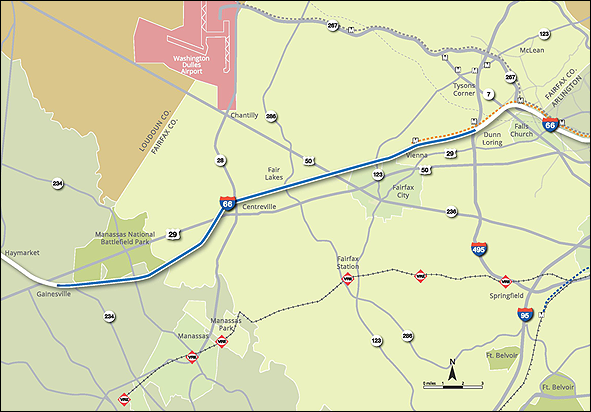

Location of the Transform 66 outside-the-beltway project. Map credit: Virginia Department of Transportation

Transportation Secretary Aubrey Layne makes a strong case that Virginia’s overhaul of the public-private partnership law made possible $2.5 billion in savings on Interstate 66.

On Nov. 3, Governor Terry McAuliffe made the audacious claim that his administration had saved taxpayers $2.5 billion on the Interstate 66-outside-the-Beltway project thanks to 2015 reforms to the Public-Private Partnership (P3) law.

The original proposal brought to Commonwealth by the former Office of Transportation Public-Private Partnerships indicated that the state would have to subsidize the construction of 25 miles of general-purpose lanes and express lanes by between $900 million and $1 billion — and the concessionaire would contribute nothing toward bus mass transit or future corridor improvements.

By the end of a revised, 16-month procurement process, the state struck a 50-year deal with a consortium of Cintra, Meridiam, Ferrovial Agroman US and Allan Myers VA, Inc. Express Mobility Partners agreed to pay Virginia $500 million up front, invest $800 million towards transit operations, and make $350 million in future corridor upgrades.

The I-66 corridor improvements, both inside the Beltway and out, are the signature transportation projects of the McAuliffe administration. After cleaning up the fallout from the Norfolk-Portsmouth Midtown-Downtown Tunnel project and the botched U.S. 460 Connector, the heat was on Transportation Secretary Aubrey Layne, to get I-66 right. While aspects of the inside- and outside-the-Beltway projects have been controversial, Layne can reasonably say one thing: He has saved the state $2.5 billion.

P3 projects have not always worked out well in Virginia, as Layne knows better than anyone. I wondered how it was possible to negotiate a deal that, on the surface at least, was so vastly superior to what the state had been considering. I sat down recently with Layne and Deputy Transportation Secretary Nick Donohue to get their story.

The starting point for understanding the McAuliffe administration’s approach to P3s is the continuum of risk associated with highway mega-projects. One approach, as the Virginia Department of Transportation (VDOT) did for decades, is to assume the risk for everything: cost overruns, construction delays, operations & maintenance, and the risk of financing, in particular, that toll revenues will suffice to pay bond obligations.

During the previous administration’s flirtation with P3s, an infatuation with concept of “privatization” inspired the state to dish off all the risk to the private sector. (Layne, a Republican, rarely mentions the McDonnell administration by name.) But Layne found that no more acceptable than keeping a project in-house with VDOT regardless of cost. Instead, Layne started with no preconceptions about the best way to structure a deal. Getting the best deal depended upon the situation, knowing the risks the state was comfortable assuming, and knowing the risks it was comfortable dishing off.

Back to the drawing board. Early in the administration, in 2014, the old P3 office delivered a proposal for I-66 for submission to the Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) for approval. “The P3 office had no idea what it was doing,” says Layne. “It was embarrassing.”

At the risk of delaying a high-priority project, Layne spiked the deal. He didn’t present it to the CTB. Rather, he waited for the General Assembly to enact major reforms to the P3 process so he could start over. The problem with the old process, he says, was that after soliciting proposals, VDOT selected one private consortium to negotiate with. Under the guise of protecting the partner’s proprietary information, VDOT conducted the negotiations out of the public eye. When a product emerged, the CTB had no choice but to vote it up or down without amendment. “I don’t know how anyone could have set up the process to be more biased,” says Layne.

Before soliciting private-sector proposals, Layne determined the essential elements from a public policy perspective the project needed to have. In other P3s, the state allowed the private party to chip away at public-interest protections, refusing to fund public transit in the transportation corridor, for instance, or penalizing the state for investing in projects that might drain traffic from toll revenues.

Layne next drew up a term sheet based on the “must have” attributes, and then asked VDOT to determine how much it would cost to deliver the project in-house. Just taking this obvious step would have saved $1.5 billion. The 2015 “public option” cost roughly $500 million less than the previous private sector proposal, thanks in large measure to the state’s ability to tap tax-free public financing, plus VDOT would put $800 million into transit and $350 million into future corridor improvements.

The in-house scenario established a baseline against which future proposals would be compared. Mass transit and park-n-ride were non-negotiable. If potential partners couldn’t deliver, Layne was fine with turning the I-66 project over to VDOT.

The P3 industry was unhappy with Virginia, and Layne says there was pushback in the General Assembly. (Transurban, one of the players, made $150,000 in campaign contributions 2014-2015.) “They said we were against P3s, we were killing the process, we were making numbers up,” Layne recalls. In truth, he says, they were upset that Virginia’s new approach would narrow their profit margins.

The virtues of competition. After soliciting potential partners, the state began talking to five teams. Talking to different players gave Layne keener insight into the economics of the deal. It quickly became apparent that, given the extraordinary revenue potential from tolls, some bidders were willing to pay the state in order to get the concession.

“The more people you talk to, the better the price discovery,” Layne says. “It was fascinating, the stuff we learned when we put it out to competition.”

For example, two teams asked if the commonwealth would allow commercial trucks to use the express lanes, generating more revenue than originally contemplated. VDOT hadn’t considered that possibility, but it enhanced the public benefit, so Layne agreed to it.

In the end, Express Mobility Partners made the best offer. The consortium gave Virginia everything the McAuliffe administration wanted — and invested in $1.5 billion in equity financing. That was a bigger equity investment than for all other P3 deals in the Commonwealth (including the Pocahontas Parkway, the 495 Express Lanes, the Midtown-Downtown Tunnel, U.S. 460, and the 95 Express Lanes) combined. A bigger equity stake means the private party has more skin in the game and has less debt exposure if revenue projections don’t pan out.

Crucial to the successful negotiation, says Layne, was McAuliffe’s attitude that he would rather have no deal than a bad deal. As long as VDOT could deliver the public option, the administration was able to walk away from a bad deal. McAuliffe’s approach contrasted to that of his predecessor. By publicly proclaiming U.S. 460 to be his top transportation priority, Gov. Bob McDonnell put enormous pressure on Layne’s predecessor, Sean Connaughton, to keep the project moving, even if the cost and risk were unacceptable.

“The governor wasn’t up there saying, ‘I’ve got to have this deal,'” says Layne. “He’s never done anything but ask us to get the best deal.”