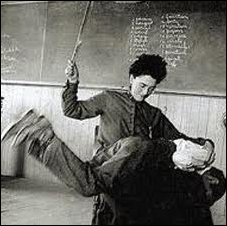

It seems intuitively obvious that allowing students to “act out” in the classroom disrupts teaching for the students who want to learn. But it’s impossible to tell from anecdotal information what effect the disruption has on student achievement and graduation rates, much less upon future earnings.

In “The Long-Run Effects of Disruptive Peers” published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Scott E. Carrell, Mark Hoekstra and Elira Kuka have tapped longitudinal data from Alachua County, Fla., to demonstrate that the negative effects of disruptive behavior in elementary school is measurable and long lasting.

“With respect to college attendance, our findings indicate that one year of exposure to a disruptive boy peer reduces college enrollment by 0.2 percentage points,” the authors write. “We estimate that one year of exposure to a disruptive peer in elementary school reduces the present discounted value of classmates’ future earnings by around $100,000.”

While not as important as teacher quality in explaining differential outcomes, the authors argue, the presence of disruptive students is nevertheless a significant factor, accounting for 5% to 6% of the rich-poor earnings gap. “Our estimates imply that with respect to college enrollment, a year of exposure to a disruptive male peer is equivalent to a 7 to 11 percent increase in class size for one year, a 2 percent reduction in Head Start participation, or a one-fourth standard deviation reduction in teacher quality.”

And that’s just exposure to one bad actor for one year. In some schools the earnest students are subjected to the disruption of multiple kids with disciplinary problems over many years.

Bacon’s bottom line: The researchers do not measure the impact of disruptive students directly. They use a proxy, children from households experiencing domestic violence, on the logic that there is a strong correlation between children experiencing or witnessing violence at home and their tendency to disrupt classrooms at school. It is not a perfect proxy, of course. Not all children from families experiencing domestic violence create disorder at school; likewise, some disruptive students come from non-violent families. The negative impact of students known to be disruptive arguably would be even stronger.

Acknowledging this impact does not tell us what to do about it. It does not tell us how to discipline or isolate disruptive students. But it does reinforce a point that I have made frequently on this blog: that disruptive pupils cause harm to pupils who come to school prepared to learn. If a teacher focuses his or her attention on the disruptive student, he spends less time teaching students who are behaving themselves. The effects are cumulative and long lasting, hurting academic performance, high school graduation rates, college attendance rates and future income.

The disciplinary issue has been politicized in recent years by American Civil Liberties Association and U.S. Justice Department insistence that school disciplinary action in Henrico County and other jurisdictions disproportionately affect minority students, especially blacks. Such a focus ignores the fact that the victims of disruptive behavior are also disproportionately minorities and blacks attending the same schools and classes.

The breakdown in school discipline has other effects not captured in this study. I chatted this weekend with a young woman who taught students at a Richmond-area middle school where there were a large number of disruptive students. She described to me how she went home after school and cried every day. Finally, she transferred to a new middle school in Henrico County where the students were well behaved. She is very happy with her job now. (Race and ethnicity never entered the discussion. Her problem was the behavior, not the racial identity, of the disruptive kids.) The well-known problem of teachers fleeing schools with disciplinary problems makes it more difficult for those institutions to recruit and retain good teachers, which arguably has a secondary negative impact on the motivated students.

I’m not saying that we should shunt all the disruptive kids off to reform school. But I am suggesting that we should be cognizant of the long-lasting impact of their behavior on other students. We cannot let their rights to a decent education be trumped by our concern for the troubled kids.