Four companies are talking about building gas pipelines through Virginia. How many are needed — and who decides?

Four companies are talking about building gas pipelines through Virginia. How many are needed — and who decides?

by James A. Bacon

How many natural gas pipelines does Virginia need? A lot of people are asking that question as two projects — the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and the Mountain Valley Pipeline — are actively developing routes between the Marcellus shale gas fields to the northwest and fast-growing markets to the south. Meanwhile, the Williams Companies, owner of the giant Transco pipeline, is talking up the Appalachian Connector, and Columbia Gas Transmission says it might upgrade an existing pipeline terminating in Northern Virginia.

All told, the four projects would add a capacity of 6.8 billion cubic feet per day, or roughly 200 billion cubic feet monthly. While much, if not most, of that gas would be destined for markets outside Virginia, that’s still a tremendous amount of capacity. By way of comparison, existing pipelines deliver to Virginia between 20 billion and 60 billion billion cubic feet monthly, depending on the time of year.

The question of how much is too much has become an urgent one as landowners in the path of the proposed pipelines resist survey crews from entering their property and vow to resist acquisition of their land by eminent domain. To acquire right of way using eminent domain, they say, companies must articulate a compelling public need to the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). While there may be a need for some new pipeline capacity, they contend, it’s hard to justify all four projects.

“We’ve got a big infrastructure build-out proposed,” says Greg Buppert, staff attorney for the Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC), who is tracking the issue. “My suspicion is that some but not all of this capacity is needed. There is even a possibility that existing infrastructure can meet the need.”

But some say the market is self-limiting. Pipeline companies won’t spend billions of dollars adding new capacity unless they get enough long-term contracts to ensure they can pay for a project. If there is insufficient demand to support all four pipeline projects, all four pipelines will not get built.

For decades, Virginia has relied mainly upon two companies, the Williams Companies and Columbia Gas, to deliver gas to the state. Williams operates the high-capacity Transco pipeline — energy journalist Housley Carr refers to it as “the gas-transportation equivalent of an eight-lane highway”– connecting the Gulf of Mexico gas fields with New York by way of Virginia and other Atlantic Coast states. Columbia Gas runs a parallel pipeline highway west of the Appalachias, which serves a multi-state distribution system that feeds into Virginia via West Virginia.

Traditionally, most gas from both pipelines has come from the Gulf of Mexico. But fracking has turned North American energy economics topsy turvy. Gas fields tapping the Marcellus and Utica shale deposits in West Virginia, western Pennsylvania and Ohio are reputed to contain as much natural gas as Saudi Arabia. Marcellus gas is abundant and cheap, and gas pipeline companies have been scrambling to develop new markets, mostly in the U.S., but also for foreign markets by means of Liquefied Natural Gas.

The explosion in supply coincides with a surge in demand, especially from electric power companies. In two major waves of regulation in recent years the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has mandated power companies to reduce their toxic emissions from coal-fired power plants and then, with final rules issued early August, to reduce emissions of carbon dioxide by 32% nationally. In both cases, utilities are shifting en masse from coal to natural gas. While renewable sources such as solar and wind power are expected to gain electricity market share, industry officials say they must be backed up by gas generators to take up the slack when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow, so demand growth for renewables actually supports demand growth for natural gas. Meanwhile, gas companies foresee a kick in long-term demand from a growing population and economy, especially among manufacturing operations seeking to tap some of the world’s lowest cost energy and chemical feedstock.

“Virginia is in need of new natural gas transmission that can get these new reserves to the parts of Virginia that need it the most,” says Christina Nuckols, deputy communications director for Governor Terry McAuliffe. “Hampton Roads is considered an energy cul-de-sac where natural gas capacity constraint has been an issue for years. Particular counties in central and southern Virginia also have reported on numerous occasions that they lose out on manufacturing-related economic development opportunities almost immediately because they cannot provide access to natural gas.

“With any new market opportunity, there are going to be a number of companies looking to find success,” she says. “All of these proposed pipeline projects are recognition that Virginia is in need of additional natural gas capacity and the infrastructure to provide it. It remains to be seen which projects will get approval from the appropriate entities.”

Here are the major projects proposed for Virginia:

Atlantic Coast Pipeline. The Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP) is a partnership of four major energy companies: operating partner Dominion Resources, Duke Energy, AGL Resources, and Piedmont Natural Gas. The pipeline would originate in Harrison County, W.Va., and run 550 miles to southern North Carolina, with 70-mile spur to Hampton Roads. Capacity would be 1.5 billion cubic feet per day. The ACP would interconnect with the Transco pipeline in Buckingham County, Va., allowing gas to flow north or south on the Transco system from there.

