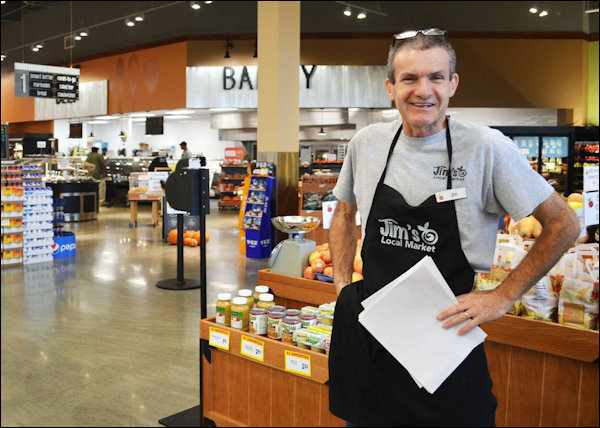

Inspired by a desire to wipe out food deserts, Jim Scanlon opened this Newport News store. Photo credit: Richmond Times-Dispatch.

The Richmond Times-Dispatch ran a profile today of Jim Scanlon, a former Ukrops Super Market executive who opened a grocery store near downtown Newport News and plans another in Richmond’s East End. His mission is to eliminate Virginia’s so-called “food deserts” one neighborhood at a time. The story of how Scanlon has worked with local economic development authorities in Newport News and with the backing of philanthropist Steven Markel in Richmond creates a message of hope.

But one must ask, how will Scanlon succeed where others have failed? As the article notes, the Brooks Crossing area of Newport News, where one of Scanlon’s stores is located, had been served by an unnamed grocery store until about two years ago, when it abruptly closed. Likewise, the East End of Richmond had been served by Community Pride, which shut down in 2004 after its African-American owner-entrepreneur, Johnny Johnson, encountered major financial difficulties.

I’ve read dozens of articles about food deserts and the effort to coax grocery stores into those areas. Reporters frequently describe how the old grocery stores closed but never seem curious about why. It’s not as if their customers suddenly became penniless. Poor people get food stamps to supplement their other sources of income just the way they always have. Social critics have argued that food stamps don’t provide enough money for a nutritious diet, and perhaps that’s true, but it’s not as if food stamps were ever sufficient by themselves to support a healthy diet.

Grocery stores in poor urban areas encounter problems that stores in affluent suburban areas do not. Urban stores have a higher incidents of theft and pilferage. They also have more “slip and slide” insurance claims, as I learned from Johnson. Before expanding too aggressively and getting overextended financially, Johnson was successful because, as an African American, he had a keen understanding of the markets he was serving. He knew how to hire reliable employees. He dispatched to pick up little old ladies who couldn’t drive to his stores. The demise of his business was a tragedy for many.

Ironically, while grocery stores have failed in poor urban neighborhoods, convenience stores have flourished. In Richmond’s East End, these stores are typically owned by Koreans, Middle Easterners or other ethnic minorities not bound to conventional white, professional-class thinking. Invariably, these are small, family businesses. The owner-shopkeepers work long hours, drafting spouses, children, cousins and other relatives as employees they can trust, and I would wager they accept smaller profit margins. They develop personal relationships with their customers, often extending small sums of store credit in a way that a conventional grocery store never would. Perhaps most important, convenience stores stock what their customers are buying, which, unfortunately, is heavy on junk food and cheap sources of carbohydrates like rice and pasta.

Food products that sell in middle-class neighborhoods don’t sell as well in the inner city, where poor people don’t have the same tastes, don’t have the same disposable income, and make different trade-offs between cost and quality. Grocery-store business models built around catering to the middle class don’t work in the ‘hood unless the demographics are shifting — which happens to be the case in Richmond’s Church Hill area and is likely so in Newport News’ Brooks Crossing redevelopment as well. If Scanlon’s ventures pay off, I expect the credit to go to middle-class gentrifiers.

What worries me is that, as we see in efforts to ameliorate the housing and transportation issues of the poor, fixing the food-desert problem deals with a symptom of poverty without addressing the underlying causes. What poor people really need first are stable jobs and higher incomes so they can afford to buy better food. Then they need to cultivate a taste for healthier cuisine. Otherwise, they’ll end up like a lot of better-off Americans, using their money to buy more expensive junk food.