About Bacon’s Rebellion

Bacon's Rebellion is Virginia's leading independent portal for news, opinions and analysis about state, regional and local public policy. Read more about us here.

Holy, Moly! Private-Sector Passenger Rail in Va.?

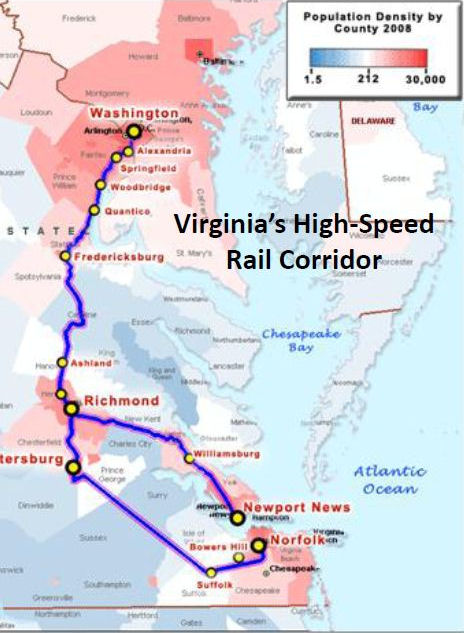

While the McDonnell administration seeks funding to extend Amtrak passenger service in Virginia, Hampton Roads planners are pushing European-style high-speed rail from Norfolk to Richmond and Washington -- financed largely by the private sector.

While the McDonnell administration seeks funding to extend Amtrak passenger service in Virginia, Hampton Roads planners are pushing European-style high-speed rail from Norfolk to Richmond and Washington -- financed largely by the private sector.

by James A. Bacon

There's an inherent difficulty in getting High Speed Rail to Virginia. Amtrak leases its rail lines from freight railroads. Freight rail tracks are designed to handle heavy-laden cargo trains, not fast-moving passenger trains, effectively limiting speeds to about 75 miles per hour. But 75 mph is barely faster than vehicles can travel the Interstate. Motorists stick to their cars and Amtrak is hard pressed to generate enough fares to pay its operating costs, never mind the capital cost of upgrading the rail lines.

But what if... What if a public-private partnership built its own line from Norfolk to Richmond and Washington that didn't have to share the rail with freight trains? Such a partnership could design the rail line for passenger trains to run as fast as 150 mph. In that case, says Alexander E. Metcalf, president of Transportation Economics & Management Systems, Inc., a passenger rail consulting firm, the economics would change dramatically.

The faster a train can travel and the more frequent its schedule, the greater the number of people who want to use it and the more they are willing to pay for a ticket. As a rule of thumb, says Metcalf, a 110-mph train can contribute fares equivalent to five to ten percent of its capital cost. A 150 mph train can kick in 20%. Also, as demonstrated repeatedly in Japan and Europe, stations serving fast trains act as magnets for development. Office landlords charge higher leases, property values rise, and, if some of that value can be captured through a special tax district or other means, it could be possible to pay even more of the the rail line's up-front capital cost.

Unbeknownst to most Virginians, Metcalf says, the Norfolk-Richmond-Washington route may be the best prospect in the country for high speed passenger service outside of the densely populated Washington-New York corridor. Driven by the rising price of aviation fuel, airlines are retreating from short flights. Meanwhile, rising gasoline prices and increasing Interstate congestion make long car trips increasingly expensive and inconvenient. The middle-range distance between Norfolk and Washington is the sweet spot where rail is most competitive.

While Virginia rail policy has achieved some notable successes, such as extending the slower Amtrak service from Washington to Lynchburg -- a profitable route, incidentally -- and from Norfolk to Richmond, the McDonnell administration has focused its high-speed rail initiatives mainly on the Washington-Richmond-Raleigh corridor, leaving Hampton Roads out of the loop.

However, the Hampton Roads Transportation Planning Organization has been building a case for a high -speed Washington-Richmond-Norfolk route. For the military-dependent region, a fast rail connection is a strategic economic-development imperative. Providing military personnel the ability to reach the Washington area, participate in a meeting and ride back in a normal work day would make Hampton Roads more competitive with other regions as the Department of Defense grapples with budget cuts and base closings.

"A two-hour trip to D.C. changes the way Hampton Roads does business," says Dwight Farmer, executive director of the HRTPO. "We become a suburb of Washington, D.C. ... If you downsize the military, where would you consolidate [operations]? Hampton Roads!"