When describing their investment in the $5 billion project, Dominion officials emphasize the growing electric utility market for natural gas. Since he took on his job as CEO of Dominion Generation Group, says David Christian, the company has sold, closed or converted to gas 21 coal units nationally, several of them in Virginia. To take up the slack, Dominion opened a new gas-fired unit in Warren County, Va., in 2014 that burns roughly 250 million cubic feet of gas per day. Dominion is building another gas-fired plant just like it in Brunswick County, Va., which will burn a comparable amount, and has plans, if approved by the State Corporation Commission, to build another similarly scaled plant in Greenville County, Va., by 2018. Some of that gas can be reliably supplied with existing pipelines but not all.

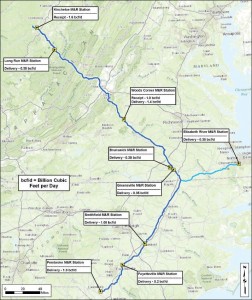

This map shows the main delivery points in the proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline. Click for detailed image.

Dominion has contracted in binding agreements to take roughly 300 million cubic feet per day of gas from the ACP pipeline. Duke Energy, which is undergoing a similar transformation, has committed to take about 725 million cubic feet per day, while Piedmont Natural gas will take 160 million cubic feet, Virginia Natural Gas 75 million cubic feet, and the Public Service Company of North Carolina 100,000 million cubic feet, according to a May 2015 data resource report. (The resource report measures gas quantities in decatherms. A decatherm contains roughly the heat content of 1,000 cubic feet of natural gas. I have translated the numbers into cubic feet to make the numbers in the article easier to compare throughout.)

In total, 91% of the pipeline capacity is contracted for. The unsubscribed capacity will be awarded to other parties in accordance with FERC policies. While the ACP cannot say where that gas might be shipped, the report states emphatically that the pipeline “is not designed to export natural gas overseas.” The map above shows where the gas will be delivered.

While there is still spare capacity in the existing pipeline system, Dominion foresees a need for additional capacity to meet continued demand growth. “We project the demand curve, add a reserve margin [for safety], and we see a gap in the future,” says Christian.

Another advantage of having another pipeline, say Dominion officials, is the ability to diversify sources of gas supply. Right now, Marcellus gas is cheaper than the Gulf of Mexico gas that Dominion burns. There’s no guarantee that Marcellus prices will stay lower than Gulf prices, especially if exports of Liquefied Natural Gas take off, but to Dominion’s way of thinking, two sources are more stable and reliable than one. Another advantage is the ability to draw upon an alternate source of supply should the transport of gas from offshore drilling rigs in the Gulf Coast be disrupted, as it was after Hurricane Katrina; gas prices spiked until the Gulf infrastructure could be restored. A Dominion-commissioned study by ICF International concluded that consumers and businesses in Virginia and North Carolina would save an estimated $377 million a year in lower energy costs over 20 years thanks to the pipeline.

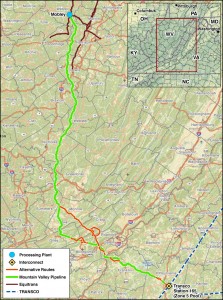

Mountain Valley Pipeline. The Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP) is a partnership of four gas companies: operating partner EQT Corporation, NextEra Energy, WGL Midstream and Vega Midstream. The pipeline would run 294 miles from northwestern West Virginia, skirt south of Roanoke, and hook into the Transco Pipeline at compressor station 165 in Pittsylvania County.

The MVP, expected to cost between $3 billion and $3.5 billion, has secured 20-year contracts to provide at least 2 billion cubic feet per day of firm transmission capacity. With a connection to the existing Equitrans system in West Virginia, the company says, MVP will address infrastructure constraints holding back development of natural gas in the Marcellus and Utica shale plays, while also providing supply diversity to natural gas consumers across the Southeast.

Historically, Transco has moved about 10% of the nation’s natural gas supply. But as new pipelines flood New York and other northern markets with cheap Marcellus gas, Transco likely will lose market share there. While Transco mainly moved gas moved south to north in the past, parent company Williams is working to make the pipeline bi-directional. This new flexibility allows the MVP pipeline to reach a much wider market than it could on its own.

One of the MVP partners, WGL, already moves significant volume on Transco’s mainline pipeline. In December, according to the Roanoke Times, the company announced a sales agreement to export natural gas to India via Dominion’s Cove Point Liquefied Natural Gas facility in Maryland, which is served by Transco, spurring controversy in western Virginia where local citizen groups have contested the public necessity of the pipeline. However, in a May 2015 hearing, Paul Friedman, FERC environmental project manager, insisted that Mountain Valley gas would not be exported. Said he:

That will not happen, and I’ll explain why: Mountain Valley has not applied to either the FERC or the U.S. Department of Energy for permission to export natural gas. Without those applications and our permission, they cannot export natural gas.

MVP is in the process of determining the optimum route for the pipeline. The company is conducting civil survey work to identify sensitive environmental and cultural sites that need to be avoided, says MVP spokesperson Natalie Cox.

