by James A. Bacon

According to a 2011 Wall Street Journal article, Aspen, Colo., could boast of having the most expensive real estate in the country. I don’t know if that’s still true, but I wouldn’t be surprised. As I sit here blogging at Ink! Coffee, looking upon a patio filled with Pellegrino umbrellas and baskets of bright mountain flowers while perusing the real estate ads in The Aspen Times, it quickly becomes clear that this is a place where I could never afford to live. A 3,414-square-foot home with a view of Aspen Mountain and within walking distance of downtown is on the market for $4,995,000. Select neighborhoods in Manhattan might be more expensive on a per-square-foot basis — I don’t pretend to know the national real estate market — but there cannot be many places that are.

Prone as I am to over-thinking absolutely everything, I have been asking myself, how did Aspen get to be one of the most desirable locations in the planet, while small mountain towns in Virginia with comparable natural beauty slide into senescence? Does Aspen provide lessons that Virginia communities can learn from — not with the unrealistic aim of becoming a playground of the one percent, but with the modest goal of attracting tourists and retirees, supporting jobs, lifting the tax base, and paying for amenities that make life more enjoyable for the people who live there?

In the article that follows, I will endeavor to address those questions, fully cognizant that anything I say is based upon the hasty and superficial impressions. My methodology is simple: I stroll around town with iPhone camera in hand and an eye to observing land use, architecture, transportation, and the retail scene. As always, I pay attention to the quality of the public sphere and the “small spaces.” When possible, I engage people in conversation. As it happens, Aspeners (or Aspenites, whatever they call themselves) are incredibly friendly and eager to talk about their fair city.

Aspen got its start in the late 1880s as a silver-mining boom town. When the silver boom went bust, so did the town. Fortunes did not revive until 1946 when Friedl Pfeifer, a former Austrian skiing champion, linked up with industrialist Walter Paepcke and his wife Elizabeth to form the Aspen Skiing Corporation. The town’s most enduring resource, as it turned out, was not silver but world-class skiing.

The inter-mountain west has many popular ski resorts, but none has done as well as Aspen at winning name recognition and attracting the super-rich. One key to its phenomenal success, I would suggest, is its silver-mining inheritance: a downtown laid out in a classic grid street pattern, a number of handsome brick buildings, and a municipal government intent upon preserving that heritage. Aspen has something that many of its ski-resort peers does not: walkability. Admittedly, Aspen isn’t the only walkable ski town — Jackson, Wyoming, springs to mind — so pedestrian ambiance is not exclusively responsible for vaulting it into the real estate stratosphere. But a comparison with Virginia/West Virginia ski resorts such as Wintergreen, Snowshoe and Massanutten lacking downtown districts suggest that walkability is a critical differentiator.

Downtown Aspen, comprising about two dozen blocks, is a destination in itself, and real estate ads tout houses’ proximity to the urban center. While the “Mountain Modern” style of architecture often presents a jarring contrast with the 1880s-era buildings, the overall effect is still magical. Visitors come to Aspen, fall in love, and gladly pay a premium to buy a house or condominium that allows them to live here.

Not only are historic buildings from Aspen’s silver-mining past architecturally distinctive but they help define the walkable street space.

Walkability

One of the first things my wife, friends and I noticed when strolling around downtown was the paucity of cars. Traffic was negligible. I assumed the empty streets reflected the lassitude of the summer season at a skiing destination. But a friendly acquaintance, a commodities trader who moved here from Chicago, assured me otherwise. We were, in fact, experiencing peak downtown traffic. Summer tourism is booming, and a lot of people bring their own cars and four-wheel drives to take advantage of the hiking, fishing, rock climbing, and whitewater rafting.

While cars may be scarce, human beings are everywhere. The ability to live here without driving is a prime attraction. People can meet most of their daily needs by walking and biking. The commodities trader said he goes a week at a time without ever stepping in a car. Another acquaintance, a native Philadelphian who lives here eight months of the year and does business in New York, said when he recently sold a Jeep he’d owned twelve years, it only had 15,000 miles on it.

