Source: Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission

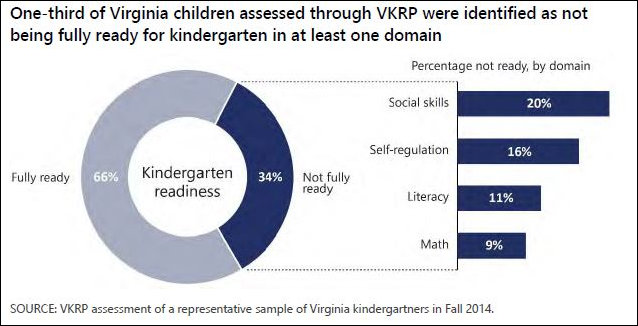

Roughly one third of Virginia children lack the social, self-regulation, literacy or math skills needed for kindergarten, finds a study on early childhood development released by the Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC).

(That estimate was derived from a representative sampling from 63 of Virginia’s 132 school systems, so a comprehensive statewide survey might yield a different percentage.)

Factors such as poverty, low birth weight, and maternal substance abuse place childrens’ early development at risk and strongly influence whether they will be ready for school. The scientific research is clear, says the JLARC report:

Very young children who grow up in — or are regularly exposed to — safe, language-rich, and healthy environments, with caregivers who support their curiosity and learning, are likely to enter school ready to learn. Conversely, children not exposed to such environments are less likely to be ready for school and are more likely to be held back, enrolled in special education classes, and perform poorly in later grades. Those same students are more likely than their peers to commit crimes, become teen parents, and rely on public assistance as they grow older. … Each of these outcomes can carry significant financial costs to government, including the state.

Virginia has 13 “core” early childhood development programs, including seven voluntary home visiting programs for expectant mothers, the Virginia Pre-School Initiative, the Child Care Subsidy Program, and two Individuals with Disabilities Education Act programs. The state spent $144 million on early childhood development programs in FY 2016; total federal, state and local spending amounted to $359 million.

An opportunity exists to improve the effectiveness of the state’s spending commitment without spending more money, JLARC concluded. “Careful attention is needed to whether programs are well designed, implemented as designed , and perform effectively.” But there is insufficient data to evaluate which programs are delivering the most bang for the buck.

Bacon’s bottom line: By all means, we should evaluate the efficacy of Virginia’s early childhood development programs and reallocate resources to programs that deliver the most value. But such fine-tuning of the existing system amounts to rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic when one out of three Virginia children is unready for kindergarten. Virginia appears to be experiencing what can only be interpreted as a slow-motion societal collapse.

Lagging childhood development is strongly correlated with poverty and other phenomena such as low birth weight and maternal substance abuse that are also strongly correlated with poverty. The percentage of Virginia’s population in poverty at present runs about 11%. Yet one-third (subject to revision if we could obtain statewide data) of children are unready for kindergarten. Why the three-to-one disparity? A big portion of the problem, I submit, is demographic: Mothers in poverty have more children than middle-class mothers do, and they have children at much younger ages.

At 64 years of age, I’m about to become a grandfather for the first time. My eldest daughter, whose baby is due in literally one or two days, is 32 years old. Like her 30-year-old sister, who wants to have children but is waiting until her family’s career and finances are in order, and like the vast majority of middle-class Americans, she waited until she completed her education, found a job, got married, saved money, and achieved financial stability. Poor people don’t hew to the same family planning logic. Although the number of teen pregnancies is declining, poor women tend to give birth at a much younger age than their middle-class peers do, and they tend not to be married. (This proclivity, by the way, applies to all races and ethnicities.)

Given the strong correlation between poverty and low literacy levels, substance abuse, single-parent households, child neglect and a host of other pathologies, it should come as a surprise to no one that the percentage of Virginia’s young children ill equipped for kindergarten is increasing. And it should surprise no one that the percentage of teenagers ill equipped to graduate from high school is increasing, and that the percentage of young adults ill equipped for college is increasing. The same problem is manifesting itself on every step of the educational ladder.

Yes, we need to treat the symptoms of this systemic problem by, among other things, helping prepare young children for kindergarten. But the same pathologies that hinder readiness for kindergarten also hinder progression to 1st grade and beyond. In the long run, the most important thing we can do is to persuade teenagers and young women that they can improve their lives by adopting bourgeois values — deferring gratification, staying sober and delaying child bearing until they have completed their education, formed a stable marriage, and found a stable job.