by James A. Bacon

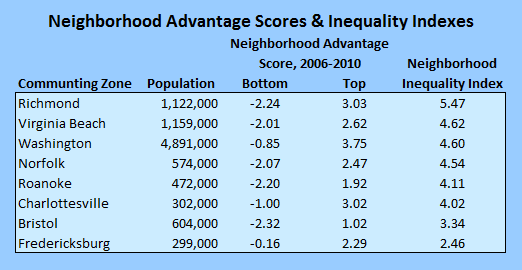

Neighborhoods in the Richmond metropolitan area are the most segregated by wealth and income in Virginia and the third most segregated of any region in the United States, according to data crunched by Urban Institute fellow Rolf Pendall. By the same token (assuming I read the fine print in tabular form correctly), Fredericksburg is the least segregated by wealth and income of any region in Virginia and the country.

As the income gap widens in the United States, so does the gap between the most affluent and the poorest neighborhoods, contends Pendall in a new report, “Worlds Apart: Inequality in America’s Most and Least Affluent Neighborhoods.” This polarization has occurred despite the urban revival of many U.S. metros.

“Though not as far apart in space from the bottom neighborhoods as affluent suburban and exurban enclaves,” writes Pendall, “top neighborhoods in central cities still are separate worlds from those of the nation’s lowest-income residents. And even the modest physical distance between top and bottom neighborhoods is often interrupted by physical barriers like Washington’s Anacostia River, the San Francisco Bay, and Interstate 35 in Austin.”

Instead of preserving islands of privilege, he argues, public policy should encourage the creation of mixed-income neighborhoods and districts in central cities and suburbs and invest more heavily the nation’s poorer neighborhoods.

One could argue with Pendall’s policy prescriptions — what should we do — but his description of the facts on the ground — what is — seems pretty straightforward. Insofar as most of us would like to see more equality of opportunity in our society, and insofar as an individual’s opportunities are shaped by his or her neighborhood environment, it is discouraging to see such wide disparities in the Richmond region where I live.

(If I were like some participants in this blog, I would go, “Oh, Urban Institute, that’s a liberal think tank, therefore it’s biased, therefore, I can disengage my brain and discount anything it says. But I try not to work that way. Pendall’s methodology seems perfectly reasonable, and if there are uncomfortable realities that must be grappled with, I will grapple with them.)

A couple of observations about the Virginia data. First, the Washington region (or, more precisely, commuting zone) has the strongest concentrations of wealth of any of the metros, even more than Richmond. But the poverty in its least advantaged neighborhoods appears to be more diluted, while in Richmond poverty is more concentrated.

Second, Fredericksburg seems notable for the notable lack of concentrated poverty. I can confirm this with some anecdotal evidence. My mother lives on Caroline Street, one of the more desirable streets in Fredericksburg’s historic district — but she is only two blocks from a housing project. As Pendall observes, smaller regions tend to have less inequality between neighborhoods, and Fredericksburg is one of the smallest regions covered in his survey.

What to do about it. To a carpenter, as the old saying goes, every problem looks like nail. Urban planners are prone to looking for urban planning solutions to the problems they observe. But solving the problem of extremes in wealth and poverty cannot readily be accomplished simply by mixing poor people and affluent people together. One of the advantages of being affluent is that it affords one the opportunity to separate oneself from crime, poor schools, disorderly conduct. In my observation, even liberal rich people like to live in neighborhoods that are safe and don’t have trash on the street. Politically, it will be difficult to compel the rich, powerful and well connected to do something they don’t want to do. It’s a zero-sum game.

To my mind, the better way to address the inequality of neighborhoods is to address the inequality of the residents within the neighborhoods. One way to do that is to scrap a monetary policy that rewards the wealthy (holders of stocks and bonds) and punishes small savers (whose financial assets reside in bank accounts and CDs). Another way to address income inequality is to embrace a tax and regulatory regime that encourages economic growth, which encourages job creation, which, when the labor market tightens enough, promotes income growth for wage earners.

Bacon’s bottom line: The phenomenon Pendall describes is real. But the policy prescription at which he hints addresses the surface of the problem, not the underlying cause.