Henrico County has flipped from a majority-Republican to a majority-Democrat board of supervisors. That could be a good thing or a bad thing, depending. If Democrats nudge the county toward more rational, Smart Growth-like land use patterns — more infill, more density, more mixed use, more walkability — it could be a good thing. If they push the county into ill-thought-out spending initiatives, it could be a bad thing.

Based on the Richmond Times-Dispatch’s coverage of a two-day board retreat, it looks like spending will top the list. The three Democratic members of the board indicated their desire to expand the GRTC (Greater Richmond Transit Company) Route 19 to the Short Pump retail center at an estimated cost of $800,000 annually.

The purported benefit is greater access for job seekers. Tyrone E. Nelson, representing the Varina district at the east end of the county, said he could not understand why a county with a budget of nearly $1 billion had not yet devoted funds to bring bus service to the employment center. “I still don’t understand why it’s like pulling teeth to get public transportation to Short Pump. This is a 2018 need.”

His fellow Democrats expressed the same sentiment. “We’re not doing enough for job access,” said newly elected Courtney Lynch. “When you look at things we should spend money on, this should be something where we can get creative and get things done.”

Democrats and Republicans alike can agree that helping people gain access to jobs is a worthy goal. We want people to work so they can support themselves and their families. In Henrico County, the poorest residents tend to live in the far east end of the county, far from the affluent Short Pump commercial district where many jobs are available. GRTC already runs buses out Broad Street to Costco, and the expansion would extend the service a few miles more at seemingly modest cost.

That makes sense as a starting point for an inquiry: Hey, extending the bus line just a couple miles more would provide passengers access to a whole bunch of jobs they can’t reach now. Let’s take a closer look and see if it makes economic sense. From what I glean from the Times-Dispatch article and county documents, however, the supervisors skipped that let’s-see-if-it-makes-economic-sense step.

Henrico County Public Works has posted a slide presentation online covering proposed investments in roads, highways, sidewalks, bike trails, and mass transit. The slides contain a lot of information, but not everything that we, as citizens need to reach an informed conclusion. Perhaps the speaker making the slide presentation had more to say about the economics of bus service, but there is no indication of it in the Times-Dispatch article.

