by James A. Bacon

Northern Virginia is so much more prosperous than the Rest of Virginia that it’s difficult for we RoVians to appreciate what is happening north of the Rappahannock. But the picture isn’t pretty. Gripped by the realities of sequestration and budget cuts, the Washington region has one of the worst-performing economies in the country at the moment. And when Northern Virginia sneezes, as the saying goes, Virginia catches cold. Virginia’s current budget travails can be traced directly to NoVa’s economic ailment.

Two new reports drive home the message that Northern Virginia, the state’s economic locomotive for the past three or four decades, has experienced an unfortunate confrontation with reality.

First, CityLabs has published a list, drawn from Bureau of Labor Statistics data, listing the 10 jurisdictions that gained the most jobs in 2013 and the 10 that lost the most. Three of the 10 biggest losers — Arlington County (-1.1%, Fairfax County, -1.2% and the City of Alexandria (-1.4%) — were located in Virginia. Interestingly enough, neither Washington, D.C., nor any Maryland jurisdiction was included in the list of Top 10 biggest losers, which I would attribute to the facts that sequestration has clamped down hardest on military spending and that Northern Virginia’s economy is more military-dependent than D.C.’s or Maryland’s.

Second, the Commonwealth Institute (working in collaboration with two other regional think tanks) has published a new report, “Bursting the Bubble,” on the challenges of living in the national capital region. The broad conclusion:

Income inequality is growing. Employment levels for people without a college education are far lower than before the recession. Unemployment rates for several groups of workers, including those without a college degree, remain high. Black workers and young workers were particularly hard hit by the recession, even when compared to other areas residents with similar education levels. The high cost of living in the region is pushing many families to spend more than they can afford on housing, while others trade more affordable housing for long and expensive commutes.

The region has many successes worth celebrating. But broadly shared prosperity is not one of them.

College-educated workers are earning more than before the recession; everyone else is earning less. States the report: “While wages are rising at the top and declining at the bottom nationwide, the divergence is more extreme in the national capital region.”

“Bursting the Bubble” looks at a longer time-frame than the CityLabs article — the period from 2007 to 2012. Over those five years, which includes the Obama administration’s economic stimulus phase and ends before the CityLabs data picks up, public administration jobs (which disproportionately hires college grads) increased by 40,000 jobs while the construction sector (with mostly less-than-college grads) lost a comparable amount.

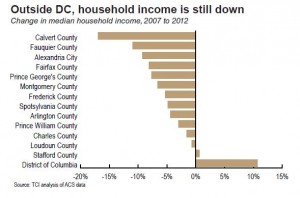

The wage growth that did occur was overwhelmingly concentrated in Washington, D.C. Every other jurisdiction (but Stafford County) saw median incomes decline.

The wage growth that did occur was overwhelmingly concentrated in Washington, D.C. Every other jurisdiction (but Stafford County) saw median incomes decline.

These employment and income trends make life especially hard for the poor. Between the high cost of housing, the high cost of child care and the long commutes, families need higher incomes to stay out of poverty. Adjusted for living costs, the region’s poverty rate is 13.4%, only a little lower the nation’ adjusted poverty rate of 15.3%.

The highest-cost housing (ranked by median home sales prices in 2012) was located in the metropolitan core — Arlington County the highest, followed by Alexandria, Washington, D.C., and Fairfax County. (It would be interesting to see a ranking based on the cost of housing per square foot.) Many homeowners are still struggling, especially in heavily African-American jurisdictions in Maryland’s Prince George County. Three percent of mortgages in the metro’s Maryland jurisdictions are in foreclosure compared to o.5% in Virginia.

Bacon’s bottom line: There’s only so much that state and local government officials can do to counteract the inevitable squeeze of federal government spending. Uncle Sam’s long-term budget crisis is far from over. The federal government will continue to be a drag on the regional economy for a long, long time. While there is a reasonable prospect that all the super-smart people who moved to the region will manage to reinvent the economy along more entrepreneurial, private-sector lines, that adjustment will take years to occur.

In the meantime, Virginia has a large backlog of transportation and infrastructure projects conceived during Northern Virginia’s go-go years. Some, like the Silver Line to Dulles, will proceed; nothing is likely to derail them. Others, like the proposed Bi-County Connector, which is part of a larger western bypass, have considerable institutional momentum but may be possible to block. It is more essential than ever that Northern Virginia authorities be cautious about loading up on debt to finance projects predicated upon the endless population and economic growth that seemed so inevitable back in the mid-2000s.

I have little confidence, however, that prudence will prevail. If anything, we could see the opposite. Governor Terry McAuliffe has signaled that he looks favorably upon the Bi-County Connector in a bid to stimulate air cargo growth at Washington Dulles International Airport. Still, we can always hope that state funds will be focused on projects, big or small, demonstrating the highest return on public investment. Rolling the dice on speculative ventures like Dulles air cargo won’t restore the region’s prosperity. Investing funds where they will achieve the greatest improvement to mobility and access is the best way to get NoVa moving again.