by James A. Bacon

After spending a year and a half cleaning up the mess left by the previous administration — the Charlottesville Bypass, Norfolk’s Midtown-Downtown Tunnel, the U.S. 460 Connector in Tidewater — Transportation Secretary Aubrey Layne now has the opportunity to show whether or not he has the chops to handle a complex, politically charged transportation mega-project — the $2.1 billion in proposed improvements to Interstate 66 west of the Capital Beltway.

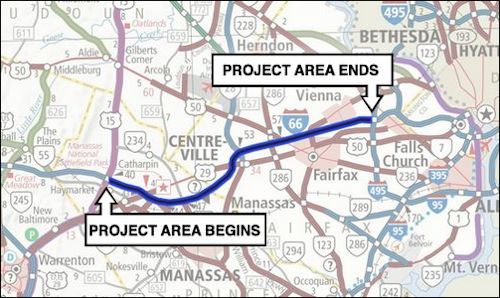

The Virginia Department of Transportation is focusing on two key dimensions to the mega-project, which is intended to address one of the most congested traffic corridors in Northern Virginia. The first is engineering. VDOT engineers have conceptualized a plan to build a corridor that will include three free lanes running both directions, two express lanes in each direction and high-frequency bus service linking commuters with major activity centers. That plan will be subject to extensive environmental review and public input.

The second key question is how the state will finance and manage the project. Should VDOT use the controversial public-private partnership (P3) legal/financial structure to build and operate the project, much as it did with the Interstate 495 and Interstate 95 Express Lanes projects? Should VDOT undertake the project entirely on its own? Or should it create a hybrid approach? The question assumes tremendous urgency given the problems created by the P3 approach with the Norfolk-Portsmouth tunnels and the U.S.460 Connector.

Parenthetically, I would add that there is a critical third dimension to the project which appears to be getting less attention: What will be the impact of the project on Northern Virginia land use patterns? Will the project subsidize suburban sprawl (scattered, disconnected, low-density land use patterns) in the far western reaches of the Washington metropolitan area, which in turn will generate more demand — and more congestion — in the years ahead? In other words, will the state spend more than $2 billion to “fix” a problem that will re-emerge a decade or two after the project is completed?

In an interview yesterday, I sat down with Layne to discuss the financial dimension of the project. The transportation secretary has given enormous thought on how best to structure highway mega-projects, balancing the twin imperatives of controlling costs and limiting risk.

Layne sees transportation projects as forming a continuum between a model in which VDOT does everything, and a privatization model in which all functions are delegated to a private-sector concessionaire through an asset sale or a long-term lease. Any project is comprised of several parts:

Design

Construction

Financing

Operation

Maintenance

Any one of these pieces can be performed by the state or out-sourced to the private sector. In Layne’s view, because no two projects are identical, there is no standard configuration. He tends to think that the private sector does a better job of designing and managing construction than VDOT, but not by such a wide margin that jobs should automatically default to private players. In other areas, VDOT has a clear advantage. The fact that VDOT can tap tax-free bonds, which sell at lower interest rates, and requires no private equity financing often means that the state can finance a project at less expense than a private entity.

But there is more to managing a project than driving for the lowest cost or, as the previous administration tended to do, the lowest up-front public subsidy. Costs should be viewed over the lifetime of the project, which runs 50 years or longer, after adjusted for risk. One risk is the potential for cost overruns. In the past, VDOT used to eat construction cost overruns, which meant that the taxpayer paid. But that risk, says Layne, usually should be transferred to the private contractor. Another risk is that toll revenues might not materialize as forecast. Private entities pay especially close attention to that risk, and they try to negotiate all manner of protections into a P3 project to offset it.

Express lane projects get tricky because a private entity is motivated to maximize toll-paying traffic through its tolled lanes in order to maximize revenue, while the state’s goal is to maximize the throughput of riders, which means encouraging High Occupancy Vehicles and buses. In its negotiations over Interstate 95, the original plan called for Transurban to make a $250 million up-front investment to provide a robust mass-transit component. But as the negotiations proceeded, the mass-transit piece got whittled down drastically. If High Occupancy Vehicles exceed 24% of total traffic on I-495 (35% on I-95), the state is obligated to pay 70% of Transurban’s lost revenue. Meanwhile, the state pays for mass transit on I-95 out of its own funds — an expense that was not included in the announced project cost.

Layne’s Law is to start by first defining what the state wants in a project, and only ascertaining which mix of functions it should outsource to the private sector. “I’d love to have a private-sector partner,” Layne says, “but only if the risk transfer makes sense.” In the case of I-66, bargaining away a robust mass-transit capability to protect a private entity’s revenue stream probably would not make sense.

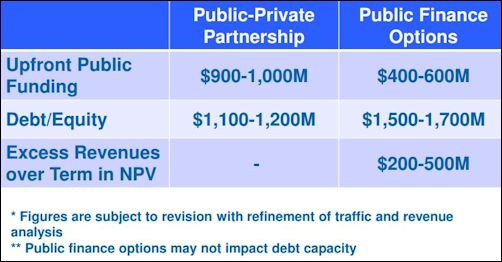

For the I-66 project, the state’s Office of Transportation Public Private Partnerships (OTP3) went through its usual procedure for determining a P3 structure for the project. Then the state hired public finance management consultants to determine, using the same inputs, how much it would cost the state to finance the project. Finally, Layne hired a third group to review the methodology and options proposed by the first two. This exercise showed that public financing with tax-free bonds and federal loan guarantees would not only be cheaper in the long run — saving $200 million to $500 million Net Present Value (NPV) over the lifetime of the project — but would require $400 million to $500 million less up-front public investment.

The state is scheduled to make a decision on how to structure the P3 deal in late summer. As it looks now, Layne says, “I-66 probably will be a P3 but not a concession [putting the private partner in total control of every step]. The private sector probably will build, design and operate it.”

Layne vows to keep “transparency and competition all the way through the deal.” If the state closes a P3 deal with a private party, the terms will be proprietary, says Layne, but he is obligated by law to personally certify that the terms are at least as good as if the state undertook the project itself. The new process laid out by P3 reforms law enacted by the General Assembly this year, he promises, will “stop another U.S. 460 from happening.”