Del. Keith Hodges, R-Urbanna, discusses VDOT ditch and outfall issues with G.C. Morrow in 2013.

By Carol J. Bova

In the second part of this series, I described how the General Assembly recognized intrinsic problems in HB 1774, a bill designed to remedy deficiencies in stormwater legislation enacted in 2016 and scheduled to go into effect July 1 this year. But instead of killing the bill, legislators passed a substitute.

That substitute, HB 1774 H1, turned from implementation to study, directing the Commonwealth Center for Recurrent Flooding Resiliency to consider alternative methods of stormwater management in rural Tidewater localities.

By passing the substitute, the House and Senate delayed the effective date of the 2016 law and provided more time to work out problems that have come to light.

The Virginia Coastal Policy Center at William and Mary Law School will facilitate a work group for the HB 1774 study. This group will “include representatives from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Old Dominion University, the Virginia Department of Transportation, the Virginia Department of Environmental Quality, the Chesapeake Bay Commission, local governments, environmental interests, private mitigation providers, the agriculture industry, the engineering and development communities, and other stakeholders as determined necessary.”

It seems rural residents didn’t make the A-list for this group. That’s a shame because citizen groups have studied water drainage issues in low-lying areas near the Chesapeake Bay, and they learned a few things that the experts overlook. Even the HB 1774 substitute, which aims to fix problems in the original HB 1774… which in turn was supposed to fix the 2016 law… could turn out to be gravely flawed.

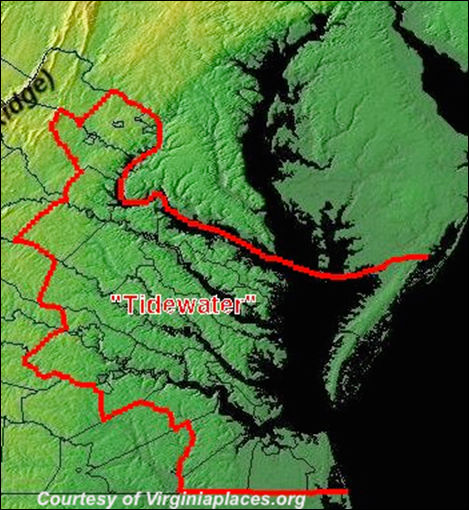

The revised HB 1774 changes the project area from six rural counties of the Middle Peninsula to the 29 counties and 17 cities of Virginia’s Tidewater. If the concept moves beyond the study stage, developers in ten urban counties — Arlington, Chesterfield, Fairfax, Hanover, Henrico, James City, Prince William, Spotsylvania, Stafford, and York — will be able to buy stormwater credits generated by the rural Tidewater counties similar to the way developers can offset the impact of their projects by purchasing credits from a wetlands bank.

The “Tidewater” localities are outlined in red.

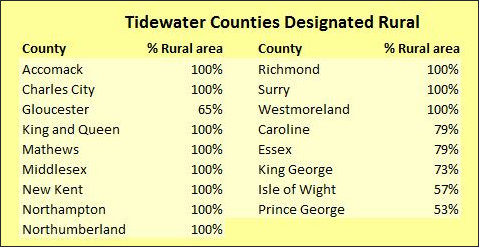

Nineteen counties have enough rural locations to establish Rural Development Growth areas along their state roads and highways if they agree to manage the new Regional Stormwater Best Practicies facilities (RSPs). In theory, these facilities will generate enough offset credits to let the RDGs use the current stormwater standards instead of the new, stricter standards, and still provide enough credits to sell to urban developers who need them. If the governor signs HB 2009, which passed the House and Senate, the localities could hire a third party to handle both the RSP management and credit sales on their behalf.

The original bill estimated the it would cost the Department of Environmental Quality $490,000 annually to hire staff to monitor the program for its first five years. But the bill provided no estimate of what expense localities would incur to administer the program, how much developers in urban counties might save, or how much income might be generated through the sale of credits. Presumably, the work group will address these issues.

Questions Raised by H.B. 1774

Will the work group recognize that water should not remain in VDOT’s roadside ditches long enough to be effectively treated?

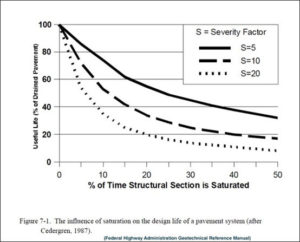

The more frequently roadbeds are saturated with water, the more quickly they deteriorate.

The ditches exist for two reasons. First, to convey water away from the roadbed to prevent deterioration. The Federal Highway Administration explained the connection in May 2006: “If the pavement system is saturated only 10% of its life (e.g., about one month per year), [it]…will be serviceable only about 50% of its fully drained performance period.” (The severity factor for 10% is shown as S=10 in the chart.)

Second, ditches exist to convey stream flow to a pipe under the road to reach its destination stream segment. Stream flow cannot be separated from stormwater in the ditches.

The maintenance of VDOT ditches is VDOT’s responsibility, not that of the localities. Working closely with Mathews County, VDOT has made progress recently through improved maintenance and joint revenue sharing projects to restore failed roadside drainage that has damaged landowners’ property and timberland.

Will the Center’s study encourage or derail those efforts? Let’s just say that VDOT will participate in the study group, and upper-echelon staff still don’t believe roadside ditches need to drain. As the Chief Deputy Commissioner of VDOT, Quintin D. Elliott, said on a Mathews ditch tour in 2013, “Stormwater standing in the ditches has no impact on roadbed integrity.”

VDOT’s stance supports the Middle Peninsula Planning District myth that seal-level rise, not maintenance shortcomings, causes road draininage failures,

Why assign the Commonwealth Center for Recurrent Flooding and Resiliency to study rural development and stormwater management when its mission statement points to helping localities build “resilience to rising waters, ” more commonly known as sea-level rise, unless the intent is to perpetuate that myth?

Continued in Part Four: H.B. 1774–What Is the Connection Between Recurrent Flooding and Flooded Roads?

Carol Bova is author of “Drowning a County: When urban myths destroy rural drainage,” a book documenting VDOT’s neglect of its highway drainage in Mathews County.