by James A. Bacon

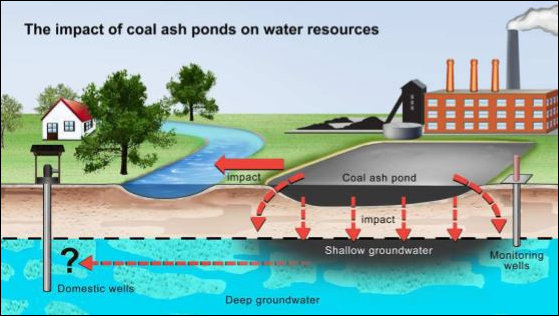

New tests and analysis conducted by Duke University add to the body of evidence indicating that heavy metals in coal ash ponds leach into the water and and make their way into surrounding water, sometimes in excess of federal standards for drinking water and aquatic life.

The researchers sampled surface water near seven coal ash pits and seeps from berms ringing the unlined ponds at seven sites in four states, including Dominion Virginia Power’s Bremo and Chesapeake power stations, and combined it with data from 156 shallow groundwater monitoring wells in North Carolina. The scientists used “forensic tracers” — isotopes of boron and strontium created in coal combustion and not found in a natural environment — to track the movement of metals from the coal ash ponds to nearby waters.

The research, which was funded by the Southern Environmental Law Center, appeared in Environmental Science and Technology, a peer-reviewed journal.

Read the study here. And read the more-comprehensible-to-the-layman coverage by the Richmond Times-Dispatch here. Writes Robert Zullo with the T-D:

At Bremo, samples were taken from Holman Creek, a leak from the ash pond wall that was running toward the river and the river itself downstream of the power plant. … One test, for example, showed arsenic at a concentration of 45.4 parts per billion, more than 45 times background levels and 4.5 times the federal Environmental Protection Agency drinking water maximum contaminant level of 10 parts per billion. Another test showed arsenic at 10.7 parts per billion.

Bacon’s bottom line: Coal Combustion Residuals, of which coal ash is one type, is the largest source of industrial waste in the United States. Yet the processes by which leachate from the coal residue works its way into surrounding waters appears not to be terribly well understood. The federal government has ordered a particular set of remedies — treat and drain the water, then cap or landfill the mineral residue — in what appears to be a state of imperfect knowledge. State governments have the authority to exceed federal standards, which environmental groups are pressing them to do. They are dealing with the same imperfect knowledge.

When the water is drained from the coal ash, the next question is what to do with the mineral residue. Dominion proposes consolidating the material on site and capping it to prevent rainwater from seeping through. Environmental groups, concerned that groundwater migrating through the ash pits could contaminate nearby waters, want Dominion to dispose of it in lined landfills — a process that Dominion says could cost rate payers $3 billion.

The Duke study is potentially important because, as the authors write in their abstract, “Given the large number of coal ash impoundments throughout the United States, the systematic evidence for leaking of coal ash ponds shown in this study highlights potential environmental risks from unlined coal ash ponds.”

We’re talking about what could be a genuine problem here in Virginia. We can quantify the very real, $3 billion cost of disposing of the coal ash in lined landfills, but it is exceedingly difficult to put a dollar value on the risk to human and aquatic life posed by leaving the mineral in capped but unlined pits. I’m not sure how we go about even conducting that analysis. I would like to think that any regulatory decisions are made after rigorous study and thought. But that’s probably too much to ask in a world in which political decisions are made under time pressure on the basis of ideology and self-interest.