Despite a growing population in its watershed, the Chesapeake Bay continued its long, slow recovery in 2012, reports the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CFB). It may be another four decades before we can say that we “saved” the Bay, but we’re moving in the right direction.

Five of 12 key indicators improved last year while only one declined. “We can be proud of the progress we have made. It demonstrates what can happen when government, businesses, and individuals work cooperatively,” wrote William C. Baker in the president’s message to the CFB’s 2012 State of the Bay report. “But we cannot rest. … There is a great deal left to do.”

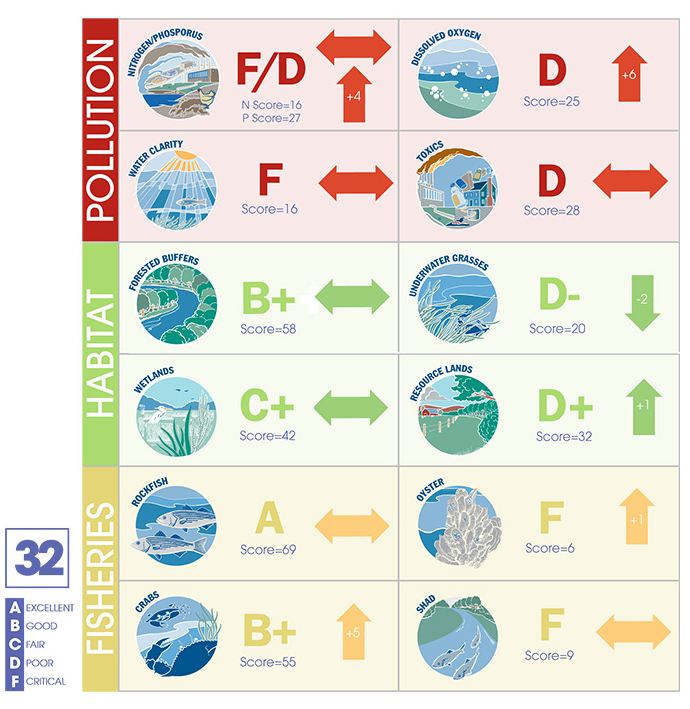

Pollution. Among pollution indicators, phosphorous loads declined and dissolved oxygen levels rose. Perhaps most encouraging was the fact that the average size of the Chesapeake’s dead zone (lacking sufficient oxygen to sustain life) was the second smallest since 1985. There was no change in nitrogen, water clarity or toxics from the previous year.

Pollution. Among pollution indicators, phosphorous loads declined and dissolved oxygen levels rose. Perhaps most encouraging was the fact that the average size of the Chesapeake’s dead zone (lacking sufficient oxygen to sustain life) was the second smallest since 1985. There was no change in nitrogen, water clarity or toxics from the previous year.

Habitat. Overall habitat scores declined slightly, with the deterioration of underwater grasses outweighing gains in resource lands. The acreage of underwater grasses, which create crucial habitat for many underwater species, had plunged 20% in 2011 and showed little improvement in 2012. The positive news is that major grass beds survived heavy rain events that bring deadly sediment runoff. On the positive side, Pennsylvania and Virginia have been converting significant acreage from farms to forests — 37,000 acres in Pennsylvania, 23,000 acres in Virginia — more than offsetting the loss of 8,000 acres in Maryland. Virginia also added 58,800 acres of protected resource lands, double the level of Pennsylvania and Maryland combined.

Fisheries. Blue crabs continued their comeback in 2012, reaching the highest winter survey since the mid-1990s. Oysters also appeared to turn a corner, thanks to a concerted restoration effort, although it may take several more years of scientific assessment to say that oysters are out of the woods (to use an entirely inappropriate metaphor). Indicators for shad and rockfish remained steady.

Looking ahead, the CFB report highlighted efforts to save menhaden, a foundational fish species upon which other fish and wildlife prey. Among other actions, Virginia is considering imposing a catch limit on the species. (See Don Rippert’s political analysis here.) Cattle-farming best practices, such as rotational grazing and fencing cattle out of local streams, are being implemented. And local governments are investing more in storm water management.

While state governments, local governments and businesses will need to invest billions of dollars more in the years to come, the CFB dangled the encouraging prospect that innovative technologies and creative approaches might reduce the price tag. States the report: “The projected costs are already dropping in many jurisdictions. For example, a year ago, Frederick County, Maryland, estimated reducing polluted runoff might cost $4.3 billion. That number dropped to $1.5 billion when the state provided information about approved techniques. We believe these costs will continue to decrease.”

Bacon’s bottom line: It hasn’t been easy summoning the political will to spend tens of billions of dollars on the Bay. But the financial sacrifice becomes easier to bear when we see the results. For many years the best that could be said, it seemed, was that the Bay was deteriorating more slowly. Now it’s actually healing. That knowledge bolsters our commitment to forge ahead.