by James A. Bacon

The proposed Atlantic Coast Pipeline (ACP) and Mountain Valley Pipeline (MVP), designed to bring low-price natural gas in the Marcellus and Utica shale fields to Virginia and North Carolina, pose significant risks to electric utility rate payers and landowners along their routes, argues a new study, “Risks Associated with Natural Gas Pipeline Expansion in Appalachia.”

“Pipelines out of the Marcellus and Utica region are being overbuilt,” states the report, written by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, whose stated mission is to accelerate the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. “Overbuilding puts ratepayers at risk of paying for excess capacity, landowners at risk of sacrificing property to unnecessary projects, and investors at risk of loss if shipping contracts are not renewed and pipelines are underused.”

A major justification for both pipelines is to provide Dominion Virginia Power and other electric utilities access to natural gas from West Virginia and Ohio, which for several years has been selling at a discount to Gulf of Mexico gas. But once a slew of proposed pipelines is built, the report contends, that price advantage likely will disappear, raising the possibility that the $9 billion cost of building the two pipelines will exceed the savings from lower gas prices.

“Shale drillers cannot continue to produce below cost indefinitely,” states the report. “In the longer term (10-15 years), it is likely that Marcellus and Utica gas prices will stabilize at a somewhat higher level. These longer-term prices will have a significant impact on the long-term economics of the Atlantic Coast Pipeline, which is designed as a 40-year project.”

Aaron Ruby, a spokesman for Dominion Transmission, managing partner of the ACP, disputed the conclusions of the report, saying, “There is no question about the urgent public need for the Atlantic Coast Pipeline. This project was developed in response to the real and demonstrated need of public utilities in Virginia and North Carolina. … Demand for natural gas in the region will increase nearly 165 percent from 2010 to 2013. Yet there is not enough infrastructure or supply … to meet this growing demand.”

Increased demand will come from electric utilities switching from coal to natural gas and from population growth, Ruby said. In Hampton Roads natural gas is in such short supply that service has been curtailed during extreme weather events for industrial customers, and attracting new customers burning natural gas is all but impossible.

Last month 33 area legislators signed a letter saying, “The need for this project is urgent; to put it bluntly, our region’s natural gas transportation system has reached a tipping point. The pipelines serving Hampton Roads are fully subscribed. Without new infrastructure, there is no way to meet our region’s rising demand for natural gas … crippling out prospects for economic growth.”

Mountain Valley Pipeline said that it had retained Wood Mackenzie Inc. to provide an independent analysis of long-term natural gas supply and demand in the Southeast. The resulting report, says MVP spokesperson Natalie Cox, “makes clear that the Southeast market alone has more than enough natural gas demand to support the MVP’s current capacity of 2.00 [decatherms] per day, and it’s important to remember that [the] Southeast is only one of MVP’s target markets.”

The Marcellus gas boom

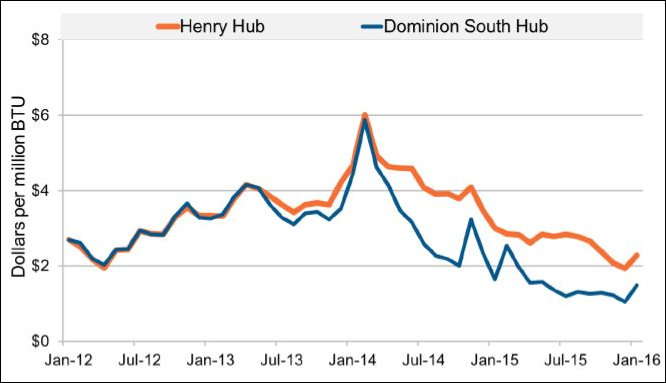

The pipeline-building boom has been driven by soaring natural gas production in the Marcellus and Utica shale fields, in which production has outpaced the ability of pipeline companies serving the region to transport the gas to customers. A persistent price disparity has opened up between the “Henry Hub” price for Gulf gas and the “Dominion South” hub for shale gas, as seen in the graph above. Backers of both the ACP and MVP projects have argued that their pipelines will allow electric utilities to access the lower-priced Marcellus gas, saving $377 million a year for ACP’s Virginia and North Carolina customers alone.

The low gas prices are driving a race among natural gas companies to build new pipeline capacity to reach higher-priced markets, states the IEEFA report. “Pipeline companies [are] competing to see who can build out the best networks the quickest.”

Energy holding companies with utilities have an interest in building new lines because regulatory structures allow pipelines to earn a higher return on capital than other categories of investment, the report contends. “If the regulated utility’s parent company can build its own pipeline for use by its regulated subsidiary, it can capture this profit, giving a utility holding company an incentive to prioritize building its own pipeline rather than utilizing that of another company. This structure also shifts some of the risk of pipeline development from the developer and its shareholders to the regulated utility’s ratepayers.”

