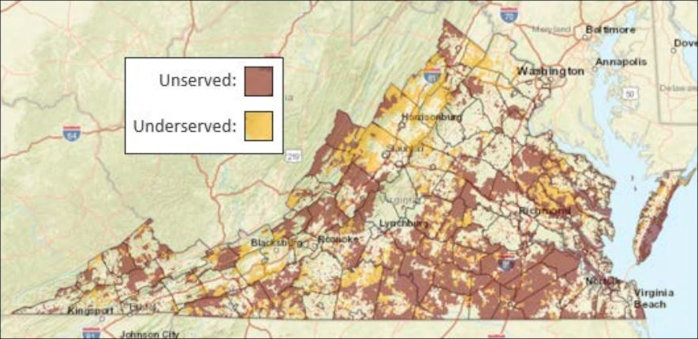

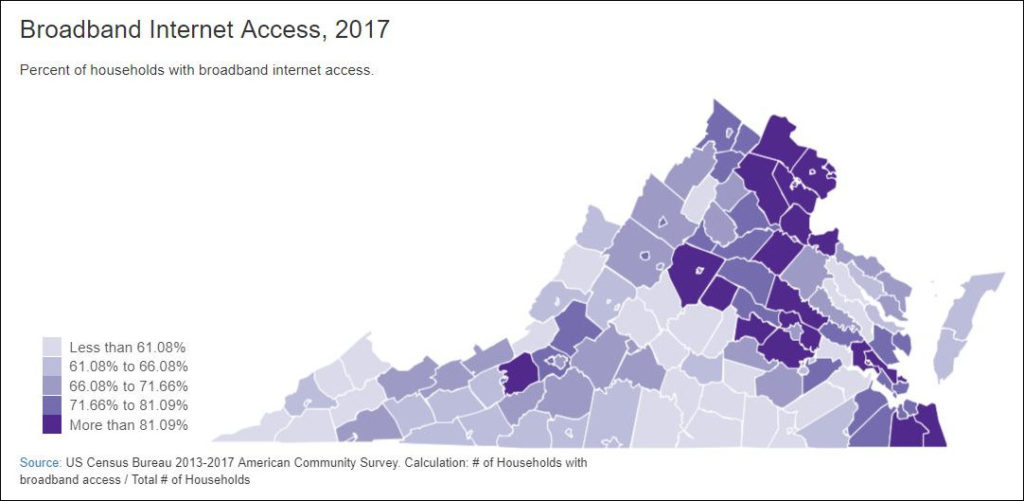

Throughout the Central Appalachian region — Virginia, West Virginia and Kentucky — community leaders have a keen understanding that they must find new industries to replace coal. And there is a near universal conviction that any hope to diversify local economies requires high-bandwidth connections to the outside world. This conviction has led to a series of initiatives, some misguided and some on target, to bring broadband to this isolated region.

Ronald Bailey with Reason Magazine has visited Central Appalachia to examine these efforts and concludes pessimistically, that they’re not accomplishing much. The article’s headline says it all: “The Noble, Misguided Plan to Turn Coal Miners into Coders: Expensive high-speed internet and job training will not transform Appalachia into ‘Silicon Holler.'”

The story begins in 1999 with the decision of Bristol Virginia Utilities (BVU) to build a fiber-optic network connecting its eight electric substations and all of the city’s public facilities. In 2002 BVU OptiNet began deploying a fiber-to-the-home network with the help of state and federal grants, tobacco settlement money, and revenue bonds — $132 million all told for 13,000 customers. (That’s a capital investment of about $10,000 per customer.) The end result:

Cash inflows from successive government grants enabled OptiNet to function like a Ponzi scheme, masking the fiscal rot at the heart of the enterprise. Eventually in 2013, an audit found extensive misuse of funds—personal trips, bribes, and kickbacks—by board members, officers, and contractors. In 2016, nine people associated with the BVU Authority, including its CEO, chief financial officer, and board chairman, were sent to prison for conspiracy and fraud. The state government’s 2016 final report noted that the OptiNet division was operating at a net loss, that this was expected to continue, and that therefore it was unlikely to generate enough cash to pay both the principal and interest owed on $45.5 million in bonds it issued in 2010.

The audit also found that the BVU Authority used an improper methodology to account for and cancel debt when it became an independent entity, and as a consequence it now owes the Bristol city utility division nearly $14 million. The auditors’ blunt assessment: “These conditions raise substantial doubt about OptiNet’s ability to continue as a going concern.”

Now a Southwest Virginia entity, Sunset Digital, has negotiated a deal to acquire OptiNet’s assets for $50 million. As the author Bailey notes, that’s a “smart move” for Sunset Digital and its owner Paul Elswick, who are backed by a Miami, Fla., based private equity firm.

Meanwhile, in nearby Dickenson County, the county also has been investing in building a fiber-optic cable network. In 2004 the board of supervisors created the Dickenson County Wireless Integrated Network (DCWIN). Next year DCWIN issued $1.5 million in bonds to build 10 cell towers. To pay off the bonds, the network had to sign up 1,500 customers. Never happened. Five years later, the county board dissolved the authority, assumed its debts, and sold the wireless network to a local company for $277,000.

Those are relatively small potatoes compared to the shenanigans in eastern Kentucky, which Bailey describes in considerable detail. The author came away impressed by some of the entrepreneurs who want to bring broadband to the region, but not so impressed by the efforts of local government officials, who don’t know what they’re doing. He calls into question the entire premise of trying to rejuvenate the economy by pumping money into highways, broadband, and other infrastructure.

It is hard to see the seeds that are supposed to someday sprout and grow into a nascent Silicon Holler.

It’s difficult to tell how many employers, if any, have decided to relocate to Southwestern Virginia due to better access to high speed data networks. As with the highway construction project before it, the internet infrastructure push has not created a detectable boom. Population in the counties covered by various government-subsidized broadband networks continues to fall, dropping from 334,000 in 2000 to 324,000 now. Between 1980 and 2000, by contrast—without any high-speed internet to speak of and with the highways uncompleted—the area’s population dropped by a smaller amount, from 336,000 to 334,000.

For more than 50 years, the feds have poured billions in job training and infrastructure funds into central Appalachia with the goal of spurring economic growth and reducing endemic poverty. There is very little to show for all that effort.

Bacon’s bottom line: I kinda sorta agree with Bailey. But not entirely. I share Bailey’s skepticism about how local governments have tried to jump-start broadband connectivity. Clearly, Bristol and Dickenson County lost a lot of money they could ill afford to lose. If local governments are going to get into the broadband business, they need to be better stewards of scarce public dollars..

But I sympathize with the desire of Southwest Virginians to salvage their economy, and I agree that having broadband connectivity is a necessary condition to achieving that revitalization. In other words, without broadband, there will never be an economic revival. Unfortunately, investing in broadband is no guarantee that new jobs and opportunities will come. It’s the ticket the region must buy to get into the game.

Hat tip: Jack Lucas

The latest wave of wireless innovation is upon us — fifth generation wireless, otherwise known as 5G. The technology will multiply download speeds by 10 times or more, allowing wireless carriers to compete with cable companies for high-speed Internet access. As former FCC trade commissioner Robert McDowell writes in the

The latest wave of wireless innovation is upon us — fifth generation wireless, otherwise known as 5G. The technology will multiply download speeds by 10 times or more, allowing wireless carriers to compete with cable companies for high-speed Internet access. As former FCC trade commissioner Robert McDowell writes in the