by James A. Bacon

The affordability crisis for American four-year colleges and universities is in part a problem of high tuition and fees, but it’s also a problem of low graduation rates, contends a new study by Third Way, a centrist think tank.

“A typical four-year public college graduates only 48.3% of first-time, full-time students within six years of enrollment,” states the report, “What Free Won’t Fix: Too Many Public Colleges Are Dropout Factories.” “That means first-time, full-time students that enter the average public institution are more likely to NOT graduate than they are to graduate from the school where they first enrolled.”

Among other key findings, based upon the Department of Education’s College Scorecard data:

- At the average four-year public college, nearly four in ten loan-holding students are unable to earn more than $25,000 (the expected earnings of a high school graduate) six years after enrollment.

- At the average four-year public college, 22.2% of students who had taken out loans were unable to begin paying down their loans three years after leaving school. By comparison, the mortgage delinquency rate peaked around 10% during the height of the 2010 housing crisis.

- Price has little relationship to outcomes. Low-performing schools actually charged higher net tuition than schools with superior outcomes.

- The worst-performing schools tend to have higher concentration of Pell grant recipients.

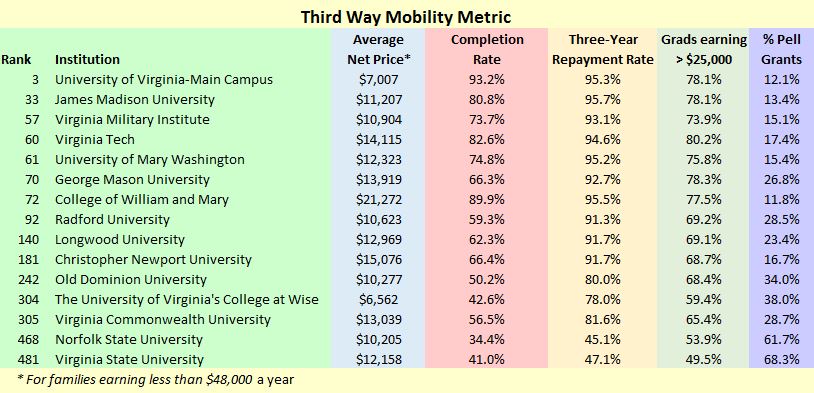

Third Way compiled a “mobility metric” for 535 public, four-year institutions incorporating a variety of factors: net price (the amount paid after financial aid has been factored in) for students from families making less than $48,000 a year; the percentage of students who receive Pell grants (typically from families earning less than $50,000 a year); completion rates within six years; percentage of students receiving financial aid earning $25,000 annually six years after enrollment; and the repayment rate on federal loans three years after students leave school.

“With outcomes like these,” concludes the report, “it is clear that simply addressing the rising cost of college isn’t sufficient to ensure students are being equipped with the degrees and skills they need to succeed.”

Bacon’s bottom line: I highlighted the Virginia public institutions in the table above. Overall, Virginia’s public college system fares well by this set of metrics, with the University of Virginia the No. 3 performer in the country. Eight of 15 institutions rank in the top quintile. However, two rank near the bottom, and several others have nothing to brag about.

I have criticized the University of Virginia for its aggressive tuition increases, but Mr. Jefferson’s university does deserve credit for making tuition more affordable for poor students and ensuring that its students graduate on time.

By contrast, the track record for Norfolk State University and Virginia State University, two historically black universities, is abysmal. The completion rate is low, post-graduation salaries are low, and the loan repayment rate is low. On the one hand, NSU and VSU provide an educational option for students from poor black families seeking to better their condition through higher education. On the other hand these institutions are hobbling thousands of students who fail to graduate, or fail to earn good jobs even if they do graduate, with thousands of dollars in debt that will haunt them for years.

We should ask whether these two institutions, as well as some for-profit “career schools” not listed here, do more harm than good. We should ask whether the federal government should be encouraging students to borrow heavily to attend four-year colleges when many would be better off earning community college degrees or not attending college at all. We should ask whether handing out lots of free money (Pell grants) and easy money (college loans) is alleviating poverty or making it worse. Finally, we should ask whose interests are being served — the higher ed establishment’s or the student’s — by perpetuating this massive wealth transfer.