by James A. Bacon

In morning testimony before the General Assembly, a state auditor provided a detailed breakdown of how the University of Virginia cobbled together its controversial $2.2 billion Strategic Investment Fund: UVa was in full compliance with the Code of Virginia, and all of its monies have been properly accounted for over the years.

To label the Strategic Investment Fund a “slush fund,” as former Rector Helen Dragas had done in a Washington Post op-ed was “a little bit of a mischaracterization,” said Eric M. Sandridge, the audit director in charge of higher education programs for the Department of Public Accounts. “The university was allowed to do what it did.”

While the term slush fund has a connotation of illegality, Dragas said in submitted remarks, she did not mean to imply that UVa had done something illegal or “nefarious.” Rather, she said, “It was in view of these facts … that a small group of people went behind closed doors to discuss how to spend large sums of public money for other-than-originally-intended purposes … that the term slush seemed to fit.” (Dragas did not deliver her remarks in person because of a personal commitment of long standing.)

While Sandridge’s account supported the narrative maintained by UVa officials about the origin of the fund, he stated that his audit did not inquire into the legality under the Freedom of Information Act of a closed Board of Visitors session in which the fund was discussed, nor did it address the appropriateness of the university’s policy.

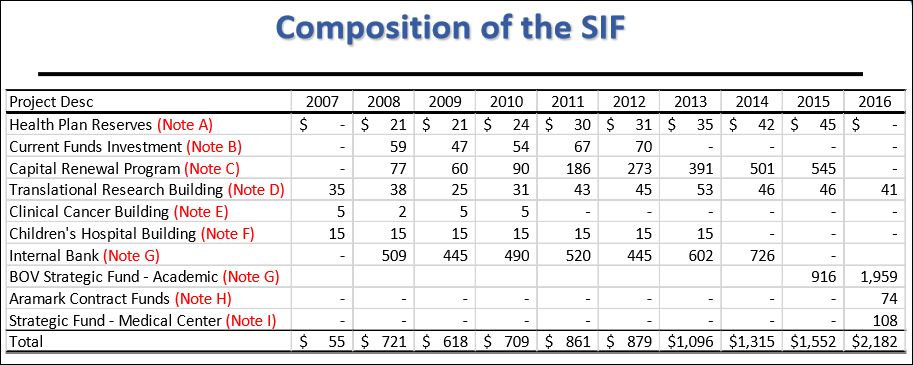

From the beginning of the controversy, which originated when Dragas first revealed the existence of the Strategic Investment Fund, UVa maintained that the fund was created by aggregating discrete reserves of money plus the investment returns on that money. By moving the money from miscellaneous pots where they were generating little income, the university consolidated them into a pool that could be invested more profitably in longer-term holdings by the University of Virginia Investment Management Company (UVIMCO).

Sandridge provided the first detailed breakdown of those money sources:

- Capital Renewal program. UVA bills university departments on a regular basis to cover future lump-sum bond payments rather than bill them at the last minute when the payments come due. This source added up to $545 million in 2015.

- Health plan reserves. The university sets aside a multimillion-dollar reserve as part of its health care self-insurance program. This amounted to $45 million in 2015.

- Internal bank. The university maintains a fund to balance the daily cash flow needs of all its operations. In 2015 this amounted to $916 million.

- Ivy Foundation. This money, a $45 million gift, was set aside for three major building projects. Upon completion of the projects, any remaining monies will be used to set up an endowment and moved out of the Strategic Investment Fund.

- Aramark Dining Services. In a 20-year contract with Aramark Dining Services, the university received a $74 million grant to use at its discretion. However, the university must repay an unamortized balance should the agreement terminate before 2034.

None of these funds came from cost-cutting initiatives as I had improperly deduced from a reference that Rector William H. Goodwin made to “efficiencies in operations.” Rather, it appears that the university administration identified funds that were sitting around collecting dust and pooled them in such a way as to create a large, investable pool of capital. Over nine years, the university has earned $575 million through this strategy.

Where does the $100-million-a-year number come from? University officials have said that they expect the Strategic Investment Fund to generate about $100 million a year that could be spent on university advancement. Sandbridge explained how that number was devised. UVIMCO’s long-term investment pool has returned more than 10% annually over five-, ten- and twenty-year periods. Assuming a comparable return on investment on $2.2 billion in the future, UVIMCO could earn more than $200 million a year. Using the same policy as the university endowment of spending no more than 4.6% a year, that would provide $100 million to spend while retaining a somewhat larger amount in order to grow the investment pool.

Bacon’s bottom line: University officials deserve praise for devising a way to maximize the value of more than a billion dollars in under-utilized cash. The financial engineering, which entailed lining up $300 million lines of credit from four banks, is a genuine financial innovation that other universities may be able to emulate.

Two issues remain. The first is transparency. It has taken two months and a state audit to provide a full explanation to the public. What took so long? As Dragas asked in the testimony she submitted:

As the board took actions to restructure debt, authorize lines of credit, and modify liquidity policies — all of which were typical governance activities in large, financially complex institutions — never were we told that these actions were related to directing $2.3 billion to rankings pursuit or given the alternative of considering them in the service of tuition reduction. … The University has yet to produce documentation or recordings showing otherwise.

The second question is how the $100 million a year should be used. The Board approved using the funds to advance the strategic goals outlined in the Cornerstone Plan, essentially a strategic plan to bolster the prestige of the university. Dragas suggests that the money could have been used to offset aggressive tuition increases. Many legislators and members of the public would agree.