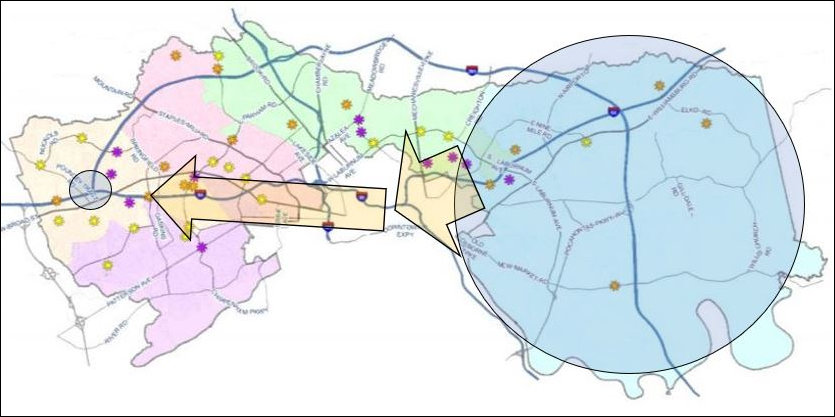

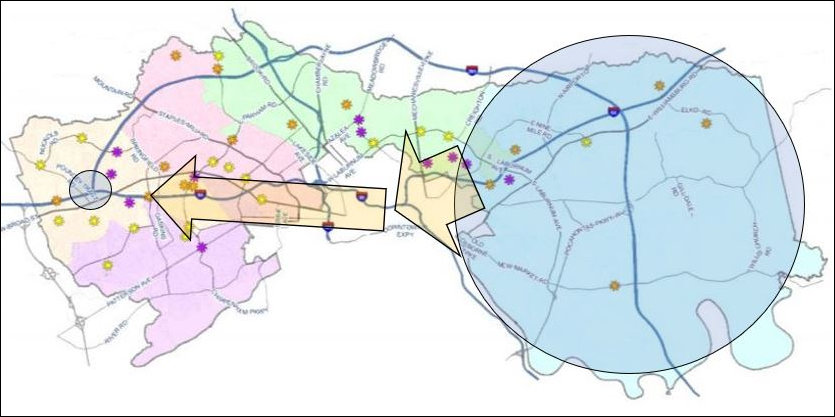

Let’s start with the map at atop this post. The big blue circle on the right is Mr. Nelson’s supervisor district. The small blue circle on the left is the Short Pump employment center. To get there, Nelson’s job-seeking constituents must take the bus into downtown Richmond where they would transfer to another bus running out to Short Pump.

The first question is how many passengers avail themselves of the bus service to access retail and service jobs along Broad Street at present? One hundred a day? A thousand? Ten thousand? Presumably, existing passenger loads would give us an order-of-magnitude idea of what might be expected if we extended the line. Alas, existing passenger numbers are not provided.

The more pertinent question is how many additional passengers are projected to avail themselves of the bus service going all the way to Short Pump. Again, in orders of magnitude, are we walking about 100 passengers, 1,000, or 10,000? This would seem to be a critical matter because, if the new service costs $800,000 a year to operate to benefit 100 passengers daily, we’re talking about an annual subsidy of $8,000 per passenger — an extraordinary sum. Why not just buy each passenger a new car? If we’re talking about benefiting 10,000 passengers, then the subsidy is only $80 per passenger, a nominal sum in which the social and tax benefits clearly outweigh the expenditure. If we’re talking about something in between, then the decision is not so clear.

As always, we should ask if there are alternative expenditures of money that would yield greater social benefits. Eight hundred thousand dollars is a nice chunk of change. I were a supervisor representing Nelson’s district, I would convene a meeting of GRTC, Uber, Lyft, Bridj, and other transportation-service companies and ask them, what kind of service could you provide my constituents for $800,000 worth of subsidies? Could you provide more point-to-point service providing more convenient schedules and shorter travel times, making it even easier to make the trip and find a job? Can you come up with a more imaginative solution than simply extending the existing bus schedule?

When such basic questions go unasked, we can be assured that money will be ill spent. Truly, Henrico has entered a new era — from one in which it made lousy land use decisions to one in which it will make lousy spending decisions.

City officials, notes the Post, say the ride-hailing services have benefited from Metro’s problems so it’s only fair that they be part of the solution.

City officials, notes the Post, say the ride-hailing services have benefited from Metro’s problems so it’s only fair that they be part of the solution. The Uber revolution keeps on churning. The transportation service company has finally rolled out a service in the Washington region that resembles the kind of ride-hailing jitney service that I long predicted eventually

The Uber revolution keeps on churning. The transportation service company has finally rolled out a service in the Washington region that resembles the kind of ride-hailing jitney service that I long predicted eventually

After LaHood report, more squabbling over Metro’s future. In the wake of recommendations by former Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, Virginia, Maryland and Washington, D.C., are edging toward compromises that would reform the ailing mass transit system’s governance system and shore up its financing. LaHood’s proposal to shrink the Metro board from six seats to five is drawing some bipartisan support, and legislation in Congress is being drafted, reports the

After LaHood report, more squabbling over Metro’s future. In the wake of recommendations by former Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, Virginia, Maryland and Washington, D.C., are edging toward compromises that would reform the ailing mass transit system’s governance system and shore up its financing. LaHood’s proposal to shrink the Metro board from six seats to five is drawing some bipartisan support, and legislation in Congress is being drafted, reports the  Washington Metro General Manager Paul J. Wiedefeld has been pushing for $15.5 billion in additional contributions from participating states and localities over the next 10 years, including $500 million in dedicated funding, to make the ailing commuter rail system safe and reliable.

Washington Metro General Manager Paul J. Wiedefeld has been pushing for $15.5 billion in additional contributions from participating states and localities over the next 10 years, including $500 million in dedicated funding, to make the ailing commuter rail system safe and reliable.