by James A. Bacon

A new report by the Pew Research Center, “The Geography of America’s Shrinking Middle Class,” has garnered widespread attention by focusing on the erosion of America’s “middle class” between 2000 and 2014, confirming the dominant narrative of increasing income inequality across the United States. As a summary of the report emphasizes, “The middle class lost ground in nearly nine-in-ten U.S. metropolitan areas examined.”

The percentile share of the middle class fell in 203 of the 229 metropolitan statistical areas examined in the analysis. Meanwhile, the share of adults in upper-income households increased in 172 regions and the share in lower-income households increased in 160 regions over the same 14-year period.

The decline of the middle class is a reflection of rising income inequality in the U.S. Generally speaking, middle-class households are more prevalent in metropolitan areas where there is less of a gap between the incomes of households near the top and the bottom ends of the income distribution. Moreover, from 2000 to 2014, the middle-class share decreased more in areas with a greater increase in income inequality.

The study neglects to tell us how the shrinking middle class is faring nationally according to its methodology, or whether it is due primarily to upward or downward mobility. The trends vary widely from region to region, reflecting the circumstances of local economies. Manufacturing-oriented regions fared poorly, while energy-related economies prospered. At the same time, some regions are doing a better job of building their technology and professional-services sectors. If, as a generality, larger metros are making progress while smaller metros are sliding, that’s unfortunate for the smaller metros but it’s not necessarily a national crisis — it simply reflects the reality that competitive economic advantage is shifting from smaller to larger metros. It is a basic question but Pew ignores it.

While there is much to be said in favor of a strong middle class, a shrinking middle class (defined by Pew as between about $42,000 to $125,000 per year for a family of three) can be construed as a good thing if people are rising into the so-called upper-income class. The trend is clearly undesirable if it results from households sinking into the lower-income brackets. What appears to be happening is a little of both — although in Virginia upward mobility predominates.

Pew’s analysis covered five metropolitan regions in Virginia: Washington, Hampton Roads, Richmond, Lynchburg and Blacksburg. (Don’t ask me why Roanoke, Charlottesville and other smaller metros weren’t included, I don’t know.)

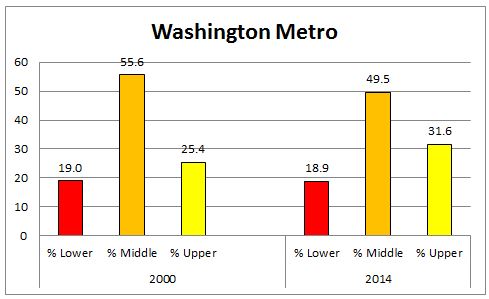

The Washington metro (see chart above) experienced what could be construed as an alarming decline in the middle class — 6.1 percentage points. But even a cursory look at the data shows that the lower-income group remained stable (actually declining 0.1%) while the upper-income group shot up. By Pew’s measure, the Washington region became more unequal. But it apparently did so by hundreds of thousands of households moving into higher income brackets. Is this “losing ground?” Are we supposed to flagellate ourselves over this?

Admittedly, Washington may be an outlier. It is, after all, America’s imperial city and, with the exception of occasional bouts of sequestration or defense cutbacks, it is largely immune from the trends that afflict other parts of the country. So, let’s take a look at Virginia’s second largest metropolitan area, Hampton Roads (labeled Virginia Beach).

Once again, the middle class shrunk. Oh, noooo! But look closer. So did the lower-income class. The affluent class increased by 4.8 percentage points. It is hard to spin this as anything but a positive development.

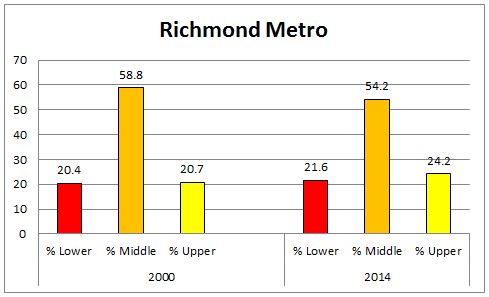

The outlook for the other three Virginia metros is less clear cut. Here’s Richmond:

The lower-income group increased by 1.2 percentage points, while the upper-income group increased by 3.5 percentage points. So, the Richmond region did experience an increase in income inequality during this period. Yet the “decline” of the middle was caused mainly by upward mobility. The increase in upper income was three times that of the increase in lower income. In an ideal world, there would be zero increase in the percentage of poor people. But this is hardly the picture of a region in the throes of a socio-economic crisis.

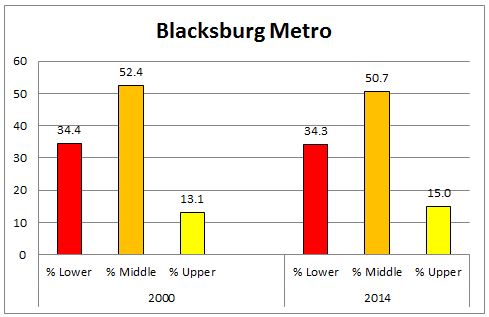

Here is the Blacksburg region:

Once again, we have a shrinking middle class (as defined by Pew). Yet the percentage of poor actually remained stable, shrinking by 0.1 points, while the percentage of upper-income households increased by 1.9 points. To my mind, these numbers paint a positive picture of what is occurring in the Blacksburg-area economy.

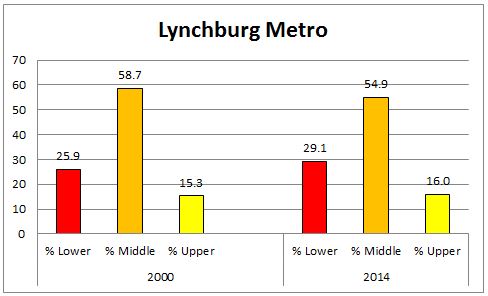

Finally, we have Lynchburg, the one metro of the five Virginia metros that seems to be struggling.

The percentage of lower-income households increased by 3.2 points, while the percentage of upper-income households rose only 0.7 points. The picture here is of more downward mobility than upward mobility in a small, manufacturing-oriented region struggling to maintain its economic competitiveness in the knowledge economy.

Virginia’s metropolitan regions may or may not be representative of the U.S. a whole (although in terms of income, age and wealth distribution Virginia comes closer to matching the national demographic profile than all but three other states). But the picture hardly looks dire. If the “middle class” is shrinking because so many people are moving into upper-income brackets, that’s a good thing, not a bad thing. That’s not to say we abandon efforts to create more opportunity for lower-income Americans — to the contrary, that goal is as pressing as ever — but a look at the Virginia data undercuts the notion that we are becoming a state of haves and have-nots. To the contrary, we made incremental progress toward a state of “haves.”