Uncongested streets are the result of thoughtful design. Aspen hews to the rules of classical urbanism. For starters, the buildings define the street space. Rather than standing out and saying, “Hey, look at me” with egocentric starchitect designs, they conform with one another in size, height and relationship to the street. By abutting the sidewalks, their facades delineate the public space of the sidewalk realm. While you won’t see many cars driving around, plenty are using the on-street parking — and that’s a good thing. Parked cars and building facades bracket the pedestrian domain as a distinct space. This pedestrian realm, as I shall describe, is adorned by flower gardens, rain gardens, statuary, street seating, and window shopping that make it extraordinarily inviting.

The town promotes walkability in other ways. Street corners are sharp, not rounded, requiring cars to slow down when they turn and also making for shorter pedestrian transit across streets The city has no stoplights; cars are required to yield to pedestrians in crosswalks. By encouraging people to walk and bike places, the lack of stoplights creates a dynamic where people don’t drive …. and don’t need stoplights.

The community also has invested in bicycle racks and stands of free bicycles, buses (running on compressed natural gas, naturally) that link Aspen with other communities in Pitkin County, and a free circulator bus in downtown. By my casual observation, more people use bicycles than cars to get around. Indeed, skateboards and Segways are common modes of conveyance.

Parking policy is critical. I don’t know what official policy is, but I can see the results. I observed only two lots in downtown proper, and one of them served a grocery store. Most parking is relegated on on-street slots, alleyways and garages. Insofar as parking lots and parking decks clash with walkability, creating visual dead zones, Aspen city policy avoids a cardinal sin committed by all too many other municipalities.

Place Making

Crucial to making a a place walkable is sustaining visual interest. Perhaps the most effective eye candy is other people. If the people in question are young, svelte and dressed in Spandex, all the better. Here in Aspen, walkability feeds upon itself. One of the reasons people like walking places is to enjoy the pleasure of seeing and encountering other people.

Aspen residents also love flowers. Downtown is full of pocket gardens — no space goes unwasted. Colorful mountain flowers adorn every every odd patch of land between buildings. Aspenites hang flowers in baskets, line their window sills with them, and place them in giant urns.

People also love their statuary. The city doesn’t go in for the giant European-style monuments (although it has erected a modest statue of skiier Friedl Pfeifer), but there are numerous small statues on private plots of land, usually set amidst flower gardens. Aspenites, in my observation, favor of depictions of wildlife like the one above.

People also love their statuary. The city doesn’t go in for the giant European-style monuments (although it has erected a modest statue of skiier Friedl Pfeifer), but there are numerous small statues on private plots of land, usually set amidst flower gardens. Aspenites, in my observation, favor of depictions of wildlife like the one above.

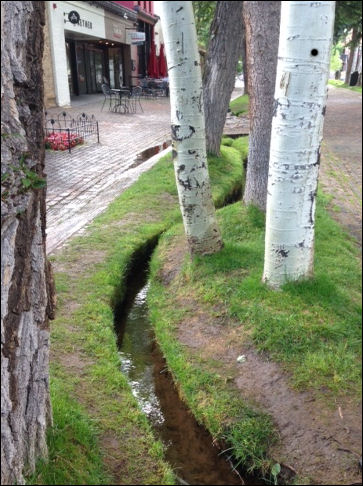

Over the years Aspen City Council has invested in creating plazas, parks and other attractive public places. Downtown can boast of an extraordinary one-block pedestrian mall (seen above) where people can sit under aspen trees, drink wine and eat meals served by restaurants on the mall. Perhaps the most remarkable touch was a tiny brook running through the middle of the mall. Any other municipality would have run the water through an underground pipe. Here, the stream created a unique feature that I have not seen in an urban garden anywhere else.

What does one call this body of water? A stream? A brook? A rivulet? Whatever, it is one of the most delightful sights I have ever beheld, and it epitomizes the extraordinary attention that the locals pay to small spaces. Above, the rivulet runs through a flower garden. To the left, it cuts through some aspen trees. If you need a sense of scale, the channel is just wide enough for a golden retriever to bask in. (We saw a dog cooling off later in the day. Just don’t drink from it, sparkling clear as the water appears. We saw another dog pee in it.)

