Source: Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transit. (Click for larger image.)

Downstate Virginia legislators are inclined to block increased capital funding for Washington’s dysfunctional heavy-rail commuter system unless the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) undertakes serious structural reforms.

WMATA officials say they need about $15.5 billion for capital spending over the next 10 years to work through a massive backlog of deferred maintenance. Virginia’s state-government share would be about $150 million a year over and above the $200 million it allocates annually to operations and capital spending.

“I want value. I’m willing to deliver,” said state Sen. Mark Obenshain, R-Rockingham, in a meeting of the Senate Finance Committee yesterday, reports the Richmond Times-Dispatch. “But I want to see problems solved. And all too often when we talk about solving problems, the easy way to solve it is just throw more money at it. It’s a workplace problem; it’s an efficiency problem.”

Convincing constituents that giving Metro more money is a hard sell when in his district the Robert O. Norris Bridge “is literally falling into the river,” said Sen. Ryan T. McDougle, R-Hanover. “How is it that I can go to my people and say, ‘We’re going to spend money on an organization where we have no control from the state, we have no say so in the administration based on the board is put together? … There’s no way I can justify a vote to spend that kind of money for an entity that we have this little control over and is refusing to change how that structure is done.”

(For the record, the Robert O. Norris Bridge is not “literally” falling into the Rappahannock River. Transportation Secretary Aubrey Layne told the committee that the state does not even consider it to be structurally deficient.)

Ray LaHood, the former U.S. Transportation Secretary chosen by Governor Terry McAuliffe to review WMATA’s performance and governance, told the Finance Committee that he is trying to develop consensus around four areas: WMATA’s governance structure, its funding structure, its legacy labor costs, and maintenance.

The current management team has cut 1,000 of 1,300 WMATA workers, mostly nonunion employees and tightened ethics and nepotism policies. Also, said LaHood, “We’re going to try to fix the governance part so you feel you do have a voice. We can figure out how to fix your bridge and have a good transportation — Metro system — in Washington, D.C., that you can be proud of.”

Bacon’s bottom line: Obenshain and McDougle are absolutely right. Virginia should not fork over one red cent until WMATA can prove it won’t become a fiscal black hole. It appears that the new management team has taken some important steps with the nonunion workforce, but the real challenge will be extracting major concessions from the union. If it chooses to strike, the union can virtually shut down Washington, D.C. The only way — the only way — for Virginia legislators to stiffen management’s spine in a confrontation is to withhold that $150 million a year.

Even if WMATA delivers needed reforms, pumping another $150 million a year into the authority would aggravate an already lopsided distribution of rail and transit revenues.

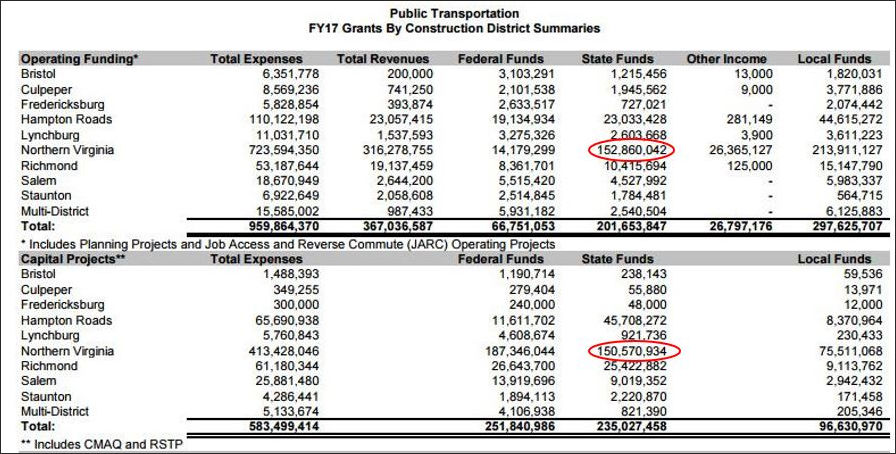

As can be seen in the Virginia Department of Rail and Public Transit’s fiscal 2017 budget atop this post, DRPT hands out a total of $437 million a year in grants to cover operational expenses and capital spending for rail, buses and handicapped transportation around the state. Of that amount, $303 million already goes to Northern Virginia. Adding another $150 million a year to that sum would favor Northern Virginia even more lopsidedly — boosting its share from 69% of the DRPT budget to 77%.

Where would the money come from? Shifting money from inside the DRPT budget would eviscerate non-WMATA programs, most of them downstate. Most likely the money would have to come from road & highway spending. Virginia Department of Transportation funds allocated to construction spending in fiscal 2017 amount to about $802 million. Taking the WMATA money from roads & highways would reduce construction spending by 19%. Not just one year, but for 10 years.

Even Northern Virginia lawmakers might balk at that.