Few would disagree that college tuition is becoming an intolerant financial burden on middle-class families, and few would dispute that declining state support for public colleges and universities is at least partly to blame for tuition increases. What can be done to create a “stable and sustainable” funding model for public higher education in Virginia that can help stabilize tuition increases?

The State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV) threw that question into the lap of its staff, and the staff has responded. In a presentation to SCHEV’s resources and planning committee yesterday, Finance Policy Director Dan Hix and two finance staffers laid out four options for purposes of discussion.

If the answer to Virginia’s higher-ed affordability crisis is to be found through increased revenue, then one of these ideas, or a mix-and-match combination of them, could well provide the solution. But, as I opine below, the drawbacks are severe. The solution to the higher-ed funding crisis lies on the cost side, not the revenue side.

Option 1: Increase General Fund support at the rate of inflation through the 2018-20 biennium with the understanding that tuition for in-state undergraduate students will increase at the same rate.

The obvious advantage of this idea is that it would provide a stable revenue source for Virginia’s public institutions over the next biennium. “This option allows all parties involved from the state, to institutions, to students and their parents to have a predictable annual increase in base support, thus allowing for improved planning,” states the SCHEV memo.

Assuming an average annual inflation rate of 2%, the plan would raise an additional $29 million from the state General Fund and $64 million in tuition revenue, for a total of $92 million.

An obvious drawback is the risk that the General Assembly would renege on its promises, as it has in the past, if state revenues don’t match forecasts. Another is that even if lawmakers could be counted upon to deliver, colleges and universities might not want to be constrained by an inflation-linked spending cap.

Option 2: Reduce state support for graduate education by changing the current funding splits from 37% from the state and 63% from tuition to 25% and 75% respectively, and reallocate the “savings.”

This approach approach would make higher education more affordable for undergraduate students at the expense of graduate students, and it would reallocate money from larger research universities to smaller, undergraduate-oriented institutions.

Reducing the state split to 25% would raise about $39 million to reallocate to undergraduate-oriented institutions. Politically, this option might have legs. Undergraduate students are more likely to come from Virginia; graduates are more likely to be out-of-staters. Any plan that benefits Virginia families will be popular with politicians and their constituents.

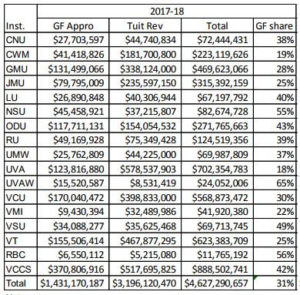

General Fund share versus tuition revenue, 2017-2018 school year. Click for larger image.

The drawback is that the impact would be highly uneven. Some institutions are much more dependent upon state support than others. Among research institutions, for example, the General Fund share ranges from 30% state support as a percentage of state support + tuition revenue at Virginia Commonwealth University to a mere 18% at the University of Virginia, as shown in the table at left.

Moreover, some institutions have a higher percentage of graduate students than others, and some have more research grants to help pay for graduate students than others. The plan would not simply create winners and losers, but lost revenue could be especially devastating to institutions lacking the market power to increase tuition revenue aggressively.

Option 3: Allow selected institutions to increase their share of out-of-state undergraduate students up to 50% of their total undergraduate enrollment.

This option recognizes that certain institutions — UVa, the College of William & Mary, and Virginia Tech most prominently — enjoy sufficient prestige in the higher-ed marketplace that they can increase tuition more aggressively for out-of-state students than they have in the past. The idea would be to allow them to increase enrollment for out-of-state students while not taking away any current spots from in-state students. Across the higher-ed system, out-of-state students pay 163% of their cost. The bigger “profit” from out-of-staters would enable the state to reduce its support by a like amount. SCHEV estimates that the shift would free up $270 million in General Fund revenue for reallocation to needier institutions.

The drawback of this option, as currently configured, is that there is nothing in it for UVa, W&M or Tech. The elite three institutions would increase their charges for out-of-state students but the profit would be distributed to other institutions. Indeed, they likely would regard this policy as a huge negative, for charging higher tuition would shrink the pool of applicants to draw from.

Option 4: Reduce state support for both undergraduate and graduate students at selected institutions by changing the current fund splits from an average of 41% from the state and 59% from tuition to 30% and 70% respectively, and reallocate the “savings.”

Translation: Reduce state support for UVa, W&M and Tech and allow them to make up the difference by raising tuition. This option would raise $91 million for redistribution to other institutions, but Tech would have to increase tuition by 14.4%, W&M by 15%, and UVa by 23.6%.

The obvious drawback is that the state’s flagship institutions would go all Kim Jong Un in response to a policy that impacted them so negatively. Even to disinterested parties, the idea of dis-investing in the state’s strongest institutions and funneling funds to its weakest institutions might not seem wise.

SCHEV staff is acutely aware of the drawbacks of its proposals. “This is not an easy document and we are not entirely easy with some of the options included here,” states the memo. “However, if the next ten years are similar to the

last ten years for Virginia public higher education, our system is indeed in peril and options such as these may be necessary to save it.”

Bacon’s bottom line: Lawmakers can’t be relied upon to keep its funding promises, and all revenue-raising options have major drawbacks. For the most part, the options simply redistribute wealth between institutions, creating winners and losers. It’s not clear that the statewide system would be any better off.

In closing comments at yesterday’s meeting, newly appointed Council chair Heywood Fralin laid out his priorities for SCHEV. He wants Council members to have greater oversight of the Virginia Plan for Higher Education (the state’s strategic plan for higher ed). And he wants to focus on three pressing issues: (1) the restructuring of higher-ed funding, (2) tying higher education to economic development, and (3) finding ways to reduce higher-ed costs.

Finding cost savings is the great unexplored frontier. SCHEV does useful work in identifying opportunities for shared services, and it monitors higher-ed’s use of space to caution against overbuilding. But, as I argued in my four-part series on higher-ed accountability, SCHEV does not monitor faculty productivity, administrative overhead, or a host of other cost drivers.

While it would be unwise for SCHEV to begin micro-managing Virginia’s colleges and universities, I suspect there would be strong political support for SCHEV to collect data, establish benchmarks, and provide boards of trustees with analysis that they’re not getting from college administrations. The General Assembly should reallocate a couple million dollars from whatever additional sum it plans to give the universities next year and beef up SCHEV’s data-collection and analytical capabilities.