The McDonnell administration has pushed through $200 million in funding for the Charlottesville Bypass over strenuous local opposition. The big question: Will the bypass need a bypass five years from now?

by James A. Bacon

The Commonwealth Transportation Board (CTB) voted today to provide $197 million in funding to build the 6-mile Charlottesville Bypass and another $33 million to widen a 1.6-mile stretch of U.S. 29. The controversial bypass project is almost certain to receive final approval in August by the Charlottesville-Albemarle Metropolitan Planning Organization.

The vote represents a significant victory for the McDonnell administration, which lobbied Republican board members on the Albemarle County Board of Supervisors earlier this month to reverse its previous opposition to the project, thus creating an opening for the CTB deliberation. After years of transportation funding cutbacks across Virginia, the Charlottesville Bypass is likely just the first in a series of mega-projects likely to receive funding as the administration dispenses the proceeds from $3 billion in transportation bond issues leveraged, in many instances, by public-private partnerships.

Ironically, the project received its strongest backing from CTB board members from outside the Charlottesville area, while James Rich, representing the Culpeper transportation district of which Albemarle County is a part, spoke passionately against it. Business and civic leaders in Lynchburg and Danville deem U.S. 29 to be an economic lifeline for the region’s manufacturing sector, and they regard the severe congestion north of Charlottesville as a hindrance to their economic development.

Opponents accused the administration of moving too fast, with too little transparency, in doling out the money. The Charlottesville Bypass will be funded at the expense of other more pressing projects. “Virginia has many transportation needs competing for limited money, and shifting these funds will shortchange other projects statewide,” said Trip Pollard with the Southern Environmental Law Center. “That’s not sound planning, especially when there are far more effective and less costly alternatives to reduce congestion.”

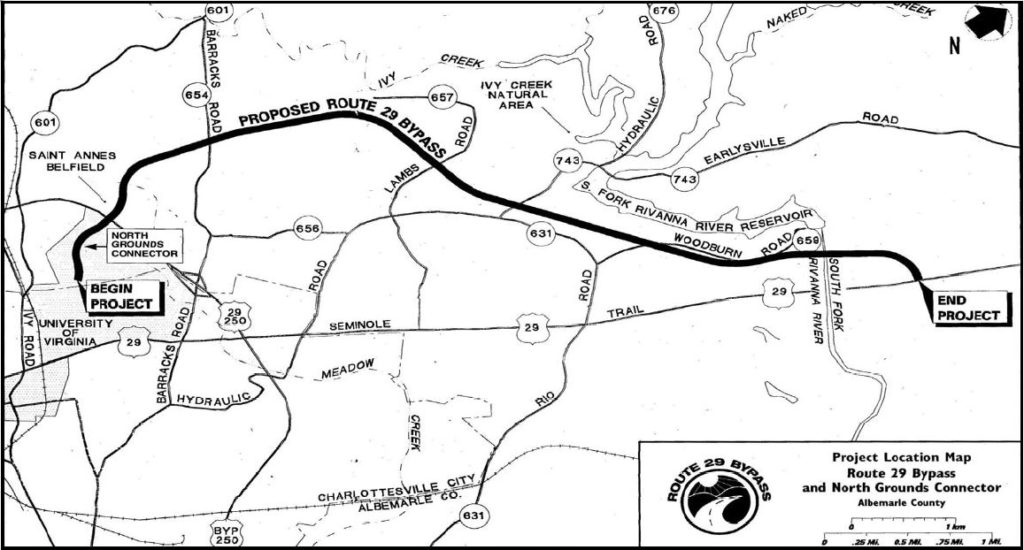

(Click on map for more legible image.)

(Click on map for more legible image.)

The controversy highlighted an irreconcilable contradiction that plagues many of Virginia’s transportation corridors. On the one hand, U.S. 29 is a classified as a “corridor of statewide significance,” meaning that it plays a role in providing connectivity between urban centers. It is also a U.S. highway stretching from Pensacola, Fla., to Baltimore, Md. One stretch between Danville and Greensboro, N.C., is touted as “future Interstate 785.” On the other hand, the highway doubles as the primary development corridor in Charlottesville-Albemarle County. It is the location of 20,000 jobs, most of the region’s retail business and its largest residential real estate developments, accounting for 40% of the region’s tax base. Peak traffic reaches roughly 50,000 cars per day.

The lack of access controls along the U.S. 29 corridor means that anyone can build a strip mall, subdivision, office park or even a single-family home and connect directly to the highway. That practice, combined with Albemarle County’s decades-long policy of making it the count’s major growth corridor, has created nightmarish congestion. As one of the Albemarle dissenters summed up the dilemma in the public hearing, “It is not possible for a road to function as a highway and a commercial main street.”

In voting to fund the Charlottesville Bypass, the CTB board made clear its policy preference for maintaining the system integrity of the state’s corridors of statewide significance. “No one project is the solution,” said Doug Koelemay, representative of the Northern Virginia transportation district. “We need to look at all projects as a whole. We’re trying to make a system work.”

“This has gone on too long,” said Lynchburg district representative Mark Peake, alluding to the on-again, off-again history of the Bypass. “This is a United States highway, not the City of Charlottesville’s main street. … We’ve studied this for 20 years. We have the money now. Let’s do it!”

Because U.S. 29 is classified as a U.S. highway, it must be approved by the Charlottesville-Albemarle Metropolitan Planning Organization, but that should prove to be a formality. Two of the five MPO board members are Albemarle County supervisors who voted to rescind the county’s previous objection to the Bypass. A third is a VDOT official who answers ultimately to the Secretary of Transportation.

The 6-mile Bypass will run from Rt. 250 in the south to just north of the Rivanna River, bypassing about a 3 ½-mile stretch of U.S. 29 with 14 traffic lights. In a 1997 study, traffic was forecast to reach 24,400 vehicles per day by 2022, said James Utterback, Culpeper district administrator for the Virginia Department of Transportation. Utterback offered no estimate of how much travel time the Bypass would save.

Although there is a broad consensus that the $33 million allocated to widening a section of U.S. 29 is worthwhile, foes predicted that the $197 million spent on the Bypass will be largely wasted. The “bypass” is not even a bypass, they argued. It’s better labeled a “connector,” for it circumvents only half of the congested area. The “bypass” will dump travelers onto U.S. 29 just past the Rivanna River, where they will encounter many more miles of stop-and-go traffic. In the years ahead, congestion will only worsen as development continues to crowd the highway as far north as Ruckersville in Greene County. “In another five years, we’ll need to build another road to bypass the bypass,” predicted Albemarle resident Denny King during the public hearing.