With the non-stop news coverage about the federal budget and debt-ceiling crisis, I’ve been thinking a lot about the Boomergeddon scenario I wrote about back in 2010. Since I predicted a financial collapse of the federal government within 15 to 20 years, a number of significant developments have occurred. Congress enacted Obamacare, President Obama managed to raise taxes on the Top 1% and partisan deadlock created the blunt expenditure-cutting tool of sequestration. Economic growth has continued at a steady but sub-par pace, and Quantitative Easing has pushed interest rates to almost zero percent.

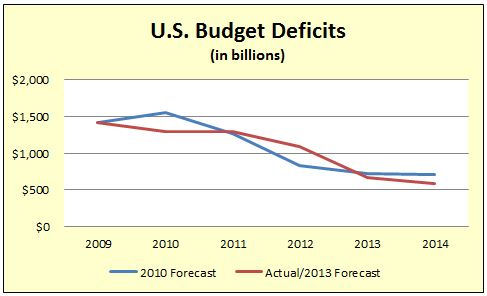

From a peak of $1,413 billion in 2009, the federal budget deficit has plummeted to $642 billion in 2013 — and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) forecasts that it could fall as low as $378 billion before embarking upon an rising again as more and more Boomers start drawing Social Security and Medicare.

Was I wrong to expect fiscal disaster? Are we, however noisily and messily, getting our budgetary house in order? I didn’t know the answer when I woke up this morning, so I checked the numbers.

As it turns out, I am no more optimistic than I was three years ago. The chart above tells part of the story. The blue line shows the deficit levels that the Obama administration was expecting back in 2010 when I was writing Boomergeddon. The red line shows the actual deficits (and CBO forecast for Fiscal 2013 and 2014). The numbers haven’t changed much.

The fact that the nation is on nearly the same fiscal trajectory as forecast back in 2010 is remarkable. Think about it. The tax increase on the rich has bolstered tax revenue. Sequestration has constrained spending. And Quantitative Easing has driven down the borrowing costs of government.

Indeed, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke deserves credit as the biggest deficit fighter in America. In 2010, the Obama administration anticipated that the country would be paying $510 billion in interest on the national debt in FY 2013. The actual figure: only $215 billion. That’s a $295 billion swing. In other words, roughly 40% of the deficit decline has occurred as a result of monetary stimulus, not fiscal discipline.

Given the higher taxes, reduced spending and monetary stimulus, why isn’t the deficit picture way better? One simple answer: Sub-par economic growth. Economic growth has consistently fallen short of Obama administration forecasts. Lower economic growth translates into lower-than-expected tax revenues and higher-than-expected transfer payments to the poor and unemployed.

So, the big question is this: Will economic growth resume traditional, post-World War II patterns? If so, there is hope. If not, we’re all toast.

On the positive side, the economy has worked its way through most of the damage caused by the 2007 real estate crash. Real estate prices are rising again, consumers are carrying far less indebtedness than they once did, and corporations have rock-solid balance sheets. We should be pulling out of the sluggish-recovery phase and entering the boom-boom phase of the business cycle. Over the longer haul, the economy should benefit from some promising trends — the U.S. energy boom, the re-shoring of American manufacturing and productivity gains from Big Data and the Internet of Things.

But we’re still mired in sub-par growth. The question of why will spark endless partisan disagreement. Democrats blame the uncertainty created by the Republican-caused debt and budget showdown. Republicans blame the Democratic-caused debt and budget showdown. The GOP attributes some of the economic languor to higher taxes on the wealth producers. Dems assert that the effect is negligible. The Donkey Clan implicates the slowdown in the global economy. The elephants indict the burden created by Obamacare, Wall Street regulatory “reform” and hundreds of smaller initiatives.

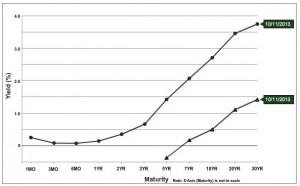

Here’s the 500-pound gorilla in the room: the $17 trillion debt. The graph to the left shows nominal interest rates and inflation-adjusted interest rates. Rates on U.S. debt with maturities of five years or less are negative on an inflation-adjusted basis. Even 30-year bonds are paying a real return of only 1.5%. If the U.S. is in slow-growth mode despite one of the most stimulative monetary regimes in its history, the prognosis is grim if interest rates ever move up.

And higher rates are almost inevitable. As soon as economic growth resumes and demand for credit increases, interest rates will rebound. The upward move will be accentuated by Federal Reserve Board promises to back off Quantitative Easement when job creation picks up. Indeed, interest rates shot up this summer when Bernanke merely hinted that he would gently decelerate the bond buying. Investors are hyper-vigilant and ready to unload their bonds at moment’s notice.

We face a predicament in which any sign of economic growth will trigger a rapid increase in interest rates, in effect capping the speed at which the economy can expand. The $17 trillion national debt will exert a severe drag on the economy for years, perhaps generations, to come. I don’t see any painless way out of the fix we have created for ourselves. We can stagger onward like this for another decade and a half, perhaps, but not much longer. I’ve been wrong before, and I could be wrong now. I hope I am. I truly dread the future that I see.