Virtuous cycle

Aspen has not invested in any mega-projects that I can see. Instead, City Council has made small incremental improvements of a type that any Virginia city or town could afford — not all at once, of course, but over a generation or two.

The sustained effort has set into motion a highly virtuous cycle: Tourists come to ski and then fall in love with the city. They buy a house or condominium, driving up prices. Higher real estate valuations bring in higher tax revenues. In The Aspen Times I see a house selling for $7.8 million that brings in $17,500 a year in property tax revenues. When the average house is valued in multiples of millions of dollars, the tourism/second home/retirement nexus generates a gusher of tax revenue. Thus, City Council can afford to invest in more amenities — parks, trails, plazas, street ornamentation — that elevate the quality of life for everyone, the super-rich and locals alike.

This cycle may not seem so virtuous to local retail workers and bartenders who can’t afford to buy a house in Aspen near where they work. (Real estate is so expensive that I heard a story of a developer who purchased two vacant lots within walking distance of downtown for more than $10 million.) The working class does not live in Aspen — workers live in outlying communities, often riding buses into town. Although City Council has attempted to provide some affordable housing, I hear from locals, stiff density restrictions aggravate the housing scarcity. City policy preserves and protects the ambiance that the city’s 7,000 or so registered voters — and the city’s super-rich visitors — love so much. But in so doing, it perpetuates a transfer of wealth from the the renting class to the propertied class. Such are the inherent contradictions of progressive politics.

Can the cities and towns of Virginia’s mountainous west spark a similar virtuous cycle at a more modest level? Can they position themselves as locales where people come to play in an environment of extraordinary natural beauty — hiking, fishing, camping, spelunking, kayaking, rafting, rock climbing, mountain biking, ATV riding, bunji jumping, etc. — fall in love with the area, buy second homes and retirement homes, push up property values and invest in the amenities that benefit both locals and visitors alike?

The obvious difference between Aspen and Virginia towns such as Abingdon, Lexington and Staunton, or even resort communities like Wintergreen and the Homestead, is that Colorado has world-class skiing and Virginia does not. The Rockies rise higher, allowing longer ski slopes, and elevations are higher (Aspen is around 8,000 feet above sea level), creating consistently better snow conditions. That fact alone will make it impossible for any Virginia community to replicate Aspen.

But Virginia communities have a tremendous advantage: proximity to East Coast population centers. Aspen is remote. After flying to Denver at considerable expense, we had to rent a car and drive four hours to reach Aspen. Virginia communities as far south as Roanoke are located within a four-five hour drive of the Washington metropolitan area. Furthermore, Virginia communities are far more affordable. While Virginia communities don’t have much prospect of attracting the super-rich, they do have a shot at attracting the modestly rich and the well-to-do.

Aspen’s other hard-to-replicate asset is its downtown. Fortunately, many of Virginia’s mountain cities and towns were founded in an era when grid streets were the norm. Staunton, Lexington, Roanoke, Harrisonburg, Abingdon and Abingdon have charming downtowns. Sadly, local governments have cluttered and defiled outlying areas with small-town versions of “suburban sprawl” — scattered, disconnected, low-density growth that will take literally decades to un-do. But Aspen didn’t become Aspen overnight. Articulating a vision, building a consensus and sticking to it can repair the landscape and build upon existing assets like the Appalachian Trail, the Skyline Drive and the Virginia Creeper Trail.

Virginia also can draw upon rich historical, cultural and agricultural assets as well as Blue Ridge mountain landscapes that are just as beautiful, if not as spectacular, as the Rockies. Virginia communities also can bring to bear unique regional cuisine, musical traditions, mountain crafts and locally grown foods. The trick is to not view tourism as an economic generator by itself — the dollars are too small to support the economy — but as a means to create an enviable lifestyle and a tourism/second home/retirement complex that supports jobs, builds the tax base and supports a high quality of life.