by James A. Bacon

Both sides of America’s ideological divide acknowledge that student debt is a huge and growing problem, and both sides deem the climbing delinquency rate on student loans to be a bad thing. The question is what to do about it. The Obama administration has chosen to target private career colleges, whose students accumulate disproportionately large loans and fall behind on their debt payments at disproportionately high rates.

As the Obama administration points out, students at for-profit colleges represent only about 13 percent of the total higher education population, but about 31 percent of all student loans and nearly half of all loan defaults. “Higher education should open up doors of opportunity, but students in these low-performing programs often end up worse off than before they enrolled: saddled by debt and with few—if any—options for a career,” said U.S. Education Secretary Arne Duncan in a press release last year.

The recent publication by the Department of Education (DOE)’s online College Scorecard” was designed to bring some transparency to the cost and performance of public colleges, private not-for-profit colleges and private for-profit career colleges. There is no question that attendees of for-profit institutions experience are far more likely to fall short on student loan payments. But for-profit institutions argue that their programs aren’t the problem. The problem is that their students consist disproportionately of low-income and minority students who have trouble carrying their debt load regardless of the type of educational institution they attend.

Drawing upon College Scoreboard data, I decided to look and see what the situation looked like for Virginia-based institutions. Do private, for-profit colleges in the Old Dominion fit the stereotype of preying upon low-income and/or minority students and saddling them with unmanageable levels of debt?

First, I collected College Scoreboard data on (a) for-profit colleges, (b) community colleges, and (c) two public universities with high percentages of low-income and minority student bodies, Norfolk State University and Virginia State University. Then I plotted four different variables against the percentage of students at each institution that failed to pay at least $1 of the principal balance on their federal loans within three years of leaving school.

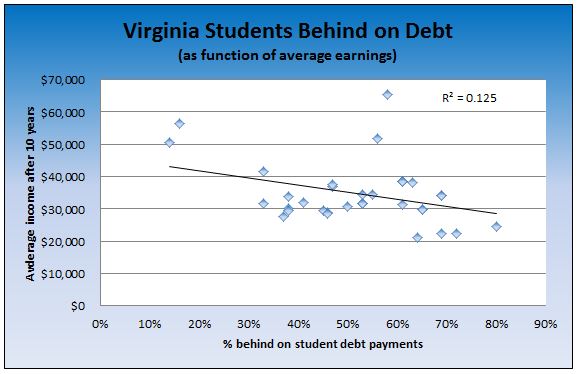

One logical explanation for the failure to pay down debt is low post-school earnings of students. The lower a student’s earnings, the heavier the burden of student-loan debt, whatever the size. There is indeed a modest correlation between earnings and debt troubles, as seen in this chart:

The R² of 0.125 suggests that about 1/8th of the variability in students’ ability to support their debt hinges on how much they earn after they leave college (making no distinction between whether they graduate or not). That’s not insignificant, but it’s less important than other variables.

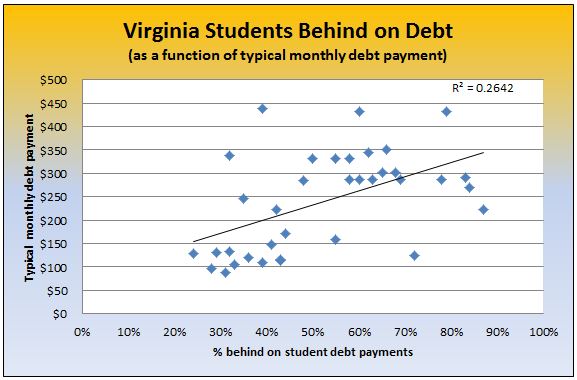

Next I looked at the size of the monthly student-loan payments. All other things being equal, students with larger monthly payments, I conjectured, would have a harder time keeping up with their debt than students with smaller payments. This hypothesis is borne out by the numbers.

The R² of 0.2642 was twice as high as that for post-college earnings, suggesting that this variable has twice the explanatory value as post-college earnings.