WB XPress. Columbia Pipeline Group which transports an average of 3 billion cubic feet per day of natural gas through a 10-state pipeline network, is proposing a major upgrade to an east-west pipeline between Virginia and West Virginia. The project would boost capacity by 1.3 billion cubic feet daily through the installation of a compressor station in Fairfax County, compressor upgrades along the system, construction of 26 miles of replacement pipeline in existing corridors and 2.9 miles of new pipeline. The stated purpose is “to meet growing market demands in western West Virginia and northern Virginia.”

Because the WB Xpress project would utilize existing rights of way for the most part, it would avoid the challenge encountered by the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and Mountain Valley Pipeline of requiring land surveys and right-of-way acquisition.

In July, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission began soliciting public comments in preparation of an environmental assessment.

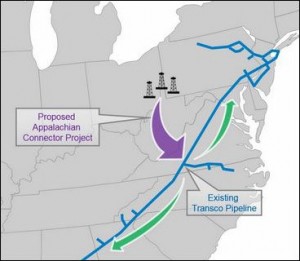

The Appalachian Connector. The Williams Cos., owner of the Transco pipeline, is in the “early stages” of performing desktop analysis of running a pipeline between Clarington, Ohio, and Transco’s compressor station 165 in Chatham, Va. The pipeline, as currently envisioned, would move up to 2 billion cubic feet of gas per day by late 2018. The project is unique, says that company, in that it is the only project currently proposed that would tap the western Marcellus and Utica regions to access the Transco pipeline. The route has not yet been identified, and the company has not yet started the process of conducting field surveys.

The Appalachian Connector. The Williams Cos., owner of the Transco pipeline, is in the “early stages” of performing desktop analysis of running a pipeline between Clarington, Ohio, and Transco’s compressor station 165 in Chatham, Va. The pipeline, as currently envisioned, would move up to 2 billion cubic feet of gas per day by late 2018. The project is unique, says that company, in that it is the only project currently proposed that would tap the western Marcellus and Utica regions to access the Transco pipeline. The route has not yet been identified, and the company has not yet started the process of conducting field surveys.

“We’re evaluating market interest,” says Chris Stockton, a spokeperson for Williams Transco. “We’ve had some interest — customers have come to us about connecting to that Utica supply. We’re determining if there’s enough market support. We can’t build a pipeline on spec. We need contracts from customers willing to pay for this multibillion dollar project.”

How much is too much? The Southern Environmental Law Center is skeptical that a need for all this capacity can be justified. All of a sudden, four big pipeline projects have sprung to life in the past year or so, says Buppert, the SELC attorney following the issue. SELC got involved because the Atlantic Coast Pipeline would run through the George Washington National Forest, which SELC has expended considerable resources to protect from industrial development.

“FERC is supposed to balance the need against the harm and decide whether or not to approve the project,” Buppert says. “A company can come in and say that it has a bunch of contracts, and FERC says, ‘Great, we can check the box for need, and that’s the end of the analysis.’ … My suspicion is, the need won’t justify all the projects that have been proposed. We have engaged an expert firm to answer that question.”

Buppert thinks there is an opportunity to persuade FERC to do something it has never done before — examine more than one project at a time. “Usually, FERC looks at its projects in isolation,” he says. “That might have worked when pipelines were rare occurrences. I think we can make the case with these four projects in Virginia that the agency needs to look at these in a more holistic way. If there’s some infrastructure build-out required, identify the optimal way to do that — the least harmful route.”

Some proposed pipelines may be able to utilize more existing rights of way than others, says Buppert. “What we’re pushing for is a holistic vision for pipeline development in the whole region. … You wouldn’t build highway infrastructure this way. Pipelines could use effective planning as well.”

But others argue that market forces will minimize the risk of excess capacity getting built. Pipeline companies require major up-front commitments from customers before sinking billions of dollars into a project. If those commitments are not forthcoming, a pipeline will not get built.

Last year Spectra Energy Pipeline announced that it was evaluating an interstate gas pipeline to deliver up to 1.1 billion cubic feet daily to markets between Pennsylvania and North Carolina, including Virginia, a project that was seen as competing with the Transco pipeline. But Spectra suspended development of the project, says spokesman Arthur Diestel. Confidentiality agreements prevent him from explaining why, he says.

“There’s no way all four [Virginia] pipelines will get built,” says the former CEO of a Virginia-based gas trading company, who asked to go unnamed for personal reasons. “Well into the process [one or more players] may decide to suspend further development of the project because they haven’t been able to get a full commitment. It’s a gut feeling — it just doesn’t seem there’s enough demand out there to support that many.”

Of the four proposed pipelines, the Atlantic Coast Pipeline and Mountain Valley Pipeline are the farthest along in the regulatory process. Both companies are surveying land and plotting routes. The demand for natural isn’t theoretical, says Jim Norvelle, director-media relations for Dominion Energy. “Our pipeline is being built for customers who have already signed a 20-year contracts.”