional medication to treat the side effect. Now he combines personalized data with vitamin supplements and a holistic approach addressing what patients eat, how they sleep, and how they exercise to wean them from medication. Instead of treating pharmaceuticals as a magic bullet, the first option, he sees them as the alternative of last resort. He has succeeded in getting “dozens” of patients down from six or seven medications down to one or two, he says.

Carl concedes that he is “ahead of the science” in some areas. Based upon a theoretical understanding of metabolic pathways, vitamins like B6 and B12 should help patients deal with certain types of depression. But who has the incentive to conduct multimillion-dollar clinical trials to prove the efficacy of inexpensive vitamins? No one. On the other hand, the risk and cost associated with trying vitamins are very low. So, why not explore that option in treating patients?

Ideally, dispensing medicine should be more sophisticated than saying, “Your numbers don’t look good, here’s some medicine.” By limiting his practice to 300 patients, he has the time to measure, test, and measure again, before and after prescribing a medication. He also has the time to act as coach and educator to get patients more engaged with managing their health.

“It’s much harder to practice this way,” says Carl. “But I enjoy it.”

Wave of the future? It is common wisdom that the U.S. healthcare system spends far too much money on treatment and not enough on prevention. It is less commonly observed that much of the money spent on prevention — such as cancer screenings — is wasted as well. Human beings are so variable that preventive medicine that makes sense for one doesn’t necessarily make sense for another. Clearly, personalized medicine has the potential to achieve great savings and spur better outcomes.

But concierge-style personalized medicine is expensive. Wellcome MD charges a $2,500 annual fee over and above the cost of medical insurance and co-pays. Although personalized medicine provides them an option they didn’t have before, Americans with modest incomes may not be able to afford that extra fee. Moreover, the United States suffers from physician shortages. Medicaid patients find it difficult to find a doctor as it is. If enough physicians reduce their caseload from 3,000 patients to 300, this medical model could precipitate a social crisis.

But Nash is confident that WellcomeMD will be a net positive for the world. Personalized medicine is the wave of the future, she says. Too much medicine is reactive medicine, fixing the body after it’s broken. Personalized medicine is proactive medicine, helping motivated people manage their wellness and, ideally, reducing demand for the costly chronic medical conditions that make U.S. health care so expensive. The up-front cost may be more expensive. But that’s the way it always has been with new technology from laptops to smart phones. Affluent customers support the pioneers. Over time, as the early practitioners learn more and share their knowledge, costs come down and everybody wins.

Plus, there are benefits that can’t be measured with dollars and cents. “We want to help people live longer, more productive lives and live better,” Nash says. “My husband and I want to be hiking inn-to-inn in the Alps in our 80s, and we want to use every tool available to achieve that goal.”