by James A. Bacon

Maybe the Internet is allowing innovation and creativity to break free from the confines of geography after all. Economists conventionally argue that large metropolitan areas are better incubators of inventions and innovations than smaller cities and rural areas. However, a new study, “Cities and Ideas,” by Mikko Packalen and Jay Bhattacharya, finds that the relationship between city size and inventiveness is not as strong as it once was.

I partially jest when I refer to the impact of the Internet. In the 1990s, starry-eyed dreamers theorized that the Internet would enable people to plug into global commerce from a mountain cabin or small town coffee shop. As rural America continues to empty out and population migrates to the bigger cities, that promise now seems a cruel joke. But something is changing. As Packalen and Bhattacharya demonstrate, big cities are far less dominant than they were a century ago. Furthermore, the geographic de-concentration of invention long preceded the rise of the Internet. Other trends — the proliferation of telephones, the spread of roads and the automobile, the rise of land-grant universities in out-of-the-way places — may have played equally critical roles in diffusing the capacity for invention.

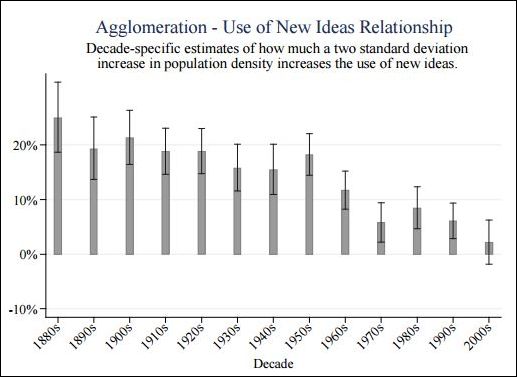

Scholars first theorized about the correlation between city size and innovation, which they called an “agglomeration effect” in the 1920s. There was a solid basis for the theory then — large cities were the dominant incubators of innovation; rural areas were backwaters. But even as agglomeration-effect theory became more deeply rooted among scholars studying urban geography, the reality upon which the theory was based was steadily eroding.

To measure invention, Packalen and Bhattacharya built a database of U.S. patents between 1836 and 2010, identifying the inputs for each patent from previous patents, how old those inputs were, and where the inventions took place. The study gives great weight to the age of the patents, distinguishing between patented inventions that draw upon new ideas and inventions that draw upon older ideas. The authors explain:

If we find that inventors in large cities build on fresh ideas more often than inventors in smaller cities, the evidence would quantify a specific benefit to locating inventive ideas in large cities. On the other hand, if we find that inventors in large cities are no more likely to try out new ideas in their work than inventors in smaller cities, the evidence would suggest that location may be largely irrelevant for inventive performance.

The dominant theory in academia today is that size and density matter. The bigger and denser a metropolitan region, the greater the number of people who can interact on a face-to-face basis. Proximity to other people allows innovators to conceive, discuss and test new ideas, and commercialize them in the marketplace. As can be seen in the chart above, which compares idea inputs of patents between cities in the 95th and 50th percentiles (large versus midsized cities) that was certainly true a century ago. But the dominance of big cities has declined, despite a few ups and downs, since then. Today, adjusted for the margin of error, there is very little difference at all.

Bacon’s bottom line: I am not equipped to dissect the statistical methodology employed to reach these conclusions, although I do have a couple of questions. Why the focus on the newness of the ideas behind the patents? Are patents based on newer ideas necessarily more consequential than those based on older inputs? Why not measure the frequency of patents? Surely the number of patents, adjusted for population size, is also an important indicator — perhaps the most important indicator — of inventiveness.

Those questions aside, “Cities and Ideas” would seem to provide hope for America’s small towns and rural regions. In this blog, I have frequently written about the tremendous disadvantages facing smaller communities when competing with big cities for human capital and corporate investment. The odds seem hopelessly stacked against the little guys. But if it turns out that it’s just as easy to keep up with the latest technology in Small Town USA as it is in Big City USA, a lot of people — and that includes me — may have to adjust their thinking.