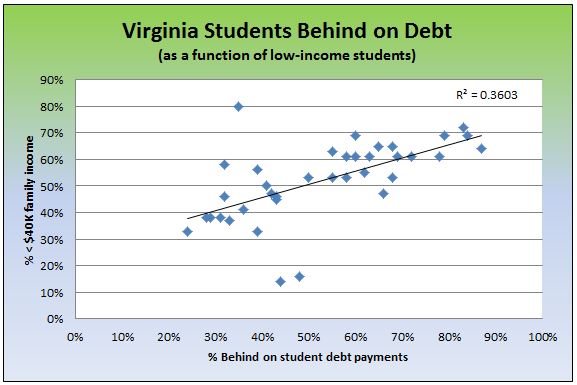

Next I plotted the correlation between debt troubles and the percentage of low-income students (family income less than $40,000 a year, the level at which students qualify for Pell grants) in an institution’s student body. This correlation was the tightest of the four variables examined.

The R² of 0.3603 suggests that more than 1/3 of the variability in student loan problems is associated with the income status of the student’s family. The two outliers at the bottom of the chart represent the Southside Regional Medical Center Professional Schools (in Petersburg) and the Chamberlain College of Nursing (in Arlington), both of which have fairly high percentages of low-income students yet very low percentages of students having trouble paying their loans. The outlier at the top of the chart is Centura College in Virginia Beach, which has a relatively low percentage of low-income students but high rates of loan troubles. That institution may deserve closer scrutiny.

Why would family income have anything to do with a student’s ability to pay debt? Family income is a major determinant of how much financial aid students get, including Pell grants and student loans, but the student is required to pay off the loans, not his or her family. Do poor families lack the resources to help students keep up debt payments when they’re having trouble? I suspect that is one possibility. Do students raised in poor families have different credit histories — are they raised with less financial literacy, with the consequence that they are more likely to make poor financial decisions? That, too, seems to be a reasonable possibility. Both conjectures would seem to be avenues worth exploring, but the College Scoreboard data cannot help us answer the questions.

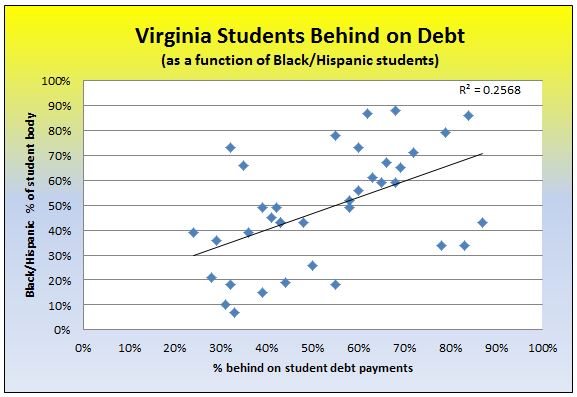

Finally, I looked at the correlation between debt troubles and race/ethnicity, in particular the disadvantaged minorities of blacks and Hispanics.

The R² of 0.2568 implies that about one quarter of the variability can be explained by race/ethnicity. In other words, all other things being equal, blacks and Hispanics are more likely to default than whites and Asians. I hesitate to draw any hard-and-fast conclusions from this correlation because I am not a competent statistician. The high default rate for disadvantaged minorities may be intertwined with their higher poverty rate, or it may be cultural — I just don’t know.

However, there are some conclusions that we can draw from the date. Private career colleges are far more likely than public colleges to serve low-income and minority student bodies. The higher propensity of their students to encounter difficulty repaying their student debt is largely, though not totally, explained by their backgrounds from minority, low-income families. But higher levels of debt resulting from higher tuition and lower post-school incomes also are factors.

Does that settle the debate? Hardly. Private career colleges can argue (1) they charge more than public institutions because they do not receive state funding, so it’s unfair to compare student debt loads; and (2) they do not filter their students by SAT scores, high school grades and other criteria. If the smartest, most academically prepared students gravitate toward four-year universities, private career schools cater to those who are less prepared academically. Insofar as academic aptitude is associated with success in pursuing occupations requiring cognitive skills taught in higher education, one would not expect attendees of career colleges to fare as well in the occupational marketplace as graduates of four-year colleges.

Thus, Obama administration is right to crack down on diploma mills that deliver little educational value. But it dodges the question of whether the federal government should be encouraging poor and minority students to attend colleges of whatever type in the hope of mastering skills for which they may not be academically prepared. Private career colleges provide a path of upward mobility for students who couldn’t attend traditional two- and four-year colleges. Should those who benefit from that opportunity be punished because others end up drowning in debt? Or should the DOE be more selective about who it lends money to, even if it means lending less to poor and minority students?

These questions are not easily answered. But we’ll never address the problem of excessive student indebtedness if we don’t ask them.