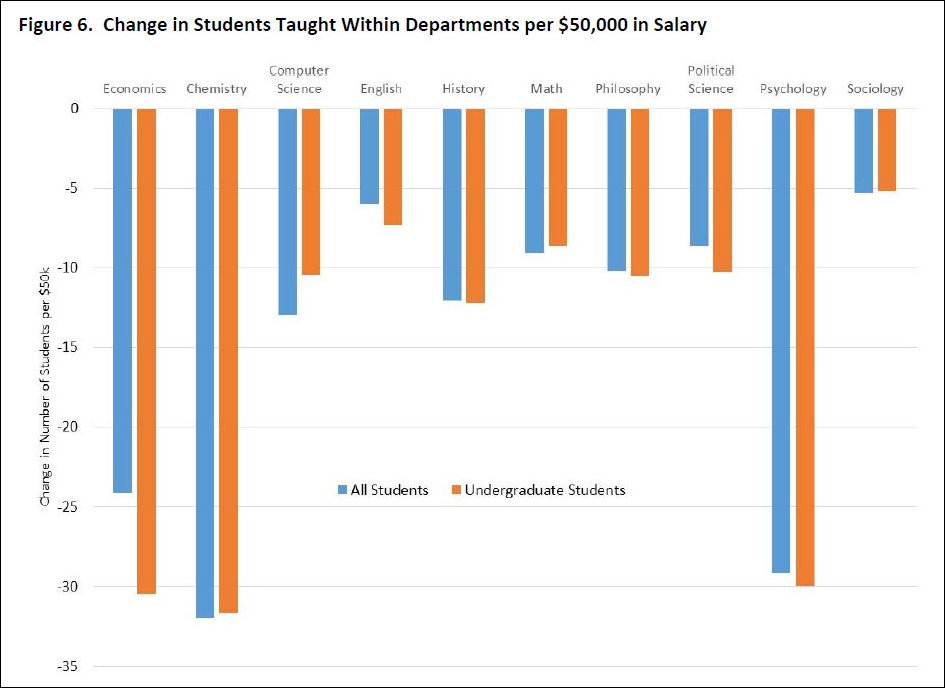

Faculty productivity paradox: The more professors are paid at UVa and the University of Michigan, the less they teach. Source: “Faculty Deployment in Research Universities. (“Click for larger image.)

Newly published research by Sarah Turner at the University of Virginia and Paul N. Courant at the University of Michigan sheds light on a critical factor driving the cost of attendance at public universities: faculty productivity.

Turner’s and Courant’s findings buttress a point we have made repeatedly on this blog: that higher-paid faculty members spend more time on research and teach fewer students than lesser-paid faculty members. Depending upon the academic department, a $50,000 increase in salary results in 5% to 30% fewer students taught (as seen in the chart above).

The analysis is restricted to tenure-track faculty. It does not compare the teaching loads to non-tenure-track “instructors” who get paid less and take on even heavier teaching loads than the professors.

Sarah E. Turner

In a paper recently published by the National Bureau of Economic Research, “Faculty Deployment in Research Universities,” Turner and Courant ask if faculty members are deployed efficiently at research universities. They base their findings on an in-depth analysis of the University of Michigan and the University of Virginia, which are consistently ranked among the top public research universities in the country.

The authors conclude that UVa and Michigan are indeed “efficient” in the sense that they are economically rational in allocating faculty time and effort.

Tenure track faculty in research universities teach and they do research. Over the past several decades, the relative prices — in terms of wages paid to faculty — of those two activities have changed markedly. The price of research has gone up way more than the price of teaching. Salaries have risen more more in elite research institutions than in universities generally. …

Departments in research universities … must pay high salaries in order to employ research-productive faculty. These faculty, in turn, contribute most to the universities’ goals (which include teaching as well as research) by following their comparative advantage and teaching less, and also in teaching in ways that are complementary with research — notably graduate courses. The university pays these faculty well because they are especially good at research. It makes perfect sense that they would also have relatively low teaching loads (along with relatively higher research expectations) …

If we accept that the value placed on research in elite research universit[ies] is warranted, we conclude that the deployment of faculty is generally consistent with rational behavior on the part of those universities. Faculty salaries vary, for a variety of reasons, and the universities respond to that variation by economizing on the most expensive faculty….

Bacon’s bottom line. Note the caveat above: “If we accept that the value placed on research at elite research universities is warranted…” This goes to the heart of the debate over college affordability. UVa and other Virginia universities place an extremely high value on research. Why? Because the publication of research has an outsized effect on a university’s prestige, and the research dollars brought in enables departments to employ more faculty and graduate students, also markers of departmental prestige. By contrast, the cost of attendance is incidental to departmental interests.

Students and parents have a different perspective. While an institution’s prestige is clearly a factor in deciding where to attend college, the cost of attendance typically is a central concern as well.

In sum, universities can emphasize faculty productivity in research or in teaching. As the Turner/Courant data confirms, the system pays the most to the faculty members who teach the least. While the authors don’t go the extra step and say so, it seems clear to anyone outside of academe that undergraduate students are paying ever-higher tuition for the privilege of being taught increasingly by junior professors and instructors so tenured faculty can spend more time on writing and research.