Even players in the gas industry acknowledges that pipelines are likely to be overbuilt, the IEEFA report says, quoting Kelcy Warren, CEO of Energy Transfer Partners. “The pipeline business will overbuild until the end of time. I mean, that’s what competitive people do,” he said in an earnings call last year.

When pipelines are built unnecessarily, the report argues, landowners along the route are unnecessarily put at risk of having their land taken through eminent domain and potentially damaged, and communities along the routes may be at greater risk from gas explosions.

Gas pipelines lightly regulated

Natural gas transmission pipelines are regulated by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), which does not exercise the same level of oversight as state regulatory commissions, the report says. To ascertain public need for a proposed project, FERC relies upon whether a pipeline developer has been able to recruit enough companies to contract for capacity on the line. “If a pipeline is fully or near fully subscribed, FERC considers this strong evidence that the pipeline is necessary.”

Furthermore, the report notes, FERC sets “recourse” rates — the rate that a shipper is allowed to demand and receive — that allows a Return on Equity (ROE) of 14%, considerably higher than the ROE, typically around 10%, granted by state regulatory commissions. In theory, pipelines provide a more attractive investment return for holding companies like Dominion Resources than for state-regulated projects.

The “recourse” rates apply to only a small fraction of the gas that would flow through the ACP, however. Ninety-six percent of the capacity of that pipeline, says Dominion’s Ruby, would be locked up in negotiated 20-year contracts. The ROE embedded in those negotiated rates is not public information. The IEEFA report cited a National Gas Supply Association study that found that a majority of the 32 natural gas pipeline companies studied generated ROE closer to 12%.

The main role state regulatory commission has in regulating interstate natural gas pipelines is approving the pass-through of pipeline costs to customers. In Virginia, the State Corporation Commission must conclude that the cost has been prudently incurred. While the SCC could in theory reduce the pass-through incurred by Dominion Virginia Power for the ACP’s rates, that decision would not occur until after a pipeline has already been constructed, the IEEFA report says, which gives the commission no power to curtail overbuilding.

“Rates charged for shipping gas on pipelines are ultimately passed through to the consumer of the gas, largely customers of electric and natural gas utilities,” states the report. “That leaves ratepayers at risk of paying for unnecessary new capacity.”

Public need questioned

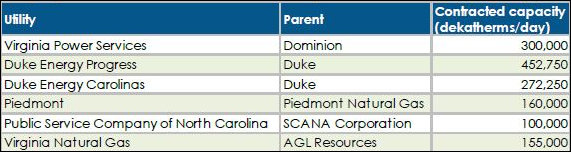

ACP is a joint venture of Dominion Resources (which has a 45% interest), Duke Energy (4o%), Piedmont Natural Gas Company (10%), and AGL Resources (5%). The pipeline’s owners and customers are almost synonymous. The pipeline partners account for 74% of the 1,439 dekatherms per day of contracted capacity. In other words, three-quarters of the multibillion-dollar pipeline cost will be charged to rate payers of the utilities that, through their parent companies, own the pipeline.

While the pipeline companies generate a potentially higher return on capital, the rate payers get stuck with much of the risk, the IEEFA report contends. A big risk is that the $5 billion cost of building the pipeline will exceed the savings from cheaper natural gas.

ACP’s claims of savings for rate payers are based upon an ICF International study that asserted that Marcellus/Utica gas would continue to be $1 to $1.75 per million BTU cheaper than Gulf gas through 2034, saving Virginia and North Carolina rate payers $377 million per year, says IEEFA. But that finding contradicts current market expectations.

As more pipelines are built out of the Marcellus and Utica region, the excess pipeline capacity will further narrow the price differential between the hubs. That is, as natural gas pipeline capacity increases to meet or exceed the glut of natural gas supply, natural gas prices in the Marcellus should rise.

Dominion’s Aaron responds that ACP’s contracts lock in gas prices for 20 years. If the gap between Marcellus and Gulf Coast gas prices does narrow, there won’t be any impact for two decades. And even then, Dominion, Duke and the others will benefit from more diversified sources of supply that would insulate themselves from events that create price spikes, such as Hurricane Katrina’s disruption to the Gulf gas industry.

Recommendations

IEEFA urges a “comprehensive planning process” for natural gas pipelines that could reduce overbuilding and dampen returns on pipeline development. The high returns on equity embedded in recourse rates “is especially egregious given that the growing trend of transactions between regulated utilities and affiliated pipeline developers tends to shift risk from utility shareholders to ratepayers.”

Also, Virginia’s State Corporation Commission should “closely examine the prudence of contracts signed by regulated utilities to ship gas on a pipeline owned by affiliated companies.”

Finally, FERC should suspend evaluation of the ACP and MVP pipelines until an “appropriate regional planning process” can be developed.

Conclude the authors: “Without a coordinated approach to natural gas pipeline planning, as exists for many other types of infrastructure, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission cannot make an honest determination of the need for these pipelines. Ratepayers and communities will shoulder much of the costs and risks … investments of nearly $9 billion that are poised for approval without adequate scrutiny.”