by James A. Bacon

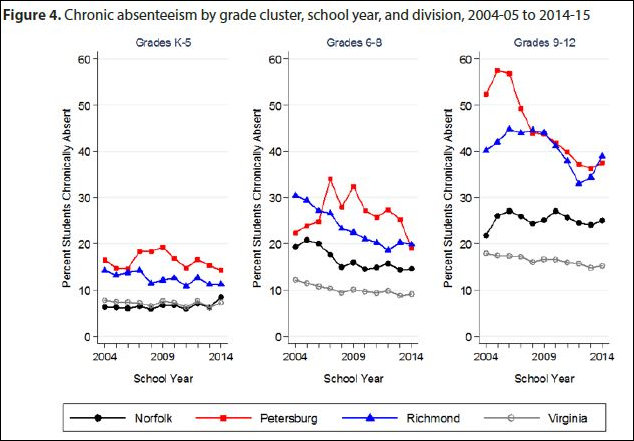

Slightly more than one in ten Virginia school students were “chronically absent” from school in the 2014-2015 school year, meaning that they missed 10%, or 18 out of 180 days, or more of the school year, according to a new study published by Luke C. Miller and Amanda Johnson for the University of Virginia EdPolicy Works.

Nor surprisingly, the authors found that chronic absenteeism was associated with lower standardized test scores and a higher propensity to drop out of school. Hardly shocking, they found that low-income and minority students were more likely to be absent. The study, “Chronic Absenteeism in Virginia and the Challenged School Divisions,” focused on three troubled, inner-city school systems, Norfolk, Richmond, and Petersburg, where absenteeism is far more prevalent than for Virginia schools as a whole.

The primary contribution of the study is to delve into possible causes of school absenteeism, with the idea that a keener understanding of the phenomenon will help us craft better solutions. Here is the authors’ framework for addressing the issue:

Reasons for being absent can be clustered into three categories. … First, students may not be able to attend school because they cannot attend, for example, if they are sick, they are homeless or experiencing other forms of housing instability, or they have family obligations such as caring for younger siblings. Second, some students are absent because they have an aversion to going to school, for example, if they are having a tough time adjusting to a new school or if they do not feel safe at school. Third, students are absent from school because either the students or the parents would rather the student be somewhere else, for example, hanging out with friends at the beach or going on a family vacation. By targeting one or more of these reasons, interventions have proven successful at reducing chronic absenteeism.

Miller and Johnson tested their proposition that unsafe schools might be a factor by correlating absenteeism with school-level measures of discipline, crime, and violence data. The correlation is not a strong one. “The relationship between school safety and chronic absenteeism is not consistent across the three school divisions or Virginia,” they write. “In Petersburg, the safest schools have the highest rates of absenteeism.”

The authors also examine the idea that students attending new schools might have a more difficult time adjusting, thus making them more prone to absenteeism. There the data seems more consistent. “Transitioning students are roughly 60% more likely than non-transitioning students to be chronically absent in Norfolk and Richmond and 50% more likely in Petersburg.”

The authors call for more research to focus on schools and school divisions with high concentrations of high-poverty students that have done a better job of reducing absenteeism and identifying the practices they employ.

Bacon’s bottom line: Translating the study’s findings on “transitioning students” into plain English, it seems entirely plausible that new kids in school, especially middle and high school, have a tougher time fitting in. Social cliques are already established, and it takes greater effort to find acceptance. Some kids may get discouraged, and they may skip school more frequently as a result. This phenomenon may be more pronounced in schools dominated by lower-income kids less indoctrinated in the middle-class mores of “put yourself in their shoes,” and “be nice to everyone.” Sadly, schools are powerless to address the reasons why low-income households, which are vulnerable to housing evictions, move to new districts in the middle of the school year.

Ferris Bueller — not your garden-variety chronically absent student.

On the other hand, some of the analysis seems ludicrous, such as the idea that students who chronically skip school might be “hanging out with friends at the beach” or “going on a family vacation.” Really? How many low-income households send their kids on spring beach week or take family vacations together? Ferris Bueller wannabes are not the problem.

The most muddled thinking involves the relationship between absenteeism and school safety. The only hypothesis considered in the study is that students might be more likely to skip school if they do not feel safe at school. That idea is plausible to the extent that some students who fear bullying might wish to avoid their tormentors. But it is just as likely that the students most inclined to inflict violence upon others tend to be the same students who are chronically absent. As the authors themselves acknowledge, the absentee numbers include time absent due to suspensions. Why do students get suspended — usually because they have gotten into fights or otherwise behaved violently.

Which gets us to a related matter. It’s not the absenteeism itself that causes students to do poorly in their studies, although missing class certainly doesn’t help matters. The kids who skip school are also the ones most likely to act up in class, disrupting the teaching of everyone. The authors themselves observe, “There is also evidence that having chronically absent classmates lowers the achievement of students who are not chronically absent themselves.” But somehow Miler and Johnson overlook the common-sense observation that the problem doesn’t arise from the troublesome students being absent, it arises from them being present — and disrupting class! Needless to say, these troubled students have other issues — disabilities, bad attitudes, whatever — that make them less motivated to succeed academically.

Finally, I find it astonishing that academic researchers could ignore the role of what some call the “lure of the street.” Some school kids just find school boring. They’d rather be where the action is, and in the inner-city school systems examined here, the action is associated with the street culture of sex, drugs and partying — basically, the same activities that many affluent kids engage in, with the difference that affluent kids are raised in households where they are expected to get grades good enough to gain them admission into college.

In the final analysis, the study was marginally useful in moving the debate over absenteeism in a useful direction… but only marginally.

(Hat tip: John Butcher.)

Upadate: Here is Butcher’s take on the absenteeism data.