According to the Preliminary Vision Plan published in 2010, there could be as many as 14 stations between Norfolk and Washington, D.C., including the terminus at Union Station. The route would swing south of the James River, running through Suffolk and Petersburg before stopping at Main Street station in downtown Richmond. Then the route would run north to Washington, with at least one major stop in the Pentagon/Reagan National Airport area. Some trains would halt at smaller stations along the way but others would blast through without stopping.

Metcalf, a United Kingdom native who worked on British Rail's Channel Tunnel project, came to the United States when the rail company was pitching a public-private partnership for a Chicago-Detroit high speed rail route in the 1980s. State and local government never coughed up sufficient funds to make it work, he says, but the project did demonstrate that the private sector had a keen interest in U.S. passenger rail.

Metcalf settled in Frederick, Md. "I've never been able to leave America since," he says. Now he's doing work for the Hampton Roads TPO.

Part of the difficulty jump-starting high speed rail in Virginia is the necessity of cooperating with the freight railroads, CSX Corp. and Norfolk Southern, which own the rail lines. Freight railroads like flat tracks that can better accommodate heavy loads. Passenger railroads prefer slightly banked tracks -- utilizng the same principles of physics as a race car speedway -- that can handle fast-moving trains as they go around curves.

The optimum solution, suggests Metcalf, is for a public-private partnership to acquire the right-of-way for its own track in the wide-open spaces between cities. The land is cheaper and the partnership can design the track for speed, including grade separations to avoid conflicts with local traffic. Passenger trains could merge with the freight line in urban areas where land is expensive and the train has to slow its speed anyway.

The Norfolk-Washington corridor is comparable in length and population to a proposed Miami-Orlando route, which has attracted considerable private-sector interest, says Metcalf. "If we come up with a good plan, we think there could be a franchise competition. We think there could be a lot of bidders."

Essential to the plan is devising a "value capture" mechanism to tap the increased property values that take place around rail stations. The faster the train and more valuable the service, the greater the jump in property values. "We've see it in Japan, Europe and Britain," Metcalf says. "There is massive value creation around the stations. ... This happens when you build major terminals within cities. The developers know all about it."

One way to help finance the $6 billion to $7 billion capital cost would be to create special tax districts around the stations. Landowners would pay the added taxes from the higher rents they enjoy on their property. Local governments can add juice by increasing density around the stations. Another possibility is that local governments underwrite their share of the construction cost by issuing bonds and paying the debt service directly from higher tax revenues resulting from increased property values. Metcalf doesn't endorse any particular approach. He simply states that there are options.

Even under the most optimistic scenario, though, a federal government contribution would be necessary. If the private-sector could chip in 50% to 80% of the capital cost, the project would quickly move toward the top of Uncle Sam's list of funding priorities, Metcalf says.

While Hampton Roads is the driving force behind the rail project, the proposal would be a boon to Richmond, too. Richmond's business community sees tremendous benefits in linking to the fast-growing economy of the Washington region, as well as the Washington-New York-Boston corridor. High-speed rail would help Richmond's professional services sector strengthen ties to clients in Washington and points north. In essence, high-speed rail would make Richmond and Hampton Roads the southern anchor of one of the world's largest, most dynamic mega-regions.

The Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transportation is not actively involved with the initiative. "Short term, DRPT is currently utilizing state funds to extend conventional-speed passenger rail to South Hampton Roads by mid December 2012," says Amanda Reidelbach, communications director for DRPT. "By incrementally developing state funded conventional-speed intercity passenger rail, Virginia is positioning corridors to be eligible for federal funds for higher-speed rail, when or if funds ever become available."

Due to the high cost of developing the kind of high-speed rail envisioned by Farmer and Metcalf, project development will require a federal funding partner, which entails a "multiple decade, multi-step federal program process." DRPT will continue to work, Reidelbach says, to "incrementally advance" Virginia segements of the Southeast High-Speed Rail Corridor. In that corridor, which currently is undergoing environmental review, a trunk line runs from Richmond to Raleigh through to Atlanta. A side line runs from Richmond to Norfolk.

Farmer is optimistic that the Norfolk-Richmond-Washington plan could move to a timetable measured in years, not decades. The Hampton Roads TPO, he says, awaits a definitive study from Metcalf by the end of 2013. Then the feds must fund a Service Development Plan, which pave the way for winning federal funding. Figuring out how to capture the economic value created around stations might be sticky, especially for local governments that have little experience with such projects. But generating interest from the private sector will be fairly easy, predicts Metcalf. Virginia's experience with public-private partnerships should give the state an advantage in cobbling together a deal. "It will be an uphill battle," he says, "but getting there will be worth the effort."

=====================

This article was made possible by a sponsorship of the Piedmont Environmental Council.